Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Structural, Infectious, and Inflammatory Cardiac Disorders

Valvuloplasty

Valve Repair and Replacement Procedures

VALVULOPLASTY

The

repair, rather than replacement, of a cardiac valve is referred to as valvuloplasty. The type of

valvuloplasty depends on the cause and type of valve dysfunction. Repair may be

made to the commissures between the leaflets in a procedure known as com-missurotomy, to the annulus of the

valve by annuloplasty, to theleaflets, or to the chordae by chordoplasty.

Most

valvuloplasty procedures require general anesthesia and often require

cardiopulmonary bypass. Some procedures, how-ever, can be performed in the

cardiac catheterization laboratory; these procedures do not always require

general anesthesia or cardio-pulmonary bypass. Percutaneous partial cardiopulmonary

bypass is used in some cardiac catheterization laboratories. The

cardio-pulmonary bypass is achieved by inserting a large catheter (ie, cannula)

into two peripheral blood vessels, usually a femoral vein and an artery. Blood

is diverted from the body through the venous catheter to the cardiopulmonary

bypass machine and returned to the

patient through the arterial catheter.

The

patient is usually managed in a critical care unit for the first 24 to 72 hours

after surgery. Care focuses on hemodynamic stabilization and recovery from

anesthesia. Vital signs are assessed every 5 to 15 minutes and as needed until

the patient recovers from anesthesia or sedation and then every 2 to 4 hours

and as needed. Intravenous medications to increase or decrease blood pressure

and to treat dysrhythmias or altered heart rates are ad-ministered, and their

effects are monitored. The intravenous medications are gradually decreased

until they are no longer required or the patient takes needed medication by

another route (eg, oral, topical). Patient assessments are conducted every 1 to

4 hours and as needed, with particular attention to neurologic, respiratory,

and cardiovascular assessments.

After

the patient has recovered from anesthesia and sedation, is hemodynamically

stable without intravenous medications, and assessments are stable, the patient

is usually transferred to a telemetry or surgical unit for continued

postsurgical care and teaching. The nurse provides wound care and patient

teaching regarding diet, activity, medications, and self-care. Patients are

discharged from the hospital in 1 to 7 days. In general, valves that have

undergone valvuloplasty function longer than replace-ment valves, and the

patients do not require continuous anti-coagulation.

Commissurotomy

The

most common valvuloplasty procedure is commissurotomy. Each valve has leaflets;

the site where the leaflets meet is called the commissure. The leaflets may adhere to one another and close

thecommissure (ie, stenosis). Less commonly, the leaflets fuse in such a way

that, in addition to stenosis, the leaflets are also pre-vented from closing

completely, resulting in a backward flow of blood (ie, regurgitation). A

commissurotomy is the procedure performed to separate the fused leaflets.

CLOSED COMMISSUROTOMY

Closed

commissurotomies do not require cardiopulmonary by-pass. The valve is not

directly visualized. The patient receives a general anesthetic, a midsternal

incision is made, a small hole is cut into the heart, and the surgeon’s finger

or a dilator is used to break open the commissure. This type of commissurotomy

has been performed for mitral, aortic, tricuspid, and pulmonary valve disease.

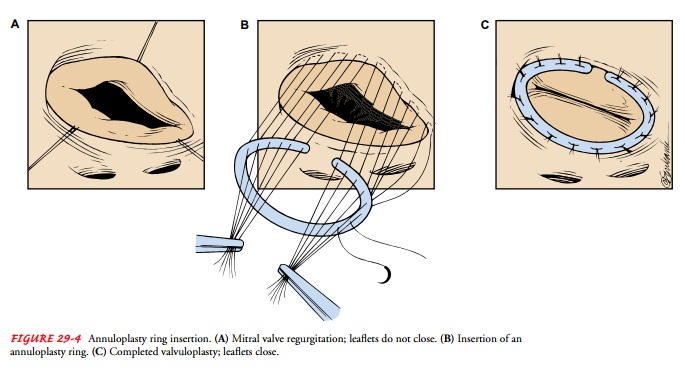

Balloon Valvuloplasty.

Balloon valvuloplasty (Fig. 29-3) is anothertype of closed

commissurotomy beneficial for mitral valve stenosis in younger patients, for

aortic valve stenosis in elderly patients, and for patients with complex

medical conditions that place them at high risk for the complications of more

extensive surgical proce-dures. Most commonly used for mitral and aortic valve

stenosis, balloon valvuloplasty also has been used for tricuspid and pulmonic

valve stenosis. The procedure is performed in the cardiac catheter-ization

laboratory, and the patient may receive a local anesthetic. Patients remain in

the hospital 24 to 48 hours after the procedure.

Mitral

valvuloplasty is contraindicated for patients with left atrial or ventricular

thrombus, severe aortic root dilation, signif-icant mitral valve regurgitation,

thoracolumbar scoliosis, rotation of the great vessels, and other cardiac

conditions that require open heart surgery.

Mitral balloon valvuloplasty involves advancing one or two catheters into the right atrium, through the atrial septum into the left atrium, across the mitral valve into the left ventricle, and out into the aorta. A guide wire is placed through each catheter, and the original catheter is removed. A large balloon catheter is then placed over the guide wire and positioned with the balloon across the mitral valve. The balloon is then inflated with a dilute angio-graphic solution. When two balloons are used, they are inflated simultaneously. The advantage of two balloons is that they are each smaller than the one large balloon often used, making smaller atrial septal defects. As the balloons are inflated, they usually do not completely occlude the mitral valve, thereby permitting some forward flow of blood during the inflation period.

All

patients have some degree of mitral regurgitation after the procedure. Other

possible complications include bleeding from the catheter insertion sites,

emboli resulting in complications such as strokes, and rarely, left-to-right

atrial shunts through an atrial septal defect caused by the procedure.

Aortic

balloon valvuloplasty also may be performed by passing the balloon or balloons

through the atrial septum, but it is per-formed more commonly by introducing a

catheter through the aorta, across the aortic valve, and into the left

ventricle. The one-balloon or the two-balloon technique can be used for

treating aortic stenosis. The aortic procedure is not as effective as the

pro-cedure for the mitral valve, and the rate of restenosis is nearly 50% in

the first 12 to 15 months after the procedure (Braunwald et al., 2001).

Possible complications include aortic regurgitation, emboli, ventricular

perforation, rupture of the aortic valve annulus, ven-tricular dysrhythmias,

mitral valve damage, and bleeding from the catheter insertion sites.

OPEN COMMISSUROTOMY

Open

commissurotomies are performed with direct visualization of the valve. The

patient is under general anesthesia, and a me-dian sternotomy or left thoracic

incision is made. Cardio-pulmonary bypass is initiated, and an incision is made

into the heart. A finger, scalpel, balloon, or dilator may be used to open the

commissures. An added advantage of direct visualization of the valve is that

thrombus may be identified and removed, calci-fications can be seen, and if the

valve has chordae or papillary muscles, they may be surgically repaired.

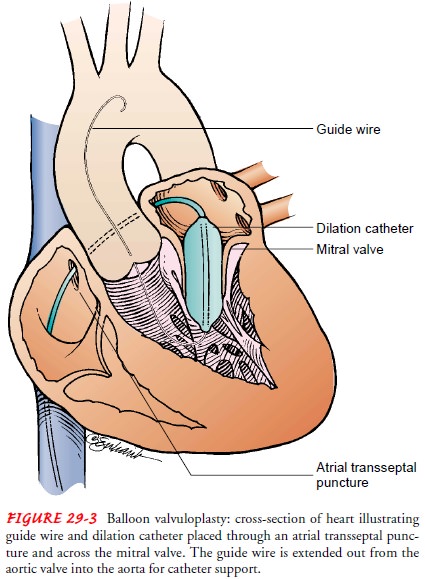

Annuloplasty

Annuloplasty is

the repair of the valve annulus (ie, junction ofthe valve leaflets and the

muscular heart wall). General anesthesia and cardiopulmonary bypass are

required for all annuloplasties. The procedure narrows the diameter of the

valve’s orifice and is useful for the treatment of valvular regurgitation.

There

are two annuloplasty techniques. One technique uses an annuloplasty ring (Fig.

29-4). The leaflets of the valve are sutured to a ring, creating an annulus of

the desired size. When the ring is in place, the tension created by the moving

blood and contracting heart is borne by the ring rather than by the valve or a

suture line, and progressive regurgitation is prevented by the repair. The

other technique involves tacking the valve leaflets to the atrium with su-tures

or taking tucks to tighten the annulus. Because the valve’s leaflets and the

suture lines are subjected to the direct forces of the blood and heart muscle

movement, the repair may degenerate more quickly than with the annuloplasty

ring technique.

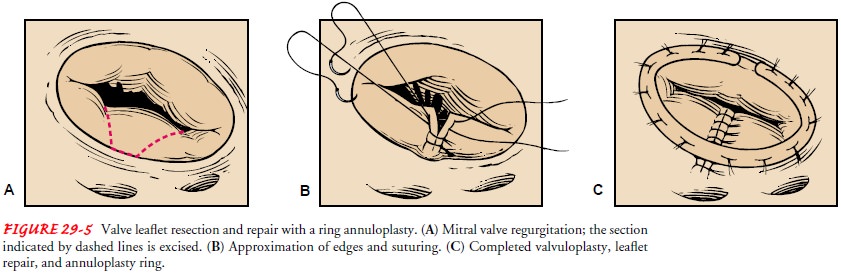

Leaflet Repair

Damage

to cardiac valve leaflets may result from stretching, short-ening, or tearing. Leaflet repair for elongated,

ballooning, or other excess tissue leaflets is removal of the extra tissue. The

elongated tissue may be folded over onto itself (ie, tucked) and sutured (ie,

leaflet plication). A wedge of tissue may be cut from the middle of the leaflet

and the gap sutured closed (ie., leaflet re-section) (Fig. 29-5). Short

leaflets are most often repaired by chordoplasty. After the short chordae are

released, the leaflets often unfurl and can resume their normal function of

closing the valve during systole. A piece of pericardium may also be sutured to

extend the leaflet. A pericardial patch may be used to repair holes in the

leaflets.

Chordoplasty

Chordoplasty is

the repair of the chordae tendineae. The mitralvalve is involved with

chordoplasty (because it has the chordae tendineae); seldom is chordoplasty

required for the tricuspid valve.

Regurgitation

may be caused by stretched, torn, or shortened chordae tendineae. Stretched

chordae tendineae can be shortened, torn ones can be reattached to the leaflet,

and shortened ones can be elongated. Regurgitation may also be caused by

stretched papillary muscles, which can be shortened.

Related Topics