Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment of Cardiovascular Function

Assessment of Cardiovascular Function: Physical Assessment

PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT

A

physical examination is performed to confirm the data obtained in the health

history. In addition to observing the patient’s gen-eral appearance, a cardiac

physical examination should include an evaluation of the following:

·

Effectiveness of the heart as a pump

·

Filling volumes and pressures

·

Cardiac output

·

Compensatory mechanisms

Indications

that the heart is not contracting sufficiently or functioning effectively as a

pump include reduced pulse pressure, cardiac enlargement, and murmurs and

gallop rhythms (abnor-mal heart sounds).

The

amount of blood filling the atria and ventricles and the re-sulting pressures

(called filling volumes and pressures) are esti-mated by the degree of jugular

vein distention and the presence or absence of congestion in the lungs,

peripheral edema, and postural changes in BP that occur when the individual

sits up or stands.

Cardiac

output is reflected by cognition, heart rate, pulse pres-sure, color and

texture of the skin, and urine output. Examples of compensatory mechanisms that

help maintain cardiac output are increased filling volumes and elevated heart

rate. Note that the findings on the physical examination are correlated with

data ob-tained from diagnostic procedures, such as hemodynamic moni-toring

(discussed later).

The

examination, which proceeds logically from head to toe, can be performed in

about 10 minutes with practice and covers the following areas: (1) general

appearance, (2) cognition, (3) skin, BP, (5) arterial pulses, (6) jugular

venous pulsations and pressures, (7) heart, (8) extremities, (9) lungs, and

(10) abdomen

General Appearance and Cognition

The

nurse observes the patient’s level of distress, level of conscious-ness, and

thought processes as an indication of the heart’s ability to propel oxygen to

the brain (cerebral perfusion). The nurse also observes for evidence of

anxiety, along with any effects emotional factors may have on cardiovascular

status. The nurse attempts to put the anxious patient at ease throughout the

examination.

Inspection of the Skin

Examination

of the skin begins during the evaluation of the gen-eral appearance of the

patient and continues throughout the as-sessment. It includes all body

surfaces, starting with the head and finishing with the lower extremities. Skin

color, temperature, and texture are assessed. The more common findings associated

with cardiovascular disease are as follows.

·

Pallor—a decrease in the color of

the skin—is caused by lack of oxyhemoglobin. It is a result of anemia or

decreased arterial perfusion. Pallor is best observed around the finger-nails,

lips, and oral mucosa. In patients with dark skin, the nurse observes the palms

of the hands and soles of the feet.

·

Peripheral cyanosis—a bluish tinge,

most often of the nails and skin of the nose, lips, earlobes, and

extremities—suggests decreased flow rate of blood to a particular area, which

allows more time for the hemoglobin molecule to become desatu-rated. This may

occur normally in peripheral vasoconstric-tion associated with a cold

environment, in patients with anxiety, or in disease states such as HF.

·

Central cyanosis—a bluish tinge

observed in the tongue and buccal mucosa—denotes serious cardiac disorders

(pulmonary edema and congenital heart disease) in which venous blood passes

through the pulmonary circulation without being oxygenated.

·

Xanthelasma—yellowish, slightly

raised plaques in the skin—may be observed along the nasal portion of one or

both eyelids and may indicate elevated cholesterol levels

(hypercholesterolemia).

·

Reduced skin turgor occurs with

dehydration and aging.

·

Temperature and moistness are controlled

by the auto-nomic nervous system. Normally the skin is warm and dry. Under

stress, the hands may become cool and moist. In car-diogenic shock, sympathetic

nervous system stimulation causes vasoconstriction, and the skin becomes cold

and clammy. During an acute MI, diaphoresis is common.

·

Ecchymosis (bruise)—a purplish-blue

color fading to green, yellow, or brown over time—is associated with blood

out-side of the blood vessels and is usually caused by trauma. Pa-tients who

are receiving anticoagulant therapy should be carefully observed for

unexplained ecchymosis. In these pa-tients, excessive bruising indicates

prolonged clotting times (prothrombin or partial thromboplastin time) caused by

an anticoagulant dosage that is too high.

·

Wounds, scars, and tissue

surrounding implanted devices should also be examined. Wounds are assessed for

adequate healing, and any scars from previous surgeries are noted. The skin

surrounding a pacemaker or implantable cardio-verter defibrillator generator is

examined for thinning, which could indicate erosion of the device through the

skin.

Blood Pressure

Systemic

arterial BP is the pressure exerted on the walls of the ar-teries during

ventricular systole and diastole. It is affected by fac-tors such as cardiac

output, distention of the arteries, and the volume, velocity, and viscosity of

the blood. BP usually is expressed as the ratio of the systolic pressure over

the diastolic pressure, with normal adult values ranging from 100/60 to 140/90

mm Hg. The average normal BP usually cited is 120/80 mm Hg. An in-crease in BP

above the upper normal range is called hypertension, whereas a decrease below

the lower range is called hypotension.

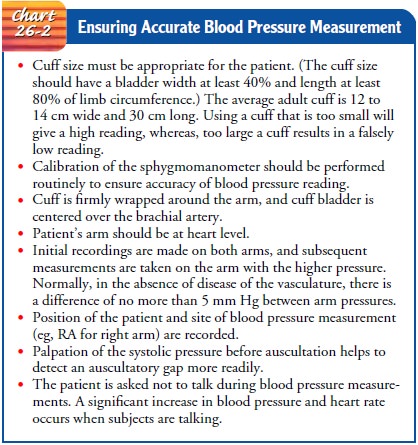

BLOOD PRESSURE MEASUREMENT

BP

can be measured with the use of invasive arterial monitoring systems (discussed

later) or noninvasively by a sphygmomanometer and stethoscope or by an

automated BP monitoring device. A de-tailed description of the procedure for

obtaining BP can be found in nursing skills textbooks, and specific

manufacturer’s instruc-tions review the proper use of the automated monitoring

devices. Several important details must be observed to ensure that BP

measurements are accurate; these are highlighted in Chart 26-2.

PULSE PRESSURE

The difference between the systolic and the diastolic pressures is called the pulse pressure. It is a reflection of stroke volume, ejection velocity, and systemic vascular resistance. Pulse pressure, which normally is 30 to 40 mm Hg, indicates how well the patient main-tains cardiac output. The pulse pressure increases in conditions that elevate the stroke volume (anxiety, exercise, bradycardia), reduce systemic vascular resistance (fever), or reduce distensibility of the arteries (atherosclerosis, aging, hypertension). Decreased pulse pres-sure is an abnormal condition reflecting reduced stroke volume and ejection velocity (shock, HF, hypovolemia, mitral regurgitation) or obstruction to blood flow during systole (mitral or aorticstenosis). A pulse pressure of less than 30 mm Hg signifies a serious reduction in cardiac output and requires further cardiovascular assessment.

POSTURAL BLOOD PRESSURE CHANGES

Postural (orthostatic) hypotension occurs

when the BP dropssignificantly after the patient assumes an upright posture. It

is usually accompanied by dizziness, lightheadedness, or syncope.

Although

there are many causes of postural hypotension, the three most common causes in

patients with cardiac problems are a reduced volume of fluid or blood in the

circulatory system (intra-vascular volume depletion, dehydration), inadequate

vasocon-strictor mechanisms, and insufficient autonomic effect on vascular

constriction. Postural changes in BP and an appropriate history help health

care providers differentiate among these causes. The following recommendations

are important when assessing pos-tural BP changes:

·

Position the patient supine and flat

(as symptoms permit) for 10 minutes before taking the initial BP and heart rate

measurements.

·

Check supine measurements before

checking upright mea-surements.

·

Do not remove the BP cuff between

position changes, but check to see that it is still correctly placed.

·

Assess postural BP changes with the

patient sitting on the edge of the bed with feet dangling and, if appropriate, with

the patient standing at the side of the bed.

·

Wait 1 to 3 minutes after each

postural change before mea-suring BP and heart rate.

·

Be alert for any signs or symptoms

of patient distress. If nec-essary, return the patient to a lying position

before com-pleting the test.

·

Record both heart rate and BP and

indicate the correspond-ing position (e.g., lying, sitting, standing) and any

signs or symptoms that accompany the postural change.

Normal

postural responses that occur when a person stands up or goes from a lying to a

sitting position include (1) a heart rate increase of 5 to 20 bpm above the

resting rate (to offset reduced stroke volume and maintain cardiac output); (2)

an unchanged systolic pressure, or a slight decrease of up to 10 mm Hg; and (3)

a slight increase of 5 mm Hg in diastolic pressure.

A

decrease in the amount of blood or fluid in the circulatory system should be

suspected after diuretic therapy or bleeding, when a postural change results in

an increased heart rate and either a decrease in systolic pressure by 15 mm Hg

or a drop in the diastolic pressure by 10 mm Hg. Vital signs alone do not

dif-ferentiate between a decrease in intravascular volume and in-adequate

constriction of the blood vessels as a cause of postural hypotension. With intravascular

volume depletion, the reflexes that maintain cardiac output (increased heart

rate and peripheral vasoconstriction) function correctly; the heart rate

increases, and the peripheral vessels constrict. However, because of lost

vol-ume, the BP falls. With inadequate vasoconstrictor mechanisms, the heart

rate again responds appropriately, but because of di-minished peripheral

vasoconstriction the BP drops. The follow-ing is an example of a postural BP

recording showing either intravascular volume depletion or inadequate

vasoconstrictor mechanisms:

Lying

down, BP 120/70, heart rate 70

Sitting,

BP 100/55, heart rate 90

Standing,

BP 98/52, heart rate 94

In

autonomic insufficiency, the heart rate is unable to increase to completely

compensate for the gravitational effects of an up-right posture. Peripheral

vasoconstriction may be absent or di-minished. Autonomic insufficiency does not

rule out a concurrent decrease in intravascular volume. The following is an

example of autonomic insufficiency as demonstrated by postural BP changes:

Lying

down, BP 150/90, heart rate 60

Sitting,

BP 100/60, heart rate 60

Arterial Pulses

Factors

to be evaluated in examining the pulse are rate, rhythm, quality, configuration

of the pulse wave, and quality of the arte-rial vessel.

PULSE RATE

The

normal pulse rate varies from a low of 50 bpm in healthy, athletic young adults

to rates well in excess of 100 bpm after ex-ercise or during times of

excitement. Anxiety frequently raises the pulse rate during the physical examination.

If the rate is higher than expected, it is appropriate to reassess it near the

end of the physical examination, when the patient may be more relaxed.

PULSE RHYTHM

The

rhythm of the pulse is as important to assess as the rate. Minor variations in regularity

of the pulse are normal. The pulse rate, particularly in young people,

increases during inhalation and slows during exhalation. This is called sinus

arrhythmia.

For

the initial cardiac examination, or if the pulse rhythm is irregular, the heart

rate should be counted by auscultating the apical pulse for a full minute while

simultaneously palpating the radial pulse.

Any

discrepancy between contractions heard and pulses felt is noted. Disturbances

of rhythm (dysrhythmias) often result in a pulse deficit, a difference between

the apical rate (the heart rate heard at the apex of the heart) and the

peripheral rate. Pulse deficits commonly occur with atrial fibrillation, atrial

flutter, premature ventricular contractions, and varying degrees of heart block.

To

understand the complexity of dysrhythmias that may be encountered during the

examination, the nurse needs to have a sophisticated knowledge of cardiac

electrophysiology, obtained through advanced education and training.

PULSE QUALITY

The

quality, or amplitude, of the pulse can be described as absent, diminished,

normal, or bounding. It should be assessed bilater-ally. Scales can be used to

rate the strength of the pulse. The fol-lowing is an example of a 0-to-4 scale:

0

pulse not palpable or absent

+1 weak, thready pulse; difficult to palpate;

obliterated with pressure

+2 diminished pulse; cannot be obliterated

+3 easy to palpate, full pulse; cannot be

obliterated

+4 strong, bounding pulse; may be abnormal

The

numerical classification is quite subjective; therefore, when documenting the

pulse quality, it helps to specify a scale range (eg, “left radial +3/+4”).

PULSE CONFIGURATION

The

configuration (contour) of the pulse conveys important in-formation. In

patients with stenosis of the aortic valve, the valve opening is narrowed,

reducing the amount of blood ejected into the aorta. The pulse pressure is

narrow, and the pulse feels feeble. In aortic insufficiency, the aortic valve

does not close completely, allowing blood to flow back or leak from the aorta

into the left ventricle. The rise of the pulse wave is abrupt and strong, and

its fall is precipitous—a “collapsing” or “water hammer” pulse. The true

configuration of the pulse is best appreciated by palpating over the carotid

artery rather than the distal radial artery, because the dramatic

characteristics of the pulse wave may be distorted when the pulse is

transmitted to smaller vessels.

EFFECT OF VESSEL QUALITY ON PULSE

The

condition of the vessel wall also influences the pulse and is of concern,

especially in older patients. Once rate and rhythm have been determined, the

nurse assesses the quality of the vessel by palpating along the radial artery

and comparing it with nor-mal vessels. Does the vessel wall appear to be

thickened? Is it tortuous?

To assess peripheral circulation, the

nurse locates and evalu-ates all arterial pulses. Arterial pulses are palpated

at points where the arteries are near the skin surface and are easily

compressed against bones or firm musculature. Pulses are detected over the

temporal, carotid, brachial, radial, femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and

posterior tibial arteries. A reliable assessment of the pulses of the lower

extremities depends on accurate identification of the location of the artery

and careful palpation of the area. Light palpation is essential; firm finger

pressure can easily oblit-erate the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses

and confuse the examiner. In approximately 10% of patients, the dorsalis pedis

pulses are not palpable. In such circumstances, both are usu-ally absent

together, and the posterior tibial arteries alone pro-vide adequate blood

supply to the feet. Arteries in the extremities are often palpated

simultaneously to facilitate comparison of quality.

Jugular Venous Pulsations

An

estimate of right-sided heart function can be made by observ-ing the pulsations

of the jugular veins of the neck. This provides a means of estimating central

venous pressure, which reflects right atrial or right ventricular end-diastolic

pressure (the pressure immediately preceding the contraction of the right

ventricle).

Pulsations

of the internal jugular veins are most commonly as-sessed. If they are

difficult to see, pulsations of the external jugu-lar veins may be noted. These

veins are more superficial and are visible just above the clavicles, adjacent

to the sternocleido-mastoid muscles. The external jugular veins are frequently

dis-tended while the patient lies supine on the examining table or bed. As the

patient’s head is elevated, the distention of the veins disappears. The veins

normally are not apparent if the head of the bed or examining table is elevated

more than 30 degrees.

Obvious

distention of the veins with the patient’s head elevated 45 degrees to 90

degrees indicates an abnormal increase in the vol-ume of the venous system.

This is associated with right-sided HF, less commonly with obstruction of blood

flow in the superior vena cava, and rarely with acute massive pulmonary

embolism.

Heart Inspection and Palpation

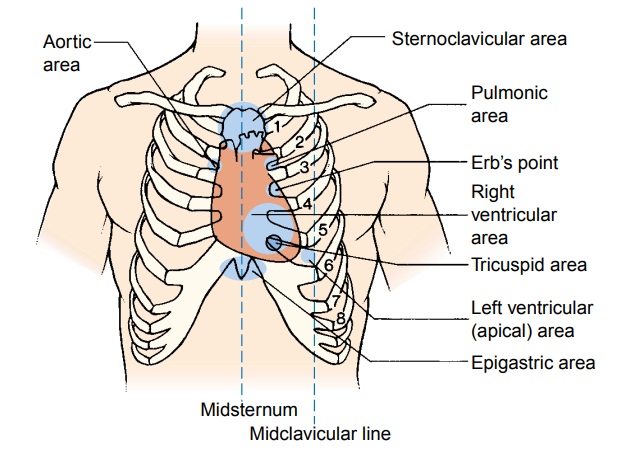

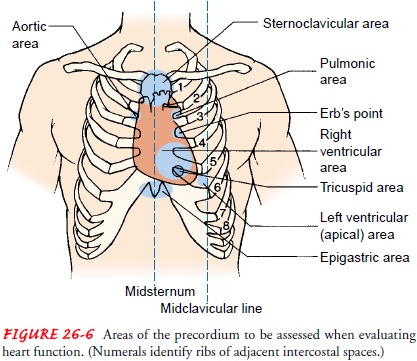

The

heart is examined indirectly by inspection, palpation, per-cussion, and

auscultation of the chest wall. A systematic approach is the cornerstone of a

thorough assessment. Examination of the chest wall is performed in the

following six areas (Fig. 26-6):

·

Aortic

area—second intercostal space to the right of thesternum. To

determine the correct intercostal space, start at the angle of Louis by

locating the bony ridge near the top of the sternum, at the junction of the

body and the manu-brium. From this angle, locate the second intercostal space

by sliding one finger to the left or right of the sternum. Subsequent

intercostal spaces are located from this refer-ence point by palpating down the

rib cage.

·

Pulmonic

area—second intercostal space to the left of thesternum

·

Erb’s

point—third intercostal space to the left of the sternum

·

Right

ventricular or tricuspid area—fourth and fifth inter-costal

spaces to the left of the sternum

·

Left

ventricular or apical area—the PMI, location on thechest where

heart contractions can be palpated

·

Epigastric

area—below the xiphoid process

For

most of the examination, the patient lies supine, with the head slightly

elevated. The right-handed examiner is positioned at the right side of the

patient and the left-handed examiner at the left side.

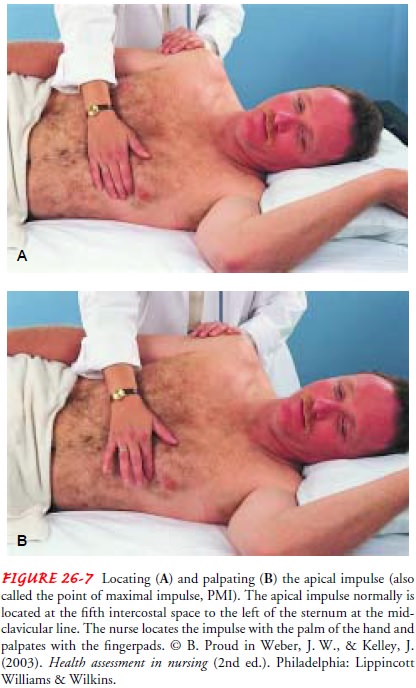

In

a systematic fashion, each area of the precordium is inspected and then

palpated. Oblique lighting is used to assist the examiner in identifying subtle

pulsation. A normal impulse that is distinct and located over the apex of the

heart is called the apical impulse

(PMI). It may be observed in young people and in older people who are thin. The

apical impulse is normally located and auscul-tated in the left fifth

intercostal space in the midclavicular line (Fig. 26-7).

In many cases, the apical impulse is palpable and is normally felt as a light pulsation, 1 to 2 cm in diameter. It is felt at the onset of the first heart sound and lasts for only half of systole. (See the next section for a discussion of heart sounds.) The nurse uses the palm of the hand to locate the apical impulse initially and the fingerpads to assess its size and quality. A broad and forceful apical impulse is known as a left ventricular heave or lift. It is so named because it appears to lift the hand from the chest wall during palpation.

An

apical impulse below the fifth intercostal space or lateral to the

midclavicular line usually denotes left ventricular enlarge-ment from left

ventricular failure. Normally, the apical impulse is palpable in only one

intercostal space; palpability in two or more adjacent intercostal spaces

indicates left ventricular enlargement. If the apical impulse can be palpated

in two distinctly separate areas and the pulsation movements are paradoxical

(not simulta-neous), a ventricular aneurysm should be suspected.

Abnormal,

turbulent blood flow within the heart may be pal-pated with the palm of the

hand as a purring sensation. This phe-nomenon is called a thrill and is

associated with a loud murmur. A thrill is always indicative of significant

pathology within the heart. Thrills also may be palpated over vessels when

blood flow is significantly and substantially obstructed and over the carotid

ar-teries if aortic stenosis is present or if the aortic valve is narrowed.

Chest Percussion

Normally,

only the left border of the heart can be detected by percussion. It extends

from the sternum to the midclavicular line in the third to fifth intercostal

spaces. The right border lies under the right margin of the sternum and is not

detectable. Enlarge-ment of the heart to either the left or right usually can

be noted. In people with thick chests, obesity, or emphysema, the heart may lie

so deep under the thoracic surface that not even its left border can be noted

unless the heart is enlarged. In such cases, unless the nurse detects a

displaced apical impulse and suspects cardiac en-largement, percussion is

omitted.

Related Topics