Chapter: Fundamentals of Database Systems : File Structures, Indexing, and Hashing : Indexing Structures for Files

Types of Single-Level Ordered Indexes

Types of Single-Level Ordered Indexes

The idea behind an ordered index is similar to that behind the index

used in a text-book, which lists important terms at the end of the book in

alphabetical order along with a list of page numbers where the term appears in

the book. We can search the book index for a certain term in the textbook to

find a list of addresses—page

numbers in this case—and use these addresses to locate the specified pages

first and then search for the term on

each specified page. The alternative, if no other guidance is given, would be to sift slowly through

the whole textbook word by word to find the term we are interested in; this

corresponds to doing a linear search,

which scans the whole file. Of course, most books do have additional

information, such as chapter and section titles, which help us find a term

without having to search through the whole book. However, the index is the only

exact indication of the pages where each term occurs in the book.

For a file with a given record structure consisting of several fields

(or attributes), an index access structure is usually defined on a single field

of a file, called an indexing field (or indexing attribute). The index typically stores each value of the index field along with a list of pointers to all disk blocks that

contain records with that field value. The values in the index are ordered so that we can do a binary search on the index. If both the

data file and the index file are ordered, and since the index file is typically

much smaller than the data file, searching the index using a binary search is a

better option. Tree-structured multilevel indexes (see Section 18.2) implement

an extension of the binary search idea that reduces the search space by 2-way

partitioning at each search step, thereby creating a more efficient approach

that divides the search space in the file n-ways

at each stage.

There are several types of ordered indexes. A primary index is specified on the ordering key field of an ordered file of records. Recall from Section 17.7 that an ordering key field is used to physically

order the file records on disk, and every record has a unique value for that field. If the ordering field is not a key

field—that is, if numerous records in the file can have the same value for the

ordering field— another type of index, called a clustering index, can be used. The data file is called a clustered file in this latter case.

Notice that a file can have at most one physical ordering field, so it can have at most one primary index or one

clustering index, but not both. A third type of index, called

a secondary index, can be specified on any nonordering field of a file. A data file can have several secondary

indexes in addition to its primary

access method. We discuss these types of single-level indexes in the next three

subsections.

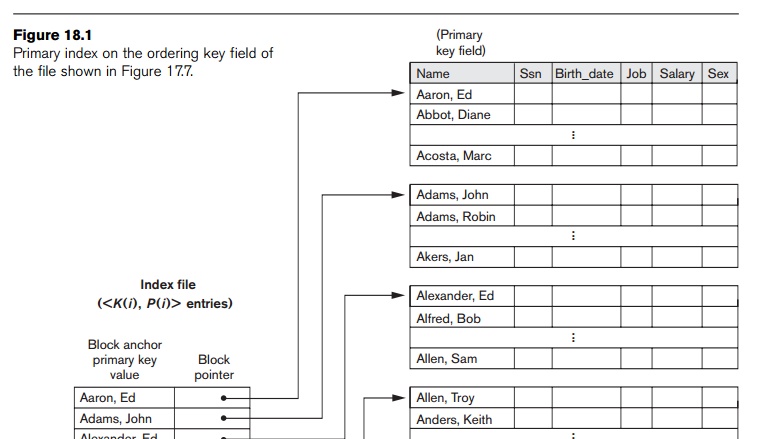

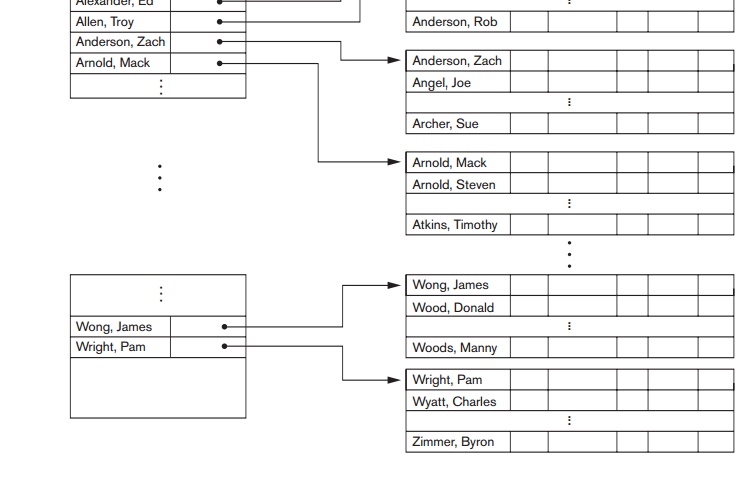

1. Primary Indexes

A primary index is an ordered file whose

records are of fixed length with two fields, and it acts like an access

structure to efficiently search for and access the data records in a data file.

The first field is of the same data type as the ordering key field—called the primary key—of the data file, and the

second field is a pointer to a disk block (a block address). There is one index entry (or index record) in the index file for each block in the data file. Each index entry has the value of the

primary key field for the first

record in a block and a pointer to that block as its two field values. We will

refer to the two field values of index entry i as <K(i), P(i)>.

To create

a primary index on the ordered file shown in Figure 17.7, we use the Name field as primary key, because

that is the ordering key field of the file (assuming that each value of Name is unique). Each entry in the

index has a Name value

and a pointer. The first three index entries are as follows:

<K(1) = (Aaron, Ed), P(1) = address of block 1>

<K(2) = (Adams, John), P(2) = address of block 2>

<K(3) = (Alexander, Ed), P(3) = address of block 3>

Figure

18.1 illustrates this primary index. The total number of entries in the index

is the same as the number of disk blocks

in the ordered data file. The first record in each block of the data file is

called the anchor record of the

block, or simply the block

anchor.2

Indexes

can also be characterized as dense or sparse. A dense index has an index entry for every search key value (and hence every record) in the data file. A

sparse (or nondense) index, on the

other hand, has index entries for only some of the search values. A sparse

index has fewer entries than the number of records in the file. Thus, a primary

index is a nondense (sparse) index, since it includes an entry for each disk

block of the data file and the keys of its anchor record rather than for every

search value (or every record).

The index

file for a primary index occupies a much smaller space than does the data file,

for two reasons. First, there are fewer

index entries than there are records in the data file. Second, each index

entry is typically smaller in size

than a data record because it has only two fields; consequently, more index

entries than data records can fit in one block. Therefore, a binary search on

the index file requires fewer block accesses than a binary search on the data

file. Referring to Table 17.2, note that the binary search for an ordered data

file required log2b block

accesses. But if the primary index file contains only bi blocks, then to locate a record with a search key

value

requires a binary search of that index and access to the block containing that

record: a total of log2bi

+ 1 accesses.

A record

whose primary key value is K lies in

the block whose address is P(i), where K(i) ≤ K < K(i

+ 1). The ith block in the data

file contains all such records because of

the physical ordering of the file records on the primary key field. To retrieve

a record, given the value K of its

primary key field, we do a binary search on the index file to find the

appropriate index entry i, and then

retrieve the data file block whose address is P(i).3 Example

1 illustrates the saving in block accesses that is attainable when a primary

index is used to search for a record.

Example 1. Suppose that we have an ordered

file with r

= 30,000

records stored on a disk

with block size B = 1024 bytes. File

records are of fixed size and are unspanned, with record length R = 100 bytes. The blocking factor for

the file would be bfr = (B/R)

= (1024/100) = 10 records per block. The number of blocks needed for the file

is b = (r/bfr) = (30000/10) =

3000 blocks. A binary search on the data file would need approximately log2b = (log23000) = 12 block

accesses.

Now

suppose that the ordering key field of the file is V = 9 bytes long, a block pointer is P = 6 bytes long, and we have constructed a primary index for the

file. The size of each index entry is Ri

= (9 + 6) = 15 bytes, so the blocking factor for the index is bfri = (B/Ri) = (1024/15) = 68 entries

per block. The total number of index entries ri is equal to the number of blocks in the data file,

which is 3000. The num-ber of index blocks is hence bi = (ri/bfri) = (3000/68) = 45

blocks. To perform a binary search on the index file would need (log2bi) = (log245) = 6

block accesses. To search for a record using the index, we need one additional

block access to the data file for a total of 6 + 1 = 7 block accesses—an

improvement over binary search on the data file, which required 12 disk block

accesses.

A major

problem with a primary index—as with any ordered file—is insertion and deletion

of records. With a primary index, the problem is compounded because if we

attempt to insert a record in its correct position in the data file, we must

not only move records to make space for the new record but also change some

index entries, since moving records will change the anchor records of some blocks. Using an unordered overflow file, as

discussed in Section 17.7, can reduce this problem. Another possibility is to

use a linked list of overflow records for each block in the data file. This is

similar to the method of dealing with overflow records described with hashing

in Section 17.8.2. Records within each block and its overflow linked list can

be sorted to improve retrieval time. Record deletion is handled using dele-tion

markers.

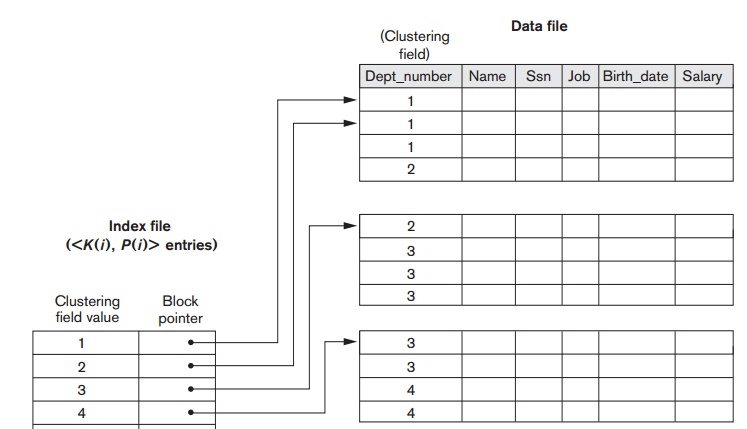

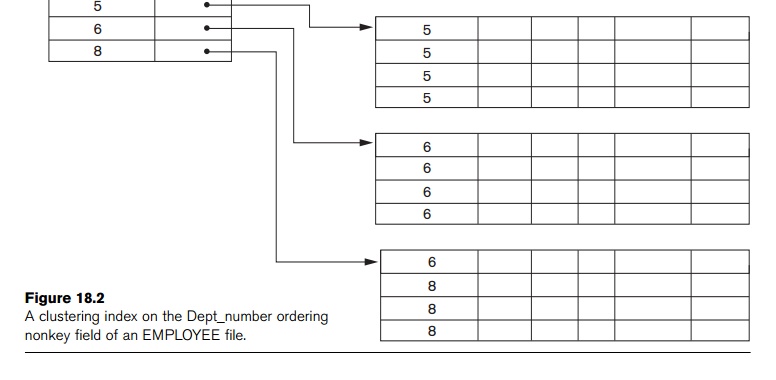

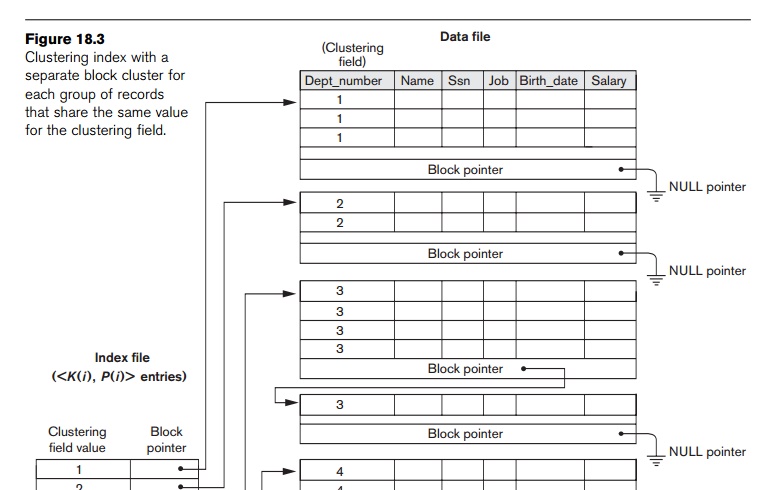

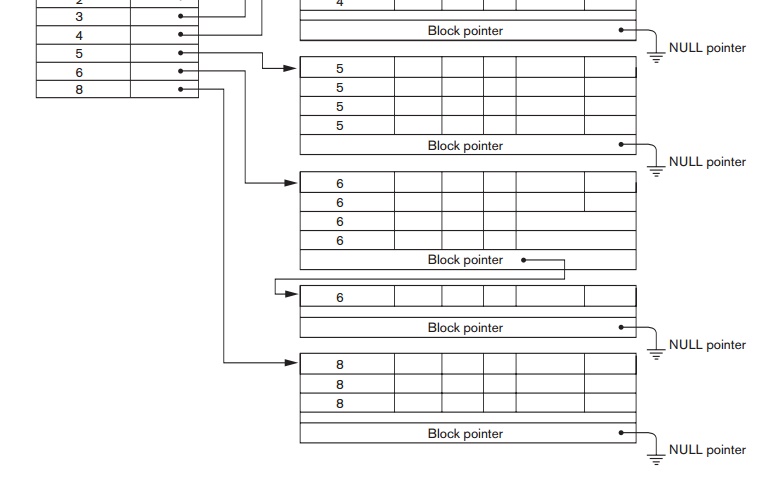

2. Clustering Indexes

If file records are physically ordered on a nonkey field—which does not have a distinct value for each

record—that field is called the clustering

field and the data file is called a clustered

file. We can create a different type of index, called a clustering index, to speed up retrieval of all the records that have the same

value for the clustering field. This differs from a primary index, which

requires that the ordering field of the data file have a distinct value for each record.

A clustering index is also an ordered file with two fields; the first

field is of the same type as the clustering field of the data file, and the

second field is a disk block pointer. There is one entry in the clustering

index for each distinct value of the

clustering field, and it contains the value and a pointer to the first block in the data file that has a

record with that value for its clustering field. Figure 18.2 shows an example.

Notice that record insertion and deletion still cause problems because the data

records are physically ordered. To alleviate the problem of insertion, it is

common to reserve a whole block (or a cluster of contiguous blocks) for each value of the clustering field; all

records with that value are placed in the block (or block cluster). This makes

insertion and deletion relatively straightforward. Figure 18.3 shows this

scheme.

A clustering index is another example of a nondense index because it has an entry for every distinct value of the indexing field,

which is a nonkey by definition and hence has duplicate values rather than a

unique value for every record in the file. There is some similarity between

Figures 18.1, 18.2, and 18.3 and Figures 17.11 and 17.12. An index is somewhat

similar to dynamic hashing (described in Section 17.8.3) and to the directory

structures used for extendible hashing. Both are searched to find a pointer to

the data block containing the desired record. A main difference is that an

index search uses the values of the search field itself, whereas a hash

directory search uses the binary hash value that is calculated by applying the

hash function to the search field.

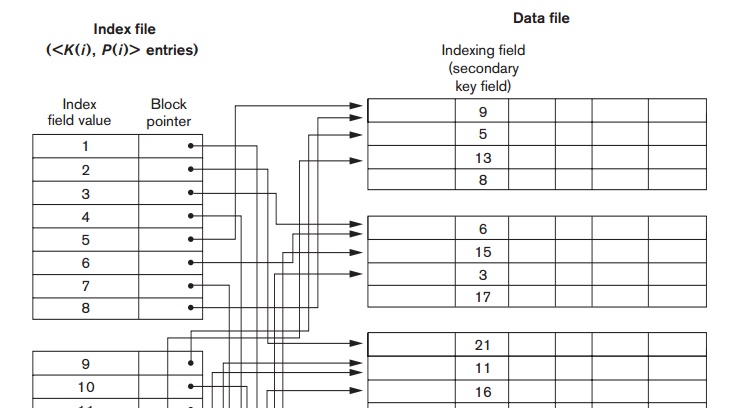

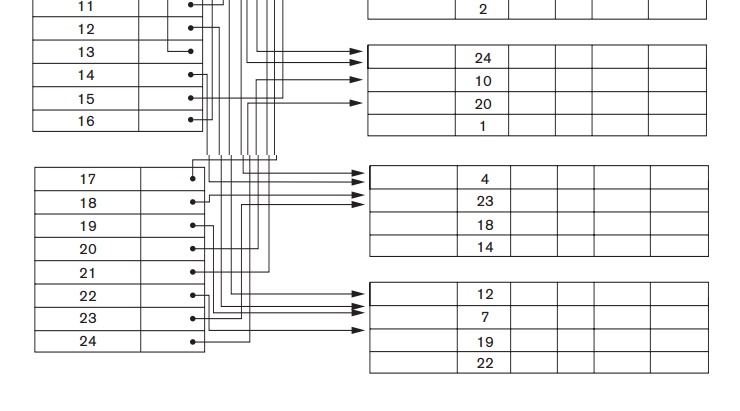

3. Secondary Indexes

A secondary index provides a secondary

means of accessing a data file for which some primary access already exists.

The data file records could be ordered, unordered, or hashed. The secondary

index may be created on a field that is a candidate key and has a unique value

in every record, or on a nonkey field with duplicate values. The index is

again an ordered file with two fields. The first field is of the same data type

as some nonordering field of the data

file that is an indexing field. The

second field is either a block

pointer or a record pointer. Many secondary indexes (and hence,

indexing fields) can be created for the same file—each represents an

additional means of accessing that file based on some specific field.

First we

consider a secondary index access structure on a key (unique) field that has a distinct value for every record. Such a

field is sometimes called a secondary

key; in the relational model, this would correspond to any UNIQUE key attribute or to the primary

key attribute of a table. In this case there is one index entry for each record in the data file, which

contains the value of the field for the record and a pointer either to the

block in which the record is stored or to the record itself. Hence, such an

index is dense.

Again we

refer to the two field values of index entry i as <K(i), P(i)>. The entries are ordered by value of K(i), so we can perform a binary search. Because the records of the data file are not physically ordered by values of the secondary key field, we cannot use block anchors. That is why an

index entry is created for each record in the data

file,

rather than for each block, as in the case of a primary index. Figure 18.4

illustrates a secondary index in which the pointers P(i) in the index entries

are block pointers, not record

pointers. Once the appropriate disk block is transferred to a main memory

buffer, a search for the desired record within the block can be carried out.

A

secondary index usually needs more storage space and longer search time than

does a primary index, because of its larger number of entries. However, the improvement in search time for an

arbitrary record is much greater for a secondary index than for a primary index, since we would have to do a linear search on the data file if the

secondary index did not exist. For a primary index, we could still use a binary

search on the main file, even if the index did not exist. Example 2 illustrates

the improvement in number of blocks accessed.

Example 2. Consider the file of Example 1

with r = 30,000 fixed-length records of size R = 100 bytes stored on a disk with block size B = 1024 bytes. The file has b

= 3000 blocks, as calculated in Example 1. Suppose we want to search for a

record with a specific value for the secondary key—a nonordering key field of

the file that is V = 9 bytes long.

Without the secondary index, to do a linear search on the file would require b/2 = 3000/2 = 1500 block accesses on

the average. Suppose that we con-struct a secondary index on that nonordering key field of the file. As in

Example 1, a block pointer is P = 6

bytes long, so each index entry is Ri

= (9 + 6) = 15 bytes, and the blocking factor for the index is bfri = (B/Ri) =

(1024/15) = 68 entries per block. In a dense secondary index such as this, the

total number of index entries ri

is equal to the number of records in

the data file, which is 30,000. The number of blocks needed for the index is

hence bi = (ri /bfri) = (3000/68) = 442 blocks.

A binary

search on this secondary index needs (log2bi) = (log2442) = 9 block accesses. To search

for a record using the index, we need an additional block access to the data

file for a total of 9 + 1 = 10 block accesses—a vast improvement over the 1500

block accesses needed on the average for a linear search, but slightly worse

than the 7 block accesses required for the primary index. This difference arose

because the primary index was nondense and hence shorter, with only 45 blocks

in length.

We can

also create a secondary index on a nonkey,

nonordering field of a file. In this case, numerous records in the data

file can have the same value for the indexing field. There are several options

for implementing such an index:

Option 1 is to include duplicate index entries with

the same K(i) value—one for each record. This would be a dense index.

Option 2 is to have variable-length records for the

index entries, with a repeating field for the pointer. We keep a list of

pointers <P(i, 1), ..., P(i, k)>

in the index entry for K(i)—one pointer to each block that contains

a record whose indexing field value equals K(i). In either option 1 or option 2, the

binary search algorithm on the index must be modified appropriately to account

for a variable number of index entries per index key value.

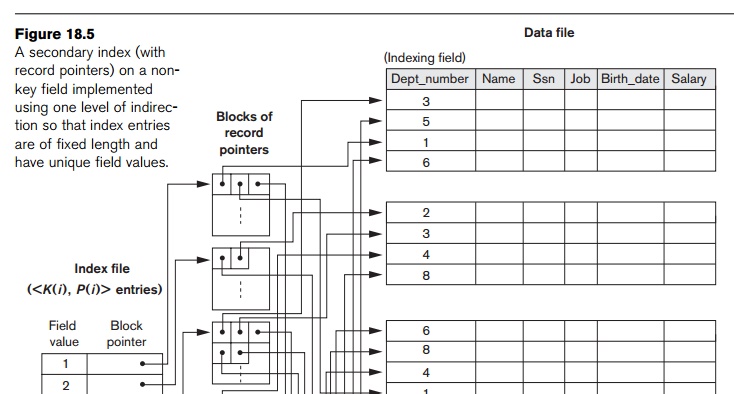

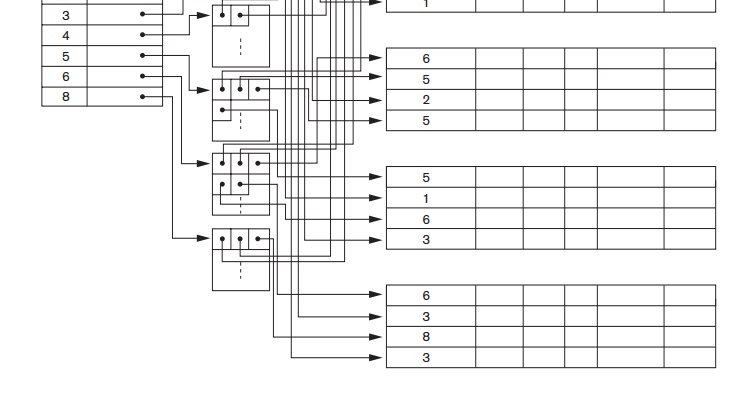

Option 3,

which is more commonly used, is to keep the index entries them-selves at a

fixed length and have a single entry for each index field value, but to create an extra level of indirection to handle the multiple pointers. In

this nondense scheme, the pointer P(i) in index entry <K(i),

P(i)>

points to a disk block, which contains a set

of record pointers; each record pointer in that disk block points to one of

the data file records with value K(i) for the index-ing field. If some

value K(i) occurs in too many records, so that their record pointers cannot

fit in a single disk block, a cluster or linked list of blocks is used. This

technique is illustrated in Figure 18.5. Retrieval via the index requires one

or more additional block accesses because of the extra level, but the algorithms

for searching the index and (more importantly) for inserting of new records in

the data file are straightforward. In addition, retrievals on complex selection

conditions may be handled by referring to the record pointers, without having

to retrieve many unnecessary records from the data file (see Exercise 18.23).

Notice

that a secondary index provides a logical

ordering on the records by the indexing field. If we access the records in

order of the entries in the secondary index, we get them in order of the

indexing field. The primary and clustering indexes assume that the field used

for physical ordering of records in

the file is the same as the indexing field.

4. Summary

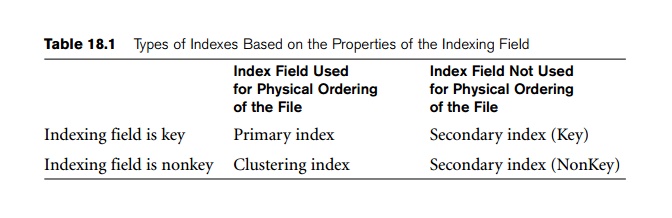

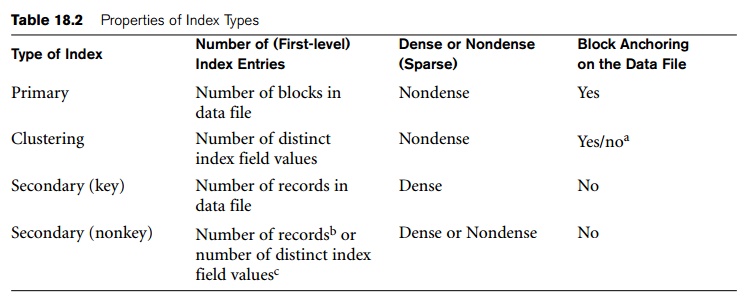

To conclude this section, we summarize the discussion of index types in

two tables. Table 18.1 shows the index field characteristics of each type of

ordered single-level index discussed—primary, clustering, and secondary. Table

18.2 summarizes the properties of each type of index by comparing the number of

index entries and specifying which indexes are dense and which use block

anchors of the data file.

Related Topics