Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Gastrointestinal Intubation and Special Nutritional Modalities

Tube Feedings With Nasogastric and Nasoenteric Devices

Tube Feedings With Nasogastric and

Nasoenteric Devices

Tube feedings are given to meet nutritional

requirements when oral intake is inadequate or not possible and the GI tract is

func-tioning normally. Tube feedings have several advantages over par-enteral

nutrition: they are low in cost, safe, well tolerated by the patient, and easy

to use both in extended care facilities and in the patient’s home. Tube

feedings have other advantages:

•

They preserve GI integrity by delivery of nutrients

and medications (antacids, simethicone, and metoclopramide) intraluminally

•

They preserve the normal sequence of intestinal and

hepatic metabolism

•

They maintain fat metabolism and lipoprotein

synthesis

•

They maintain normal insulin/glucagon ratios

Tube

feedings are delivered to the stomach (in the case of NG intubation or

gastrostomy) or to the distal duodenum or proximal jejunum (in the case of

nasoduodenal or nasojejunaltube feeding).

Nasoduodenal or nasojejunal feeding is indicatedwhen the esophagus and stomach

need to be bypassed or when the patient is at risk for aspiration (breathing fluids or foods into the trachea and lungs).

For long-term feedings (longer than 4 weeks), nasoduodenal, gastrostomy, or

jejunostomy tubes are preferred for administration of medications or food. The

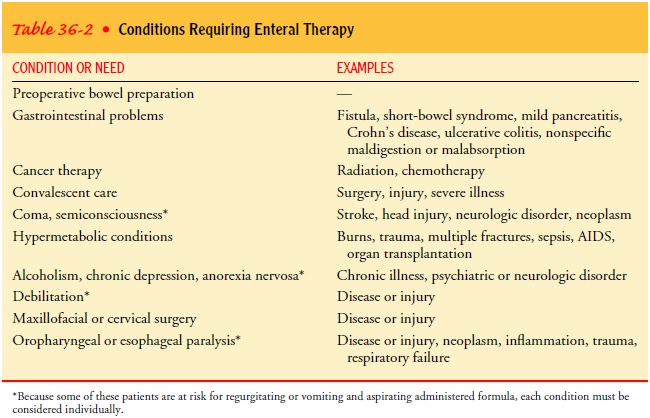

nu-merous conditions requiring enteral nutrition are summarized in Table 36-2.

OSMOSIS AND OSMOLALITY

Osmolality

is an important consideration for patients receiving tube feedings through the

duodenum or jejunum, because feed-ing formulas with a high osmolality may lead

to undesirable ef-fects, such as dumping syndrome (described below).

Fluid

balance is maintained by osmosis,

the process by which water moves through membranes from a dilute solution of

lower osmolality (ionic

concentration) to a more concentrated solutionof higher osmolality until both

solutions are of nearly equal os-molality. The osmolality of normal body fluids

is approximately 300 mOsm/kg. The body attempts to keep the osmolality of the

contents of the stomach and intestines at approximately this level.

Highly

concentrated solutions and certain foods can upset the normal fluid balance in

the body. Individual amino acids and carbohydrates are small particles that

have great osmotic effect. Proteins are extremely large particles and therefore

have less os-motic effect. Fats are not water-soluble and do not enter into a

solution in water; thus, they have no osmotic effect. Electrolytes, such as

sodium and potassium, are comparatively small particles; they have a great

effect on osmolality and consequently on the pa-tient’s ability to tolerate a

given solution.

When a

concentrated solution of high osmolality is taken in large amounts, water will

move to the stomach and intestines from fluid surrounding the organs and the

vascular compartment. The patient has a feeling of fullness, nausea, and

diarrhea; this causes dehydration, hypotension, and tachycardia, collectively

termed the dumping syndrome.

Starting with a more dilute solution and increasing the concentration over

several days can generally alleviate this problem. Patients vary in the degree

to which they tolerate the effects of high osmolality; usually debilitated

patients are more sensitive. The nurse needs to be knowledgeable about the

osmolality of the patient’s formula and needs to observe for and take steps to

prevent undesired effects.

TUBE FEEDING FORMULAS

The choice of formula to be delivered by tube feeding is influ-enced by the status of the GI tract and the nutritional needs of the patient. The formula characteristics evaluated include chem-ical composition of the nutrient source (protein, carbohydrates, fat), caloric density, osmolality, residue, bacteriologic safety, vita-mins, minerals, and cost.

Various

major formula types for tube feedings are available commercially. Blenderized

formulas can be made by the patient’s family or obtained in a ready-to-use form

that is carefully prepared according to directions. Commercially prepared

polymeric for-mulas (formulas with high molecular weight) are composed of

protein, carbohydrates, and fats in a high-molecular-weight form (Boost Plus,

TwoCal HN, Isosource). Chemically defined for-mulas contain predigested and

easy-to-absorb nutrients (Osmo-lite HN). Modular products contain only one

major nutrient, such as protein (Promote). Disease-specific formulas are available

for various conditions, such as renal failure (Nepro), severe chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease (Pulmocare). Nepro is high in calories and low in

electrolytes. It is ideal for patients who re-quire electrolyte and fluid

restriction. Pulmocare is high in fat and low in carbohydrates. Its high

density (1.5 calories/mL) is ideal for patients who require fluid restriction,

and it is also de-signed to reduce carbon dioxide production. Fiber has also

been added to formulas (Jevity) in an attempt to decrease the occur-rence of

diarrhea. Some feedings are given as supplements, and others are designed to

meet the patient’s total nutritional needs. Dietitians collaborate with

physicians and nurses in determining the best formula for the individual patient.

TUBE FEEDING ADMINISTRATION METHODS

Many

patients do not tolerate NG and nasoenteric tube feedings well. Often a medium-

or fine-bore Silastic nasoenteric tube is tolerated better than a plastic or

rubber tube. The finer-bore tube requires a finely dispersed formula to ensure

that the patency of the tube is maintained. For long-term tube feeding therapy,

a gas-trostomy or jejunostomy tube is used (see later discussion).

The

tube feeding method chosen depends on the location of the tube, patient

tolerance, convenience, and cost. Intermittent bolus feedings are administered

into the stomach (usually by gas-trostomy tube) in large amounts at designated

intervals and may be given 4 to 8 times per day. The intermittent gravity drip

is another method for administering tube feedings into the stomach and is

commonly used when the patient is at home. In this in-stance, the tube feeding

is administered over 30 minutes at desig-nated intervals. Both of these

tube-feeding methods are practical and inexpensive. However, the feedings

delivered at variable rates may be poorly tolerated and time-consuming.

The

continuous infusion method is used when feedings are administered into the

small intestine. This method is preferred for patients who are at risk for

aspiration or who tolerate the tube feedings poorly. The feedings are given

continuously at a con-stant rate by means of a pump. The continuous tube

feeding method, which requires a pump device, decreases abdominal distention,

gastric residuals, and the risk of aspiration. However, pumps are expensive,

and they permit the patient less flexibility than intermittent feedings do.

An

alternative to the continuous infusion method is cyclicfeeding. The infusion is given at a faster rate over a

shorter time(usually 8 to 12 hours). Feeding may be infused at night to avoid

interrupting the patient’s lifestyle. Cyclic continuous infusions may be

appropriate for patients who are being weaned from tube feedings to an oral

diet, as a supplement for a patient who cannot eat enough, and for patients at

home who need daytime hours free from the pump.

Tube

feeding solutions vary in terms of required preparation, consistency, and the

number of calories and supplemental vita-mins they contain. The choice of

solution depends on the size and location of the tube, the patient’s nutrient

needs, the type of nu-tritional supplement, the method of delivery, and the

convenience for the patient at home. A wide variety of containers, feeding

tubes and catheters, delivery systems, and pumps are available for use with

tube feedings.

Related Topics