Chapter: Psychology: Prologue: What Is Psychology?

Cognitive Influences on Emotional Memory

Cognitive

Influences on Emotional Memory

It is clear, then, that our

understanding of emotional memory must include its biological basis—the neural

mechanisms that promote emotional memory, and the evolutionary heritage that

makes it easier for us to form some memories than oth-ers. But our theorizing

also needs to include the ways that people think

about the emotional events they experience: What do they pay attention to

during the experi-ence? How do they make sense of the emotional event, and how

does this interpre-tation shape their memory?

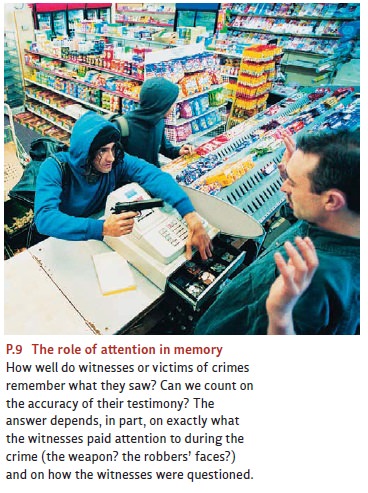

The role of attention is evident,

for example, in the fact that emotional memory tends to be uneven—some aspects

of the event are well remembered, other aspects are neglected. Thus, during a

robbery, witnesses might focus on the robbers themselves— what they did, what

they said (Figure P.9). As a result, the witnesses might remember these

“central” aspects of the event later on but might have little memory for other

aspects of the event—such as what the other witnesses were doing. In this

regard, memory is very different from, say, the sort of record created by a

videocamera. If the camera is turned on and functioning properly, it records

everything in front of the lens. Memory, in contrast, is selective; it records

the bits that someone was paying attention to, but nothing more. As a result,

memory—for emotional events and in general—is invariably incomplete. It can

sometimes omit information that is crucial for some purposes (e.g., information

the police might need when investigating the robbery).

Memory is also different from a

videorecord in another way. A video-camera is a passive device, simply

recording what is in front of the lens. In contrast, when you “record”

information into memory, you actively interpret the event, integrating

information gleaned from the event with other knowledge. Most of the time, this

is a good thing because it creates a rich and sophisticated memory trace that

preserves the event in combination with your impressions of the event as well

as links to other related episodes. However, this active interpretation of an

event also has a downside: People often lose track of the source of particular bits of information in memory. Specifically,

they lose track of which bits are drawn from the original episode they

experienced and which bits they supplied through their understanding of the

episode.

In one study, for example, people spent a few minutes in a profes-sor ’s office; then, immediately afterward, they were taken out of the office and asked to describe the room they had just been in. Roughly a third of these people clearly remembered seeing shelves full of books, even though no books were visible in the office (Brewer & Treyens, 1981). In this case, the participants had “supplemented” their memory of the office, relying on the common knowledge that professors’ offices usually do hold a lot of books. They then lost track of the source of this “sup-plement”—and so lost track of the fact that the books came from their own beliefs and not from this particular experience.

How does this pattern apply to

emotional memories? We have already said that emotional events tend to be

remembered vividly: Often, we feel like we can “relive” the distant event,

claiming that we recall the event “as though it were yesterday.” But as

compelling as they are, these memories—like any memories—are open to error. In

one study, researchers surveyed college students a few days after the tragic explosion

of the Space Shuttle Challenger in

1986. Where were the students when they heard about the explosion? Who brought

them the news? Three years later, the researchers questioned the same students

again. The students confidently reported that, of course, they clearly

remembered this horrible event. Many students reported that the memory was

still painful, and they could recall their sense of shock and sadness upon

hearing the news. Even so, their recollections of this event were, in many

cases, mis-taken. One student was certain she was sitting in her dorm room

watching TV when the news was announced; she recalled being deeply upset and

telephoning her par-ents. It turns out, though, that she had heard the news in

a religion class when some people walked into the classroom and started talking

about the explosion (Neisser & Harsh, 1992).

Similar results have been

recorded for many other events. For example, surveys of current college

students usually show that they vividly remember where they were when they

heard the news, of the September 11, 2001, attacks on the United States and how

they heard it. When we take steps to check on these memories, however, we often

find substantial errors. Many of the students are completely confident—but

mistaken— about how they learned of the attacks, who brought them the news,

what their initial responses were (e.g., P. Lee & Brown, 2004; Pezdek,

2004). Similar memory errors can be documented even in George W. Bush, U.S.

president at the time of the attacks (Figure P.10). Bush confidently recalled

where he was when he heard the news, and what he was doing at the time—but his

recollection turned out to be mistaken (D. Greenberg, 2004). Being president,

it seems, is no protection against memory errors.

What’s going on in all of these

cases? When we experience a trau-matic event—like the Challenger explosion, or the September 11 attacks—we’re likely to

focus on the core meaning of the event and pay less attention to our own

personal circumstances. This means that we will record into memory relatively

little information about those circumstances. Later, when we try to recall the

event, we’re forced to reconstruct the setting as best we can. This

reconstruction process is generally accurate, but certainly open to error. As a

result, our recollection of emotional events can be vivid, detailed,

compelling—and wrong.

Related Topics