Chapter: Psychology: Prologue: What Is Psychology?

What Unites Psychology?

WHAT UNITES PSYCHOLOGY

?

It’s clear, then, that if we are

going to understand emotional memories—including why they are so vivid, why

they are sometimes inaccurate, why they can sometimes contribute to PTSD—we

need to study these memories from many perspectives and rely on many different

methods. And what holds true for these memories also holds true for most other

psychological phenomena. They too must be viewed from many perspectives because

each perspective is valid, and none is complete without the others.

With all this emphasis on

psychology’s diversity, though, both in the field’s content and in its

perspectives, what holds our field together? What gives the field its

coher-ence? The answer has two parts: a set of shared themes, and a commitment

to scientific methods.

A Shared Set of Thematic Concerns

As we have seen, psychologists

ask questions that require broad and complex answers. But, over and over, a

small number of themes emerge within these answers. These themes essentially

create a portrait of our science and are a central part of the answer to the

broad question “What has psychology learned?” These themes also highlight key

aspects of psychology’s subject matter

by highlighting crucial points about how the mind works and why we behave as we

do.

MULTIPLEP ERSPECTIVES

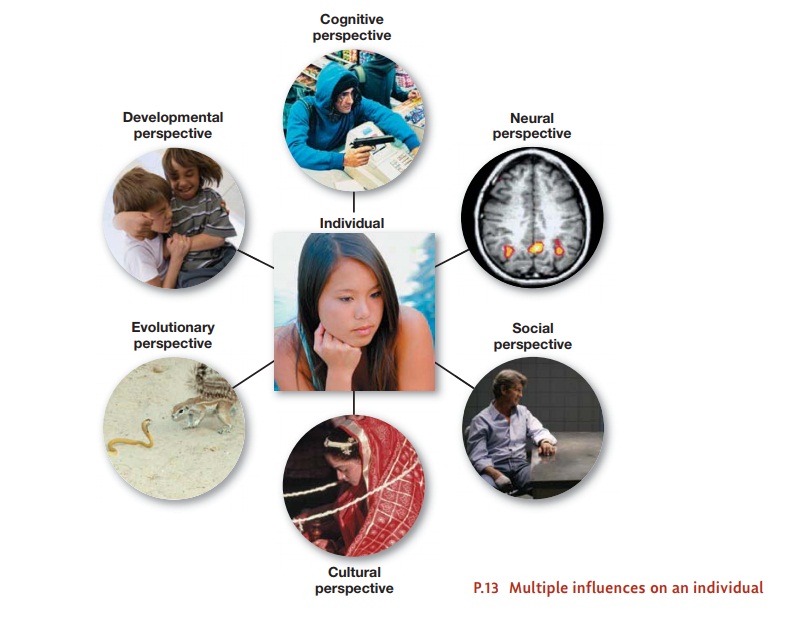

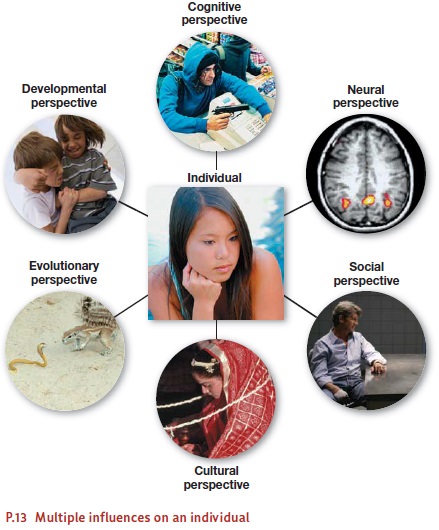

One of these recurrent themes has

already entered our discussion—namely, that the phenomena of interest to

psychology are influenced by many factors (Figure P.13). As we have seen, this

interaction among multiple factors forces the field to draw on a vari-ety of

perspectives, methods, and types of analysis. But, along with this

methodological point, there’s an important lesson here about the nature of the

mind, and the nature of behavior: We are complex organisms, sensitive to many

different cues and influences, and any theory that ignores this complexity will

inevitably be incomplete. This is, by the way, why the modern field of

psychology has largely stepped away from the all-inclusive

frameworks that once defined our

field—such as the framework proposed by Sigmund Freud, or the one proposed by

B. F. Skinner. The problem is not that these frameworks are wrong; indeed,

these scholars made enormous contributions to the field. The problem instead is

that each of these frameworks captures only part of the puzzle, and so our

explanations will ulti-mately need to draw on multiple types of explanation.

THE LIMITED VALUE OF DICHOTOMIES

Another theme is related to the

first: It concerns the interplay between our biologi-cal heritage, on the one

side, and the influence of our experiences, on the other. It’s sometimes easy

to think of these influences as separate. We might ask, for example, whether a

particular behavior is “innate” or “learned,” whether it is rooted in “nature”

or “nurture.” Similarly, it’s easy to ask whether a particular action arises

from inside the organism or is elicited by the environment; whether your

roommate acted the way she did yesterday because of her personality or because

of aspects of the situation. As our discussion of emotional memories has

indicated, though, these “either-or ” dichotomies often pose the issue in the

wrong way, as though we had to choose just one answer and dismiss the other.

The reality instead is that we need to consider nature and nurture, factors inside and

outside the organism. And—above all—we need to consider how these various

influences interact. Emotional memories, for example, are influenced by a rich

interaction between factors inside the organism (like our genetic heritage, or

the functioning of the amygdala, or the individual’s personality or prior

beliefs) and factors in the situa-tion (like cultural expectations, or

situational pressures). The same is true for most other behaviors as well.

WE ARE ACTIVE PERCEIVERS

A third theme has also already

come up in our discussion: We do not passively absorb our experience, simply

recording the sights and sounds we encounter. We have mentioned that our

memories integrate new experiences with prior knowledge, and that we seem to

“interpret as we go” in our daily lives and then store in memory the product of

this inter-pretation. These ideas, too, will emerge again and again in our

discussion, as we consider the active nature of the organism in selecting,

interpreting, and organizing experience.

THEI NEVITABILITY OF TRADE - OFFS

A fourth theme is related to the

third: Our activities, in interpreting our experience, both help us and hurt

us. They help by bringing us to a richer, deeper, better organized sense of our

experience, thus allowing us to make better use of that experience. But these

same activities can hurt us by leading to inaccuracy—if our interpretation is

off, or if our selection leads us to overlook or forget bits of the expe-rience

that we may need later. A similar kind of trade-off was relevant to our

discus-sion of PTSD: The biological mechanisms that promote emotional memory

ensure that we will remember the important events of our lives. But these same

mechanisms can burden us with memories that are more vivid and longer-lasting

than we might sometimes wish. Trade-offs like these, in which generally useful

mechanisms some-times have undesirable consequences, are evident throughout the

study of psychology. In other words, we’ll see over and over that some of the

undesirable aspects of our perception, memory, emotions, and behavior may just

be the price we pay for mechanisms that, in a wide range of circumstances,

serve us very well.

Broad themes like these bring a

powerful coherence to the field of psychology, despite its diversity of

coverage and methods. As we’ll see, there are important consistencies in how we

behave and why we do what we do, and these consistencies provide linkages among

the various areas of psychology.

A Commitment to Scientific Methods

Along with this set of thematic

concerns, another factor also unifies our field: a com-mitment to a scientific psychology. To understand the

importance of this point, let’s bear in mind that the questions occupying

psychologists today have fascinated people for thousands of years. Novelists

and poets have plumbed the nature of human action in countless settings.

Playwrights have pondered romantic liaisons or the relationship between

generations. The ancient Greeks commented extensively on the proper way to rear

children, and philosophers, social activists, and many others have offered

their counsel regarding how we should live—how we should eliminate violence,

treat mental illness, and so forth.

Against this backdrop, what is

distinctive about psychology’s contribution to these issues? A large part of

the answer is that psychologists, no matter what their perspec-tive, work

within the broad framework of science—by formulating specific hypotheses that

are open to definitive testing and then taking the steps to test these

hypotheses. In this fashion, we can determine which proposals are well founded

and which are not, which bits of counsel are warranted and which are ill

advised. Then, when we are rea-sonably certain about which hypotheses are

correct, we can build from there—knowing that we are building on a firm base.

Scientific research methods have

served psychology well. We know a great deal about emotional memories, and why

we sometimes forget things, and how children develop, and why some people

suffer from schizophrenia, and much more. But what is the sci-entific method,

and how is it used within psychology? By exploring these methodological points,

we’ll see how psychologists develop their claims. We’ll also learn why these

claims must be taken seriously and how they can be used as a basis for

developing applications and procedures that can, in truth, make our world a

better place.

Related Topics