Chapter: Modern Medical Toxicology: Neurotoxic Poisons: Stimulants

Amphetamines - Stimulant Neurotoxic Poisons

Amphetamines

The

original amphetamine, racemic beta-phenylisopropylamine was first synthesised

in 1887, and was marketed in 1932 as a nasal decongestant (Benzedrine inhaler). Widespread abuse led to its ban in 1959.

Source

·

Amphetamine belongs to the phenylethylamine

family with a methyl group substitution in the alpha carbon position. Numerous

substitutions of the phenylethylamine struc-ture are possible, resulting in

several amphetamine-like compounds. These compounds have now collectively come

to be known as “amphetamines”, and include ampheta- mine phosphate, amphetamine

sulfate, benzphetamine, chlorphentermine, clobenzorex hydrochloride, dextroam-

phetamine, diethylpropion, mazindol, methamphetamine, 4-methylthioamphetamine,

methylphenidate, pemoline, phendimetrazine, phenmetrazine, and phentermine.

·

Methamphetamine abuse began in the

1950s and reached a peak in the 1970s. It used to be referred to as “speed” or

“go” (Fig 16.1). In the late 1980s,

a pure preparation of methamphetamine hydrochloride made its appearance for the

first time in Hawaii where it was referred to as “batu”. It quickly made its

way across to the United Kingdom, Australia, Western Europe, and USA, where it

became popular by the slang name “ice” (or “glass”) (Fig 16.2). While ice is produced by the ephedrine reduction method

and is very pure, occurring as large translucent crystals, a variant produced

by an oil-based method is called “crystal” (or “crank”), and is a white to

yellow crystal product.

·

Methamphetamine powder can be inhaled,

smoked, ingested,or injected. Ice and crystal are almost always smoked.

Uses

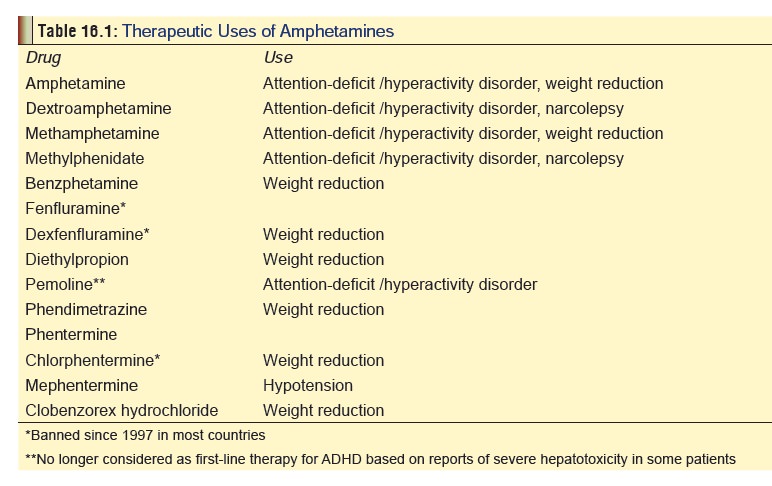

Some amphetamines have therapeutic uses and are still available as prescription drugs in Western countries (Table 16.1). They are not available in India (except for mephentermine).

Mode of Action

· The major mechanism of acion of amphetamines involves the release of monoamines from storage sites in axon termi-nals, which leads to increased monoamine concentration in the synaptic cleft. The release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and related structures is responsible for the reinforcing and mood elevating effects of amphetamines.

·

Methylphenidate has a different mechanism of action. Like

cocaine, it produces CNS action by blocking the dopamine transporters

responsible for the reuptake of dopamine from synapses following its release.

The relatively low abuse potential of orally administered methylphenidate is

due to slow occupation of dopamine transporters in the brain. Also, unlike

cocaine, methylphenidate occupies the transporter sites for a much longer time.

·

The most prominent effects of amphetamines are the

catecholamine effects as a result of stimulation of peripheral alpha and beta

adrenergic receptors. Enhanced concentra- tion of noradrenaline at the locus

coeruleus is responsible for the anorexic and stimulating effects, as well as

to some extent, for the motor-stimulating effects.

·

Cardiovascular effects result from the stimulation of

release of noradrenaline.

Toxicokinetics

·

In general, peak plasma levels are seen in about 30 minutes

after intravenous or intramuscular injection, and about 2 to 3 hours after oral

amphetamine ingestion.

·

Amphetamines are extensively metabolised in the liver, but

much of what is ingested is excreted unchanged in the urine. The excretion

of unchanged amphetamine is dependent on pH, and at urine pH less than 6.6, a

range of 67 to 73% of unchanged drug is excreted in the urine. At urine pH

greater than 6.7, the percent excreted unchanged in the urine is reported to be

17 to 43%.

Clinical Features

Acute Poisoning:

a. CNS:

·

Euphoria

·

Agitation

·

Headache

·

Paranoia

·

Anorexia

·

Hyperthermia: can be

severe, and may result from hypothalamic dysfunction, metabolic and muscle

hyperactivity, or prolonged seizures.

·

Hyperreflexia

·

Choreoathetoid

movements

·

Convulsions: Seizures

are associated with a high mortality rate

·

Intracerebral haemorrhage: Abuse of amphetamine and related

drugs can increase the risk for cerebro-vascular incidents in young adults

·

Coma: If it occurs,

is associated with a high mortality rate.

b. CVS

·

– Tachycardia: Tachycardia is common, however, reflex

bradycardia secondary to hypertension can occur.

·

–– Hypertension:

Hypertension is common following amphetamine use and may result in end organ

damage. Pulmonary hypertension has been associ-ated with methamphetamine use.

Hypotension and cardiovascular collapse may result from severe toxicity, and is

associated with a high fatality rate.

·

–– Arrhythmias.

·

–– Vasospasm.

·

–– Myocardial ischaemia: Infarction can occur (videinfra).

·

–– Cardiomyopathy: Acute and chronic cardiomyo-pathy can

result from hypertension, necrosis, or ischaemia.

c. Sympathetic

Effects:

·

Mydriasis

·

Sweating

·

Tremor

·

Tachypnoea

·

Nausea.

d. Other

Effects:

·

Muscle rigidity.

·

Pulmonary oedema.

·

Ischaemic colitis: More common in

chronic poisoning.

·

Rhabdomyolysis: Develops in patients

with severe agitation, muscular hyperactivity, hyperthermia, or seizures.

·

Metabolic acidosis: This occurs with

severe poisoning, and has even been reported after smoking crystal

methamphetamine.

e. Complications:

·

Psychosis with visual and tactile

hallucinations.

·

Cerebral infarction.

·

Myocardial infarction.

·

Aortic dissection: Several cases of

fatal aortic dissection associated with chronic amphetamine use have been

reported.

·

Ventricular fibrillation.

·

Acute renal failure: Renal failure

may develop secondary to dehydration or rhabdomyolysis in patients with severe

amphetamine poisoning.

·

Use of “ice” is associated with

unique neuropsy- chiatric toxicity. Auditory hallucinations, severe paranoia,

and violent behaviour have been reported.

·

Amphetamines and methamphetamines

can induce spontaneous recurrences of paranoid hallucinatory states known as

“flashbacks”.

Chronic Poisoning:

·

Amphetamines can be taken orally, by

injection, by absorption through nasal and buccal membranes; or by heating,

inhalation of the vapours, and absorption through the pulmonary alveoli.

Inhaled amphetamine is almost immediately absorbed with a rapid onset of

effects. Unlike cocaine, amphetamines can be vapour- ised without much

destruction of the molecule, thus obviating the need for preparing a free-base

form for smoking. As with opiates, the rapid onset of effects from amphetamine

injection or inhalation produces an intensely pleasurable sensation referred to

as “rush”.

·

Manifestations of heavy chronic

amphetamine use:

o Hyperactivity,

hyperexcitability.

o Anorexia,

loss of weight, emaciation: Weight loss is one of the most characteristic

findings with chronic use of amphetamine or its derivatives, and is said to be

the most striking effect in chronic “ice” smoking.

o Vomiting

and diarhoea are common. Ischaemic colitis may occur.

o Stereotyped

behaviour (skin picking, pacing, inter-

o minable

chattering).

o Dyskinesias:

bruxism, tics.

o Paranoid

psychosis, unpredictable violence: The most common symptoms in patients with

meth- amphetamine-induced psychosis were auditory and visual hallucinations,

persecutory delusions, and delusions of reference.

o Heightened

sexual activity initially, follo-wed by impotence and sexual dysfunction.

o Occasionally,

very rapid IV injection of a large dose produces a condition called

“overamped”, charac- terised by inability to speak or move even though

consciousness is fully retained. Blood pressure and temperature are usually

elevated. There may be respiratory distress.

o Deterioration

of social (family problems), physical (slovenly, unkempt appearance),

and economic (loss of job, bankruptcy)

status.

o Adverse

psychological reactions—anxiety reactions, amphetamine psychosis, exhaustion

syndrome, depression and hallucinosis.

·

Medical

complications—cardiomyopathy, vasculitis, pulmonary hypertension, permanent

neurological deficits, HIV infection, hepatitis, endocarditis, osteo- myelitis

and pulmonary abscesses.

·

Obstetric complications (in pregnant

users) — eclampsia, intrauterine growth retardation, prematurity,etc.

Amphetamine use during pregnancy has also been associated with birth defects, increased

risk of cardiac malformations and cleft palate.

·

Intravenous injection abusers may

display skin lesions, such as “tracks”, abscesses, ulcers, cellulitis, or

necro- tising angitis.

·

Withdrawal syndrome: Withdrawal

after prolonged amphetamine abuse may precipitate severe depres- sion and

suicide attempts. Anxiety, abdominal cramps, gastroenteritis, headache,

diaphoresis, leth- argy and dyspnoea may result. Increased appetite is common.

Drug Interactions

·

Sympathomimetics, monoamine oxidase

inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants cause potentiation of effects, while

antihistamines cause diminution of effects.

·

Amphetamines may increase

anticonvulsant levels.

Usual Fatal Dose

·

The fatal dose of amphetamines is

highly variable, and while death can occur with as little as 1.5 mg/kg of

metham- phetamine, survival has been recorded with 28 mg/kg. This in fact represents the usual range of

amphetamine’s lethal dose—150 mg to 2 grams. However, because of tolerance,

addicts can tolerate up to 5 grams (single IV dose), or 15 gm/day (smokable

methamphetamine).

·

Lethal blood level is said to be around 0.2 mg per 100 ml,

though addicts can tolerate much higher levels with hardly any toxic effects.

·

Death due to amphetamine toxicity most commonly results from

arrhythmias, hyperthermia, or intracerebral ![]() haemorrhage. In cases of survival, symptoms gradually

resolve as the drug is excreted over a period of 24 to 48 hours.

haemorrhage. In cases of survival, symptoms gradually

resolve as the drug is excreted over a period of 24 to 48 hours.

Diagnosis

· Urine is the specimen of choice.

Levels above 2 mg/100 ml indicate acute toxicity. Methods of analysis include

TLC,

·

RIA, HPLC, and GC-MS. The first three methods often give

false positive results, and hence confirmation of a positive test must always

be done by GC-MS.

· A new method (electron-impact mass

fragmentography) enables detection and even quantitation of methampheta-mine in

hair, nails, sweat, and saliva.

· Hair analysis may provide

documentation of methampheta-mine or other drug exposure for several months or

longer. To obtain hair samples, a new disposable scissors should be used to cut

a very small amount of hair (100 mg total, about the width of a pencil) from

about 10 different places. The hair must be cut as close to the scalp as

possible.

Treatment

Acute Poisoning:

Stabilisation:

·

i IV line, cardiac monitoring.

·

Oxygen.

·

Evaluate blood glucose, BUN, and electrolyte levels.

·

Consider the necessity of a CBC, urinalysis, coagu-lation

profile, chest X-ray, CT scan of head, and lumbar puncture, depending on the

presentation.

·

Measure core temperature.

·

Shock is a poor prognostic sign and needs to be managed

effectively. Consider the need for right-sided heart catheterisation to measure

right-sided filling pressure and cardiac output.

Supportive Measures:

·

Airway management, ventilatory support.

·

Rapid rehydration.

·

Mannitol diuresis promotes myoglobin clearance to prevent

renal failure.

·

Assess psychological and neurological status.

·

v Gastric decontamination (in cases of ingestion) with

appropriate tracheal protection. Activated charcoal is beneficial.

Specific Measures:

·

Anxiety, agitation, and hyperactivity can usually be

controlled with benzodiazepines. Diazepam is the drug of choice, and is

administered in a dose of 10 mg IV at intervals (up to a maximum of 100 mg).

Much larger doses (hundreds of milligrams) may be required to obtain adequate

sedation. Titrate dose to clinical response. Control of agitation is an

important aspect to the treatment of amphetamine overdose, since it often leads

to hyperthermia, a common cause of mortality in amphetamine overdose.

Neuroleptics are generally not preferred since they may aggravate hyperthermia,

convul-sions, and cardiac arrhythmias. Physical restraint is inadvisable, since

resistance against such measures will aggravate rhabdomyolysis and

hyperthermia. Extreme agitation and hallucinations may require the administration

of IV droperidol (up to 0.1 mg/kg). Since haloperidol lowers the seizures

threshold, and is associated with neuroleptic malig-nant syndrome, it is not

advisable.

·

Convulsions can be managed with benzodiaz-epines (IV

diazepam), phenytoin, or barbiturates. Refractory cases may require

curarisation.

·

Hyperthermia should be tackled aggressively with hypothermic

blankets, ice baths, and dantrolene infu-sions. Large IV doses of

benzodiazepines can help.

·

Refractory cases must be subjected to neuromuscular paralysis

and mechanical ventilation.

·

Tachycardia can be managed with beta blockers (atenolol).

Labetolol which has combined alpha and beta blocking effects, may be preferable

if tachycardia is associated with hypertension. Sedation with intra-venous

benzodiazepines (diazepam 5 to 10 mg IV repeated every 5 to 10 minutes as

needed) is usually sufficient for treating hypertension. A short acting,

titratable agent such as sodium nitroprusside should be considered if

unresponsive to benzodiazepines.

·

For ventricular arrhythmias: Lignocaine and amiodarone are

generally first line agents for stable monomorphic ventricular tachycardia.

Sotalol is a good alternative. Amiodarone and sotalol should be used with

caution if the QT interval is prolonged, or if torsades de pointes is involved

in the overdose.

·

Unstable rhythms require cardioversion. Atropine may be used

when severe bradycardia is present, and PVCs are thought to represent an escape

complex.

·

For rhabdomyolysis: Early aggressive fluid replacement is

the mainstay of therapy, and may help prevent renal insufficiency. Diuretics

such as mannitol or furosemide may be needed to maintain urine output. Urinary

alkalinisation is not routinely recommended.

·

Diazepam and chlorpromazine have been effective in treating

amphetamine-induced chorea.

·

Although peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis have been

demonstrated to enhance elimination of amphetamine, the clinical efficacy of

these procedures in human overdose has not been proven and they are rarely if

ever clinically indicated. Acidification of urine enhances amphetamine

excretion, but may precipitate acute renal failure in patients with

myoglobinuria and is therefore contraindicated.

Chronic Poisoning:

·

Most casual users of amphetamines do not need treat-ment.

Those with moderately severe dependence can be treated on an outpatient basis

without using drugs.

·

Strategies range from residential and ambulatory

detoxi-fication to day treatment, multistep activities, and case It is

preferable to provide a structured and manualised cognitive behavioural

treatment, making use of a combination of group and individual counselling.

·

A wide variety of pharmacological agents have been tried as

adjuncts to (or major elements in) the treatment of amphetamine dependence.

These include drugs such as imipramine and fluoxetine, but results have been

disappointing.

Related Topics