Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Structural, Infectious, and Inflammatory Cardiac Disorders

Infective Endocarditis - Infectious Diseases of the Heart

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

Infective

endocarditis is an infection of the valves and endothe-lial surface of the

heart. Endocarditis usually develops in people with cardiac structural defects

(eg, valve disorders). Infective en-docarditis is more common in older people,

probably because of decreased immunologic response to infection and the

meta-bolic alterations associated with aging. There is a high incidence of

staphylococcal endocarditis among IV/injection drug users who most commonly

have infections of the right heart valves (Bayer et al., 1998; Braunwald,

2001).

The

incidence of infective endocarditis remained steady at about 4.2 cases per

100,000 patients in the years from 1950 to the mid-1980s (Braunwald et al.,

2001). The incidence then in-creased, partially attributed to increased

IV/injection drug abuse (Braunwald et al., 2001). In 1998, a total of 2212

deaths were attributed to infective endocarditis (American Heart Association,

2001). Invasive procedures, particularly those involving mucosal surfaces, can

cause a bacteremia. The bacteremia rarely lasts for more than 15 minutes

(Dajani et al., 1997). If a person has some anatomic cardiac defect, bacteremia

can cause bacterial endo-carditis (Dajani et al., 1997). The combination of the

invasive procedure, the particular bacteria introduced into the bloodstream,

and the cardiac defect may result in infective endocarditis.

Pathophysiology

Infective

endocarditis is most often caused by direct invasion of the endocardium by a

microbe (eg, streptococci, enterococci, pneumococci, staphylococci). The

infection usually causes de-formity of the valve leaflets, but it may affect

other cardiac structures such as the chordae tendineae. Other causative micro-organisms

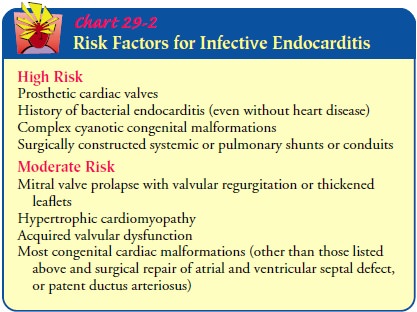

include fungi and rickettsiae. Patients at higher risk for infective

endocarditis are those with prosthetic heart valves, a his-tory of

endocarditis, complex cyanotic congenital malformations, and systemic or

pulmonary shunts or conduits that were surgically constructed (eg, saphenous

vein grafts, internal mammary artery grafts). At high risk are patients with

rheumatic heart disease or mitral valve prolapse and those who have prosthetic

heart valves (Chart 29-2).

Hospital-acquired endocarditis occurs most often in patients with debilitating disease, those with indwelling catheters, and those receiving prolonged intravenous or antibiotic therapy. Patients receiving immunosuppressive medications or cortico-steroids may develop fungal endocarditis.

A

diagnosis of acute infective endocarditis is made when the onset of infection

and resulting valvular destruction is rapid, oc-curring within days to weeks.

The onset of infection may take 2 weeks to months, diagnosed as subacute

infective endocarditis (Braunwald et al., 2001).

Clinical Manifestations

Usually,

the onset of infective endocarditis is insidious. The signs and symptoms

develop from the toxic effect of the infection, from destruction of the heart valves,

and from embolization of fragments of vegetative growths on the heart. The

occurrence of peripheral emboli is not experienced by patients with right heart

valve infective endocarditis (Bayer et al., 1998; Braunwald, 2001). The patient

exhibits signs and symptoms similar to those described in rheumatic

endocarditis (see previous discussion).

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

The

general manifestations, which may be mistaken for influenza, include vague

complaints of malaise, anorexia, weight loss, cough, and back and joint pain.

Fever is intermittent and may be absent in patients who are receiving

antibiotics or corticosteroids or in those who are elderly or have heart

failure or renal failure. Splinter hemorrhages (ie, reddish-brown lines and streaks)

may be seen under the fingernails and toenails, and petechiae may appear in the

conjunctiva and mucous membranes. Small, painful nodules (Osler’s nodes) may be

present in the pads of fingers or toes. Hemorrhages with pale centers (Roth’s

spots) that may be seen in the fundi of the eyes are caused by emboli in the

nerve fiber layer of the eye.

The

cardiac manifestations include heart murmurs, which may be absent initially.

Progressive changes in murmurs over time may be encountered and indicate

valvular damage from veg-etations or perforation of the valve or the chordae

tendineae. Enlargement of the heart or evidence of heart failure is also found.

The

central nervous system manifestations include headache, temporary or transient

cerebral ischemia, and strokes, which may be caused by emboli to the cerebral

arteries. Embolization may be a presenting symptom; it may occur at any time

and may involve other organ systems. Embolic phenomena may occur, as discussed

in the previous section on rheumatic endocarditis.

Although

the described characteristics may indicate infective endocarditis, the signs

and symptoms may indicate other diseasesas well. A definitive diagnosis is made

when a microorganism is found in two separate blood cultures, in a vegetation,

or in an ab-scess. Three sets of blood cultures (with each set including one

aerobic and one anaerobic culture) should be obtained before ad-ministration of

any antimicrobial agents. Negative blood cultures do not totally rule out the

diagnosis of infective endocarditis. An echocardiogram may assist in the

diagnosis by demonstrating a moving mass on the valve, prosthetic valve, or

supporting struc-tures and by identification of vegetations, abscesses, new

pros-thetic valve dehiscence, or new regurgitation (Braunwald et al., 2001). An

echocardiogram may also demonstrate the develop-ment of heart failure.

Prevention

Although

rare, bacterial endocarditis may be life-threatening. A key strategy is primary

prevention in high-risk patients (ie, those with rheumatic heart disease,

mitral valve prolapse, or prosthetic heart valves). Antibiotic prophylaxis is

recommended for high-risk patients immediately before and sometimes after the

following procedures:

·

Dental procedures that induce

gingival or mucosal bleed-ing, including professional cleaning and placement of

orthodontic bands (not brackets)

·

Tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy

·

Surgical procedures that involve

intestinal or respiratory mucosa

·

Bronchoscopy with a rigid

bronchoscope

·

Sclerotherapy for esophageal varices

·

Esophageal dilation

·

Gallbladder surgery

·

Cystoscopy

·

Urethral dilation

·

Urethral catheterization if urinary

tract infection is present

·

Urinary tract surgery if urinary

tract infection is present

·

Prostatic surgery

·

Incision and drainage of infected

tissue

·

Vaginal hysterectomy

·

Vaginal delivery

The

type of antibiotic used for prophylaxis varies with the type of procedure and

the degree of risk. The patient is usually in-structed to take 2 g of

amoxicillin (Amoxil) 1 hour before dental, oral, respiratory, or esophageal

procedures. If the patient is aller-gic to penicillin (eg, ampicillin [Omnipen,

Polycillin], carbenicillin [Geocillin], cloxacillin [Cloxapen], methicillin

[Staphcillin], nafcillin [Nafcil, Unipen], oxacillin [Prostaphlin, Bactocill],

penicillin G [Bicillin, Permapen]), clindamycin (Cleocin), ceph-alexin

(Keflex), cefadroxil (Duricef), azithromycin (Zithromax), or clarithromycin

(Biaxin) may be used. Recommendations for gastrointestinal or genitourinary

procedures are ampicillin and gentamicin (Garamycin) for high-risk patients,

amoxicillin or am-picillin for moderate-risk patients, and substituting

vancomycin (Vancocin) only for patients allergic to ampicillin or amoxicillin.

The

severity of oral inflammation and infection is a significant factor in the

incidence and degree of bacteremia. Poor dental hy-giene can lead to

bacteremia, particularly in the setting of a den-tal procedure. Regular

personal and professional oral health care and rinsing with an antiseptic

mouthwash for 30 seconds before dental procedures may assist in reducing the

risk of bacteremia. Increased vigilance is also needed in patients with

intravenous catheters. To minimize the risk of infection, nurses must ensure

that meticulous hand hygiene, site preparation, and the use ofaseptic technique

occur during the insertion and maintenance procedures (Schmid, 2000). All

catheters are removed as soon as they are no longer needed or no longer

function.

Complications

Even

if the patient responds to the therapy, endocarditis can be destructive to the

heart and other organs. Heart failure and cerebral vascular complications, such

as stroke, may occur before, during, or after therapy. The development of heart

failure, which may re-sult from perforation of a valve leaflet, rupture of

chordae, blood flow obstruction due to vegetations, or intracardiac shunts from

dehiscence of prosthetic valves, indicates a poor prognosis with medical

therapy alone and a higher surgical risk (Braunwald et al., 2001). Valvular

stenosis or regurgitation, myocardial damage, and mycotic (fungal) aneurysms

are potential heart complications. Many other organ complications can result

from septic or non-septic emboli, immunologic responses, abscess of the spleen,

mycotic aneurysms, and hemodynamic deterioration.

Medical Management

The

causative organism may be identified by serial blood cultures. The objective of

treatment is to eradicate the invading organism through adequate doses of an

appropriate antimicrobial agent.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Antibiotic

therapy is usually administered parenterally in a con-tinuous intravenous

infusion for 2 to 6 weeks. Parenteral therapy is administered in doses that

achieve a high serum concentration and for a significant duration to ensure

eradication of the dor-mant bacteria within the dense vegetations. This therapy

is often delivered in the patient’s home and is monitored by a home care nurse.

Serum levels of the selected antibiotic are monitored. If the serum does not

demonstrate bactericidal activity, increased dosages of the antibiotic are

prescribed, or a different antibiotic is used. Numerous antimicrobial regimens

are in use, but penicillin is usually the medication of choice. Blood cultures

are taken periodically to monitor the effect of therapy. In fungal endo-carditis,

an antifungal agent, such as amphotericin B (Abelect, Amphocin, Fungizone), is

the usual treatment.

The

patient’s temperature is monitored at regular intervals be-cause the course of

the fever is one indication of the effectiveness of treatment. However, febrile

reactions also may occur as a re-sult of medication. After adequate

antimicrobial therapy is ini-tiated, the infective organism usually disappears.

The patient should begin to feel better, regain an appetite, and have less

fa-tigue. During this time, patients require psychosocial support be-cause,

although they feel well, they may find themselves confined to the hospital or

home with restrictive intravenous therapy.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

After

the patient recovers from the infectious process, seriously damaged valves may

need to be replaced. Surgical valve replace-ment greatly improves the prognosis

for patients with severe symptoms from damaged heart valves. Aortic or mitral

valve ex-cision and replacement are required for patients who develop

congestive heart failure despite adequate medical treatment, pa-tients who have

more than one serious systemic embolic episode, and patients with uncontrolled

infection, recurrent infection, or fungal endocarditis. Many patients who have

prosthetic valve en-docarditis (ie, infected prostheses) require valve

replacement.

Nursing Management

The

nurse monitors the patient’s temperature; the patient may have fever for weeks.

Heart sounds are assessed; a new murmur may indicate involvement of the valve

leaflets. The nurse monitors for signs and symptoms of systemic embolization,

or for patients with right heart endocarditis, the nurse monitors for signs and

symptoms of pulmonary infarction and infiltrates. The nurse as-sesses signs and

symptoms of organ damage such as stroke (ie, cere-brovascular accident or brain

attack), meningitis, heart failure, myocardial infarction, glomerulonephritis,

and splenomegaly.

Patient

care is directed toward management of infection. The patient is started on

antibiotics as soon as blood cultures have been obtained. All invasive lines

and wounds should be assessed daily for redness, tenderness, warmth, swelling,

drainage, or other signs of infection. Patients and their families are

instructed about any activity restrictions, medications, and signs and symptoms

of infection. The nurse should instruct the patient and family about the need

for prophylactic antibiotics before, and possibly after, dental, respiratory,

gastrointestinal, or genitourinary procedures. Home care nurses supervise and

monitor intravenous antibiotic therapy delivered in the home setting and

educate the patient and family about prevention and health promotion. The nurse

pro-vides the patient and family with emotional support and facili-tates coping

strategies during the prolonged course of the infection and antibiotic

treatment required. If the patient received surgical treatment, the nurse

provides postoperative care and instruction.

Related Topics