Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Management of Patients With Structural, Infectious, and Inflammatory Cardiac Disorders

Rheumatic Endocarditis - Infectious Diseases of the Heart

Infectious Diseases of the Heart

Among

the most common infections of the heart are infective en-docarditis,

myocarditis, and pericarditis. The ideal management is prevention.

RHEUMATIC ENDOCARDITIS

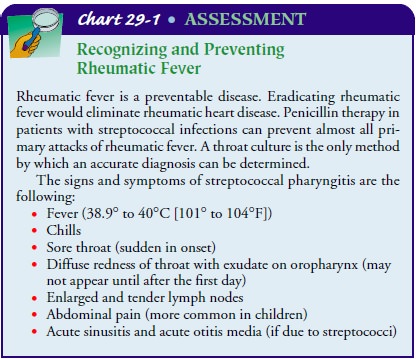

Acute rheumatic fever, which occurs most often in school-age children, follows 0.3% to 3% of cases of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis (Chin, 2001). Prompt treatment of strep throat with antibiotics can prevent the development of rheumatic fever (Chart 29-1). The Streptococcus is spread by direct contact with oral or respiratory secretions. Although the bacteria are the causative agents, malnutrition, overcrowding, and lower socioeconomic status may predispose individuals to rheumatic fever (Beers et al., 1999).

The incidence of rheumatic fever in the United States and other developed countries is believed to have steadily decreased, but the exact incidence is difficult to determine

because the infection may go unrecognized and patients may not seek treatment

(Braunwald et al., 2001; Beers et al., 1999). As many as 39% of patients with

rheumatic fever develop various degrees of rheumatic heart disease associated

with valvu-lar insufficiency, heart failure, and death (Chin, 2001). The

dis-ease also affects all bony joints, producing polyarthritis. The prevalence

of rheumatic heart disease is difficult to determine be-cause clinical

diagnostic criteria are not standardized and autop-sies are not routinely

performed. Except for rare outbreaks, the prevalence of rheumatic heart disease

in the United States is be-lieved to be less than 0.05 cases per 1000 people

(Chin, 2001). The number of U.S. citizens who die from rheumatic heart dis-ease

declined from approximately 15,000 in 1950 to about 4,000 in 2001 (AHA, 2001).

Pathophysiology

The

heart damage and the joint lesions of rheumatic endocardi-tis are not

infectious in the sense that these tissues are not invaded and directly damaged

by destructive organisms; rather, they rep-resent a sensitivity phenomenon or

reaction occurring in response to hemolytic streptococci. Leukocytes accumulate

in the affected tissues and form nodules, which eventually are replaced by scar

tis-sue. The myocardium is certain to be involved in this inflamma-tory

process; rheumatic myocarditis develops, which temporarily weakens the

contractile power of the heart. The pericardium also is affected, and rheumatic

pericarditis occurs during the acute illness. These myocardial and pericardial

complications usually occur without serious sequelae. Rheumatic endocarditis,

how-ever, results in permanent and often crippling side effects.

Clinical Manifestations

Rheumatic

endocarditis anatomically manifests first by tiny translucent vegetations or

growths, which resemble pinhead-sized beads arranged in a row along the free

margins of the valve flaps. These tiny beads look harmless enough and may

disappear with-out injuring the valve leaflets. More often, however, they have

serious effects. They are the starting point of a process that grad-ually

thickens the leaflets, rendering them shorter and thicker than normal and

preventing them from closing completely. The result is leakage, a condition

called valvular regurgitation. The

most common site of valvular regurgitation is the mitral valve. In some

patients, the inflamed margins of the valve leaflets become adherent, resulting

in valvular stenosis, a narrowed or stenotic valvular orifice. Regurgitation

and stenosis may occur in the same valve.

A

few patients with rheumatic fever become critically ill with intractable heart

failure, serious dysrhythmias, and pneumonia. These patients are treated in an

intensive care unit. Most patients recover quickly. However, although the

patient is free of symp-toms, certain permanent residual effects remain that

often lead to progressive valvular deformities. The extent of cardiac damage,

or even its existence, might not have been apparent in clinical ex-aminations

during the acute phase of the disease. Eventually, however, the heart murmurs

that are characteristic of valvular stenosis, regurgitation, or both become

audible on auscultation and, in some patients, even detectable as thrills on

palpation. Usually, the myocardium can compensate for these valvular de-fects

very well for a time. As long as the myocardium can com-pensate, the patient

remains in apparently good health. With continued valvular alterations, the

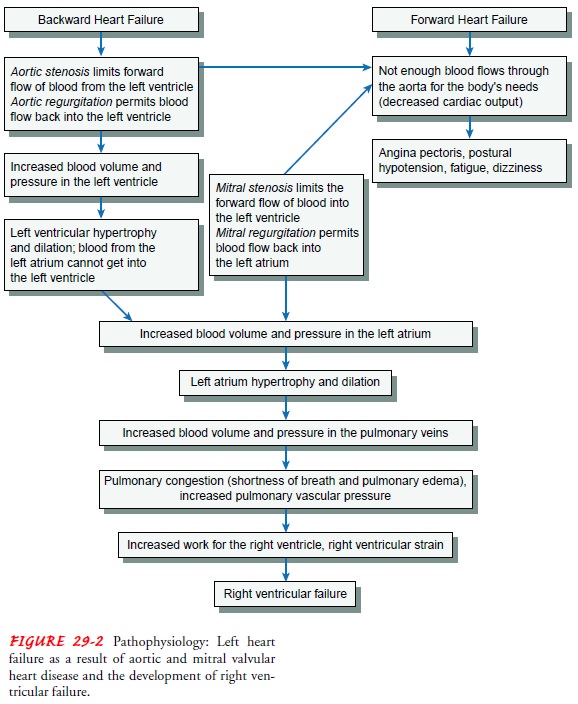

myocardium is unable to com-pensate (see Fig. 29-2), as evidenced by signs and

symptoms of heart failure.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

During

assessment, the nurse should keep in mind that the symp-toms depend on which

side of the heart is involved. The mitral valve is most often affected,

producing symptoms of left-sided heart failure: shortness of breath with

crackles and wheezes in the lungs. The severity of the symptoms depends on the

size and location of the lesion. The systemic symptoms that are pres-ent are

proportionate to the virulence of the invading organism. When a new murmur is

detected in a patient with a systemic in-fection, infectious endocarditis

should be suspected. The patient is also at risk for embolic phenomena of the lung

(eg, recurrent pneumonia, pulmonary abscesses), kidney (eg, hematuria, renal

failure), spleen (eg, left upper quadrant pain), heart (eg, myo-cardial

infarction), brain (eg, stroke), or peripheral vessels.

Prevention

Rheumatic

endocarditis is prevented through early and adequate treatment of streptococcal

infections. A first-line approach in preventing initial attacks of rheumatic

endocarditis is to recog-nize streptococcal infections, treat them adequately,

and control epidemics in the community. Every nurse should be familiar with the

signs and symptoms of streptococcal pharyngitis: high fever (38.9°C to 40°C [101°F to 104°F]),

chills, sore throat, redness of the throat with exudate, enlarged lymph nodes,

abdominal pain, and acute rhinitis.

Medical Management

The

objectives of medical management are to eradicate the causative organism and

prevent additional complications, such as a thromboembolic event. Long-term

antibiotic therapy is the recommended treatment, and penicillin administered

parenter-ally remains the medication of choice.

The

patient who has rheumatic endocarditis and whose valvu-lar dysfunction is mild

may require no further treatment. Never-theless, the danger exists for

recurrent attacks of acute rheumatic fever, bacterial endocarditis, embolism

from vegetations or mural thrombi in the heart, and eventual cardiac failure.

Nursing Management

A

key nursing role in rheumatic endocarditis is teaching patients about the

disease, its treatment, and the preventive steps needed to avoid potential

complications. After acute treatment with anti-biotics, patients need to learn

about the need to take prophylactic antibiotics before invasive procedures.

Related Topics