Chapter: Medical Physiology: Renal Regulation of Potassium, Calcium, Phosphate, and Magnesium; Integration of Renal Mechanisms for Control of Blood Volume and Extracellular Fluid Volume

Distribution of Extracellular Fluid Between the Interstitial Spaces and Vascular System

Distribution of Extracellular Fluid Between the Interstitial Spaces and Vascular System

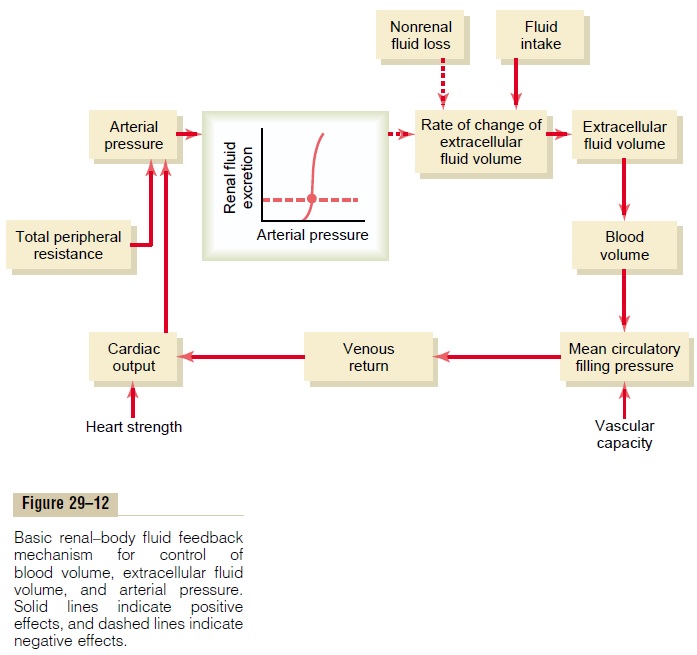

From Figure 29–12 it is apparent that blood volume and extracellular fluid volume are usually controlled in parallel with each other. Ingested fluid initially goes into the blood, but it rapidly becomes distributed between the interstitial spaces and the plasma. There-fore, blood volume and extracellular fluid volume usually are controlled simultaneously.

There are circumstances, however, in which the dis-tribution of extracellular fluid between the interstitial spaces and blood can vary greatly. As discussed, the principal factors that can cause accu-mulation of fluid in the interstitial spaces include (1) increased capillary hydrostatic pressure, (2) decreased plasma colloid osmotic pressure, (3) increased perme-ability of the capillaries, and (4) obstruction of lym-phatic vessels. In all these conditions, an unusually highproportion of the extracellular fluid becomes distrib-uted to the interstitial spaces.

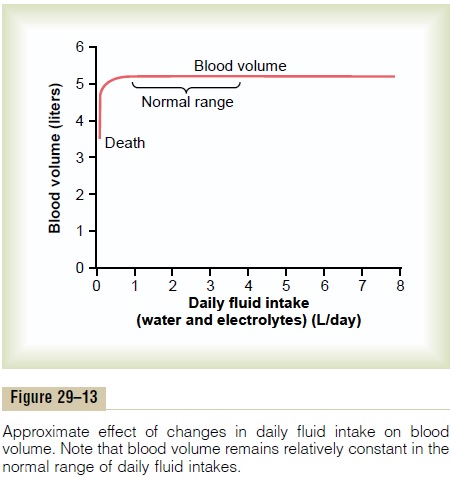

Figure 29–14 shows the normal distribution of fluid between the interstitial spaces and the vascular system and the distribution that occurs in edema states. When small amounts of fluid accumulate in the blood as a result of either too much fluid intake or a decrease in renal output of fluid, about 20 to 30 per cent of it stays in the blood and increases the blood volume. The remainder is distributed to the interstitial spaces. When the extracellular fluid volume rises more than 30 to 50 per cent above normal, almost all the addi-tional fluid goes into the interstitial spaces and little remains in the blood. This occurs because once the interstitial fluid pressure rises from its normally nega-tive value to become positive, the tissue interstitial spaces become compliant, and large amounts of fluid then pour into the tissues without interstitial fluid pressure rising much more. In other words, the safety factor against edema, owing to a rising interstitial fluid pressure that counteracts fluid accumulation in the tissues, is lost once the tissues become highly compliant.

Thus, under normal conditions, the interstitial spaces act as an “overflow” reservoir for excess fluid, sometimes increasing in volume 10 to 30 liters. This causes edema, but it also acts as an important overflow release valve for the cir-culation, protecting the cardiovascular system against dangerous overload that could lead to pulmonary edema and cardiac failure.

To summarize, extracellular fluid volume and blood volume are controlled simultaneously, but the quanti-tative amounts of fluid distribution between the interstitium and the blood depend on the physical properties of the circulation and the interstitial spaces as well as on the dynamics of fluid exchange through the capillary membranes.

Related Topics