Chapter: Psychology: Memory

Psychology: Storage

STORAGE

We’ve been focusing on the first

step involved in memory—namely memory acquisi-tion. Once a memory is acquired,

though, it must be held in storage—i.e., held in long-term memory until it’s

needed. The mental representation of this new information is referred to as the

memory trace—and, surprisingly, we know

relatively little about exactly how traces are lodged in the brain. At a

microscopic level: Presynaptic neurons can become more effective in sending

signals; postsynaptic neurons can become more sensitive to the signals they

receive; and new synapses can be created.

On a larger scale, evidence

suggests that the trace for a particular past experience is not recorded in a

single location within the brain. Instead, different aspects of an event are

likely to be stored in distinct brain regions—one region containing the visual

ele-ments of the episode, another containing a record of our emotional

reaction, a third area containing a record of our conceptual understanding of

the event, and so on (e.g., A. Damasio & H. Damasio, 1994). But, within

these broad outlines, we know very little about how the information content of

a memory is translated into a pattern of neural connections. Thus, to be blunt,

we are many decades away from the science-fiction notion of being able to

inspect the wiring of someone’s brain in order to discover what he remembers,

or being able to “inject” a memory into someone by a suitable rearrange-ment of

her neurons. (For a recent hint about exactly how a specific memory might be

encoded in the neurons, see Han et al., 2009.)

One fact about memory storage,

however, is well established: Memory traces aren’t created instantly. Instead,

a period of time is needed, after each new experience, for the record of that

experience to become established in memory. During that time, memory consolidation is taking place;

this is a process, spread over several hours, inwhich memories are transformed

from a transient and fragile status to a more perma-nent and robust state

(Hasselmo, 1999; McGaugh, 2000, 2003; Meeter & Murre, 2004; Wixted, 2004).

What exactly does consolidation

accomplish? Evidence suggests that this time period allows adjustments in

neural connections, so that a new pattern of communica-tion among neurons can

be created to represent the newly acquired memory. This process seems to require

the creation of new proteins, so it is disrupted by chemical manipulations that

block protein synthesis (H. Davis & Squire, 1984; Santini, Ge, Ren,

deOrtiz, & Quirk, 2004; Schafe, Nader, Blair, & LeDoux, 2001).

The importance of consolidation

is evident in the memory loss sometimes produced by head injuries.

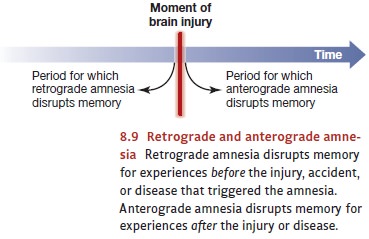

Specifically, people who have experienced blows to the head can develop retrograde amnesia (retrograde means “in a backward

direction”), in which they suffer a loss of memory for events that occurred before

the brain injury (Figure 8.9). This form of amnesia can also be caused by brain

tumors, diseases, or strokes (Cipolotti, 2001; M. Conway & Fthenaki, 1999;

Kapur, 1999;Mayes, 1988; Nadel & Moscovitch, 2001).

Retrograde amnesia

usually involves recent memories. In

fact, the older the memory, the less likely it is to be affected by the

amnesia—a pattern referred to as Ribot’s law, in honor of the 19th-century

scholar who first discussed

it (Ribot, 1882).

What produces this

pattern? Older memories have presumably had enough time to consolidate,

so they are less

vulnerable to disruption.

Newer memories are

not yet consolidated,

so they’re more liable to disruption (A. Brown, 2002; Weingartner &

Parker, 1984). There is, however, a complication here: Retrograde amnesia

sometimes disrupts a person’s

memory for events

that took place

months or even

years before the

brain injury. In these cases, interrupted consolidation

couldn’t explain the

deficit unlessone assumes—as some

authors do—that consolidation is an exceedingly long, drawn-out process. (For

discussion of when consolidation takes place, and how long it takes, see

Hupbach et al., 2008; McGaugh, 2000.) However, this issue remains a point of

debate, making it clear that we haven’t heard the last word on how

consoli-dation proceeds.

Related Topics