Chapter: Psychology: Prologue: What Is Psychology?

Prologue: What Is Psychology?

Prologue: What

Is Psychology?

Why do we do the things we do?

Why do we feel thethings we feel, or say the things we say? Why do we find one

person attractive and another person obnoxious? Why are some people happy most

of the time, while others seem morose? Why do some children behave properly, or

learn easily, while others do not?

Questions like these all fall

within the scope of psychology, a field defined as the scientific study of behaviour and mental processes. Psychology is

concerned with who eachof us is and how we came to be the way we are. The field

seeks to understand each person as an individual, but it also examines how we

act in groups, including how we treat each other and feel about each other.

Psychology is concerned with what all

humans have in common, but it also looks at how each of us differs from the

others in our species—in our beliefs, our personalities, and our capabilities.

And psycholo-gists don’t merely seek to understand

these various topics; they are also interested in change: how to help people become happier or better adjusted, how

to help childrenlearn more effectively, or how to help them get along better

with their peers.

This is a wide array of topics;

and, to address them all, psychologists examine a diverse set of phenomena—including

many that nonpsychologists don’t expect to find within our field! But we need

this diverse coverage if we are to understand the many aspects of our thoughts,

actions, and feelings; and, in this text, we’ll cover all of these points and more.

Studying other species is one way

that psychologists can address these ques-tions. It turns out that many

species—young chimpanzees, wolf pups, and even kittens—engage in activities

that look remarkably like human play (Figure P.5C). And, in many of these

species, we see clear differences between male and female play—the playful

activities of the young males are more physical, and contain more elements of

aggression, than the activities of females.

As these points suggest, there

are surely biological influences on our play activities— and, in particular,

biological roots for the sexual differentiation of play. More broadly, the

widespread occurrence of play raises interesting questions about what the

function of play might be, such that evolution favored playtime in so diverse a

set of species.

Social Behavior in Humans

Animal playtime shares many

features with human play, including the central fact that play behavior is

typically social, involving the

coordinated activities of multiple individ-uals. Social interactions of all

sorts are intensely interesting to psychologists: Why do we treat other people

the way we do? How do we interpret the behaviors of others around us? How is

our own behavior shaped by the social setting?

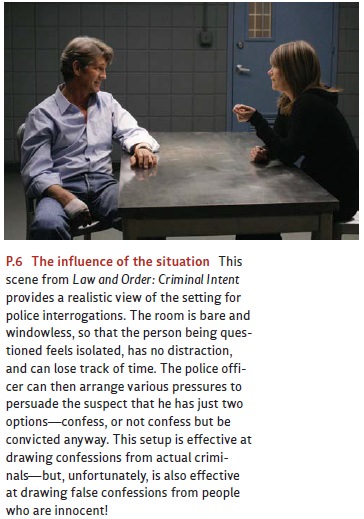

Many studies indicate, in fact,

that we are often powerfully influenced by the situations we find ourselves in.

One striking example concerns people who confess to crimes—including such

horrid offenses as murder or rape. Evidence from the laboratory as well as the

courts tells us that some of these confessions are false—meaning that people

are admitting to hideous actions they actually didn’t commit. In some cases,

the false confessions are the product of mental illness—they come from people who

have lost track of what is real and what is not, or people who have a

pathological need for attention. But in other cases, false confessions are

produced by the social situation that exists inside a police interrogation room

(Figure P.6): The suspect is confronted by a stern police officer who

steadfastly refuses the suspect’s claims of innocence. The suspect is also

isolated from any form of social

support—and so the interview continues for hours in a windowless room, where

the suspect has no contact with family or friends. The police officer controls

the flow of information about the crime, shaping the suspect’s beliefs about

the likelihood of being found guilty, and describing the probable consequences

of a conviction. With these factors in place, it’s surprisingly easy to extract

confessions from people who are, in truth, entirely innocent (Kassin &

Gudjonsson, 2004).

It should be said, though, that

the police in this setting are doing nothing wrong. After all, we do want

genuine criminals to confess; this will allow the efficient, accurate

prosecution of people who are guilty of crimes and deserve punishment. And, of

course, a criminal won’t confess in response to a polite request from the

police to “Please con-fess now.” Therefore, some pressure, some situational

control, is entirely appropriate when questioning suspects. It is troubling,

though, that the situational factors built into this questioning are so

powerful that they can elicit full confessions from people who have committed

no crime at all.

Related Topics