Chapter: Clinical Cases in Anesthesia : Ambulatory Surgery

What are the etiologies of nausea and vomiting, and what measures can be taken to decrease their incidence and severity?

What are the etiologies of

nausea and vomiting, and what measures can be taken to decrease their incidence

and severity?

Unfortunately, postoperative nausea and

vomiting remain a significant problem in patients who receive either general

anesthesia or intravenous sedation. They are among the most commonly reported

complications associated with ambulatory surgery, and hospitalization following

an ambulatory procedure is often attributable to them. Persistent and severe

retching or vomiting can disrupt sur-gical repairs and cause increased

bleeding; left untreated, they may lead to dehydration and electrolyte

imbalance. From 10% to 40% of patients who have not received anti-emetic prophylaxis

may be expected to experience some degree of nausea or frank vomiting. The

incidence of nausea and vomiting depends on the type of surgical proce-dure

performed, as well as the anesthetic administered. It has been demonstrated

that patients undergoing laparoscopy have a 35% incidence of nausea and

vomiting. This may be due to manipulation of abdominal viscera, retained

intraperitoneal carbon dioxide, and the use of electrocautery. Symptoms occur

regardless of whether a general anesthetic or epidural technique is employed.

Arthroscopic surgical procedures are associated with a much lower incidence of

symptoms than laparoscopic surgeries or ovum retrievals.

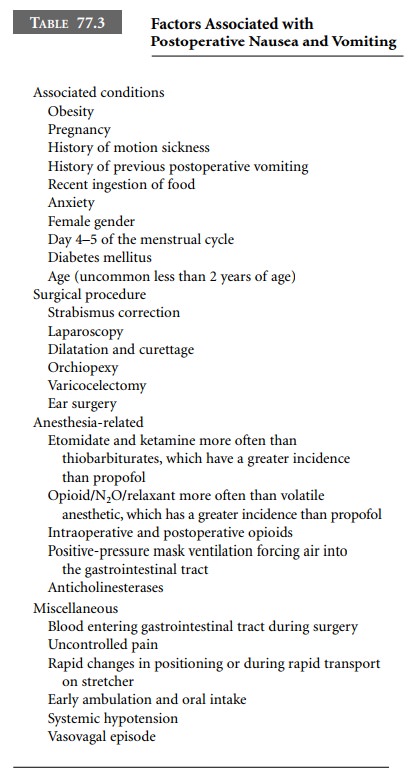

The cause of postoperative nausea and vomiting

is multifactorial (Table 77.3). Obesity, sudden movement or changes in patient

position, a history of motion sickness, postoperative hypotension, female

gender, days 4 and 5 of the menstrual cycle, pain, opioid administration, the

anes-thetic technique used, and site of surgery may all contribute to the

establishment and persistence of these symptoms. They are often disquieting and

sometimes incapacitating. Physical measures as well as pharmacologic agents

have been employed in an attempt to reduce the incidence of these distressing

sequelae. Examples include the attempted removal of stomach contents by

intraoperative gastric suc-tioning; avoidance of excessive positive pressure

during mask ventilation, which may force gas into the stomach; and diminished

use of opioid-based general anesthesia. These have proven to have variable

effects in the reduction of nausea and vomiting, probably because the problem

is strongly multifactorial in nature.

Nitrous oxide has been both implicated and

exonerated in multiple studies. It is unlikely that this gas plays a major role

in influencing the presence or absence of nausea in the postoperative period.

However, the selection of induction agent does influence the incidence of

postoperative symp-tomatology. Etomidate and ketamine are associated with a

much higher incidence of these symptoms when compared with thiopental. General

anesthesia induced and main-tained with propofol is associated with the least

number of episodes of nausea and emesis.

To help prevent symptoms, moving patients

slowly from the operating room table to the stretcher, avoiding sudden turns

during transport to the PACU, and allowing patients to wake up slowly have been

applied with some measure of success. Warm blankets and repeated verbal

reassurance may reduce overall anxiety by increasing feelings of well-being and

a sense of security. A vigorous stir-up, sit-them-up reg-imen with early oral

intake is likely to precipitate nausea and vomiting. The end result of

significant symptomatology is an increased length of stay in the PACU. For the

patient with unremitting symptoms, overnight admission for observation and

further treatment with anti-emetics and intravenous fluids to prevent

dehydration may be required.

Adequate hydration must be ensured during the

opera-tive period as well as maintained in the PACU. To avoid pre-cipitating

episodes of nausea or vomiting postoperatively, it is recommended to hydrate

vigorously intraoperatively with at least 15–20 mL/kg of crystalloid solutions

and to avoid pushing oral fluids and food. Intravenous fluid repletion allows

oral fluids to be offered sparingly. Solids should be withheld until the

patient expresses hunger. In addition, postponing early ambulation may help to

reduce symptoms.

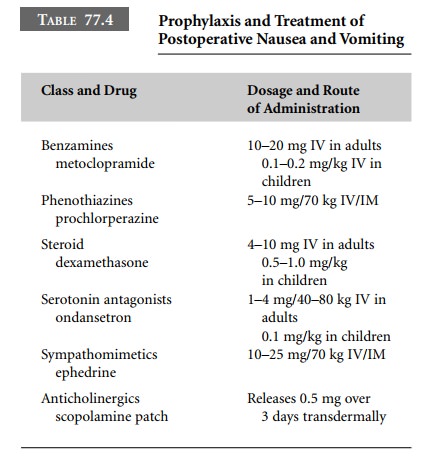

Prophylactic administration of dexamethasone

(4–10 mg IV) at the beginning of the procedure, and metoclopramide (10 mg IV)

have been advocated. Droperidol, a potent anti-emetic, has fallen into disfavor

because of its association with QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. This

led the FDA to issue a black-box warning regarding its use. The FDA’s

rec-ommendations have been challenged because of droperi-dol’s long history of

efficacy and rare occurrence of adverse events. If one decides to administer

droperidol, a baseline ECG should be performed, and the QT interval should be

measured. Furthermore, the ECG should be monitored during its administration

(Table 77.4).

Unfortunately, clinically significant

side-effects have been reported with these agents. These include prolonged

sedation and delayed awakening, an increase in anxiety as well as restlessness,

and extrapyramidal symptoms. Acute dystonic reactions including torticollis,

tics, or an oculogyric crisis can be treated with diphenhydramine, 25–50 mg, or

with benztropine, 1–2 mg, intravenously or intramuscularly.

Transdermal scopolamine, proven earlier to be

effica-cious in the prevention of motion sickness, has been studied for the

prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Although effective in reducing

symptoms when applied 12 hours before surgery, significant side-effects

including dry mouth as well as sedation, dysphoria, and urinary retention may

occur. It is often reserved for preoperative use in patients who have a strong

history of motion sickness. In the pediatric age group, the incidence of visual

distur-bances and hallucinations after application of the patch is increased.

Some clinicians have placed the patch before discharge in patients whose nausea

has not completely resolved. However, the patch should be avoided in the geriatric

population, pregnant or lactating patients, and in patients with glaucoma.

Ephedrine has been used in the treatment of

nausea and vomiting in the PACU. Hypotension or documented postural hypotension

in the postoperative period is often due to an intravascular volume deficit and

should be ruled out. Treatment consists of crystalloid infusion to correct

hemo-dynamic instability. Ephedrine has been demonstrated to be useful in

patients whose symptoms are causally related to assuming the upright position.

Ephedrine, 0.5 mg/kg given intramuscularly, has been used in laparoscopy

patients with some success. Patients who received ephedrine also had lower

sedation scores, and no differences in mean arterial blood pressure were noted.

It may be indicated in other-wise healthy patients who have a history of motion

sickness or in those patients who experience dizziness, nausea, or vomiting

when attempting to ambulate in the postopera-tive period.

A popular drug in the anesthesiologist’s

armamen-tarium against nausea and vomiting, ondansetron, is a serotonin

receptor antagonist with possible central and peripheral sites of action. It

does not appear to affect awakening from general anesthesia and has no

extra-pyramidal effects or sedative qualities. Ondansetron appears to offer

improved control over both nausea and vomiting. The effective dose is 2–4 mg

intravenously and has a duration of action of up to 24 hours. An oral

for-mulation is also available. It has been demonstrated that a combination of

agents, perhaps in conjunction with propofol, will prove to be most efficacious

in the prophyl-axis of nausea and vomiting.

Many surgical centers have abandoned the

routine administration of prophylactic anti-emetics to every patient. However,

anti-emetic regimens should be admin-istered for specific surgical procedures,

such as strabismus repair or laparoscopic surgery, that are associated with an

extraordinarily high incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Sometimes simply relieving postoperative pain

may alleviate nausea. The use of acupuncture has been reported in some studies

to be effective, but its use is not wide-spread. A propofol-based anesthetic is

associated with fewer emetic symptoms, earlier ability to tolerate oral

ali-mentation, and shorter stays in the PACU when compared with induction with

a thiobarbiturate and maintenance with isoflurane. Unfortunately, despite

careful anes-thetic management including propofol and even prophyl-actic

medication, symptoms of nausea and vomiting in the postoperative period still

remain a problem.

Related Topics