Chapter: Forensic Medicine: Basic anatomy and physiology

The nervous system

The nervous system

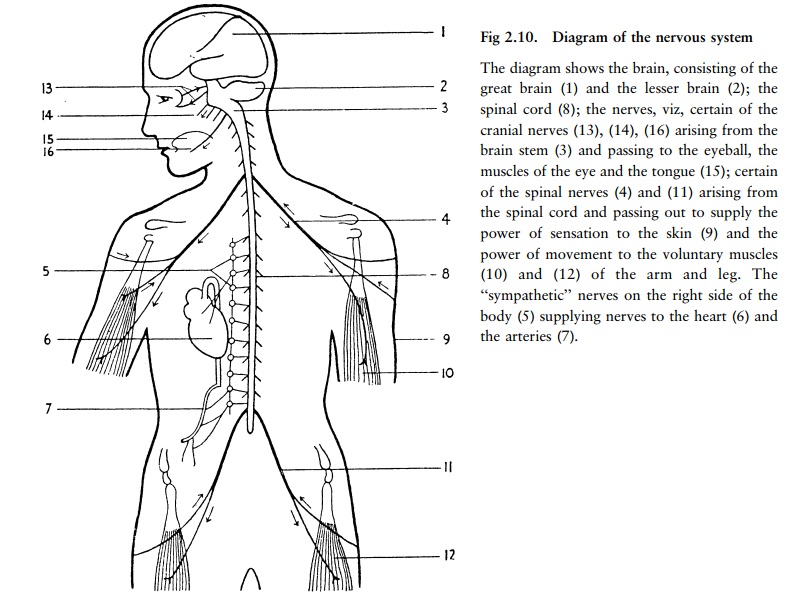

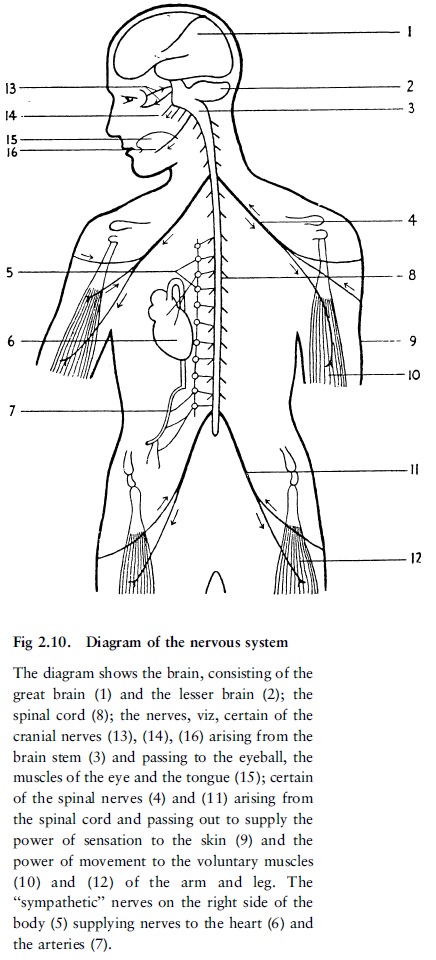

The nervous system (fig 2.10)

The nervous system controls and regulates all

the activities of the body, and is composed of the following:

a.

the brain

b.

the spinal cord

c.

the nerves

The brain

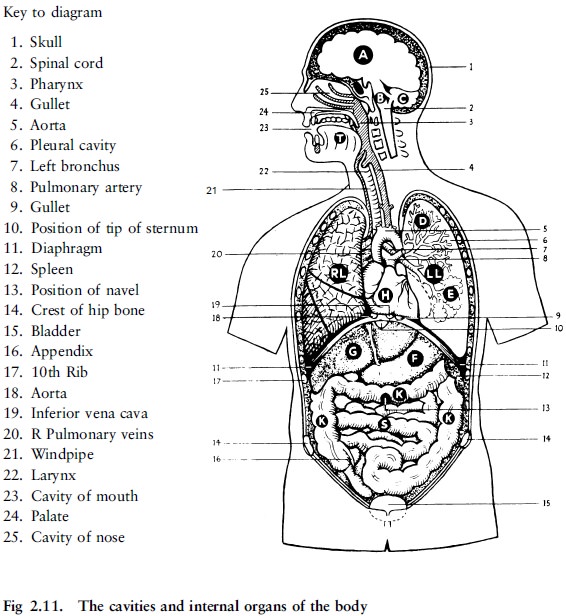

The brain (fig 2.10 and 2.11) lies in the cavity

of the skull. It is enclosed by several membranes with a small quantity of

fluid between each membrane, so that the brain rests upon a kind of water bed.

The brain is divided into three parts.

The great brain or cerebrum (fig 2.11A)

The great brain or cerebrum is composed of two

large hemispherical masses of nerve matter (the cerebral hemispheres) which are

connected with each other across the middle line and on the underside with the

brain stem.

Together these two hemispheres fill the greatest

part of the skull cavity. They are the seat of our conscious life, and of

thought and feeling. All voluntary impulses that activate the voluntary muscles

issue from them, and all impulses that convey sensation and so give us

knowledge of our surroundings go back to them. Serious disruption of the

working of the great brain results in unconsciousness.

The lesser brain or cerebellum (fig 2.11C)

The lesser brain or cerebellum lies in the lower

part of the back of the skull. It is attached in front to the brain stem.

The lesser brain is involved in the (usually

unconscious) maintenance of the balance of the body when normal body movements

are executed, for example standing, running, walking, jumping, et cetera.

The brain stem (fig 2.11B)

The brain stem forms the stalk of the brain,

lies within the skull and is connected at the top to the cerebrum or great

brain, at the back to the cerebellum or lesser brain, and on the underside it

runs continuous with the spinal cord through the opening in the base of the

skull as previously described.

The nerve centres responsible for the

involuntary regulation of breathing, heart-beat and circulation, lie in the

brain stem, which serves also to conduct impulses to and from the great brain,

the lesser brain and the spinal cord. An intact brain stem is necessary for

consciousness.

The spinal cord

The spinal cord (fig 2.11(2))

The spinal cord is a long, rounded cord of nerve

matter which begins at the opening in the base of the skull, where it is

continuous with the brain stem, and runs down through a canal which is enclosed

by the arches of the vertebrae, to end at the level of the upper part of the

loins. Its main function is to conduct impulses to the muscles downwards from

the brain via nerves (of which it is made up), and also to conduct upwards

impulses coming from the skin and other parts of the body via the nerves, thus

conveying sensations to the various parts of the brain.

The spinal cord is no thicker than a finger, and

the paths for the impulses to and from both sides of the body are all contained

within it, so that an injury to the cord need not be extensive in order to

damage or destroy these paths. Consequently, tearing or compression of the

spinal cord, which is liable to be caused by a fracture of the vertebrae, is

followed by more or less complete loss of power of movement (or paralysis) and

of feeling on both sides of the body below the seat of injury.

The nerves

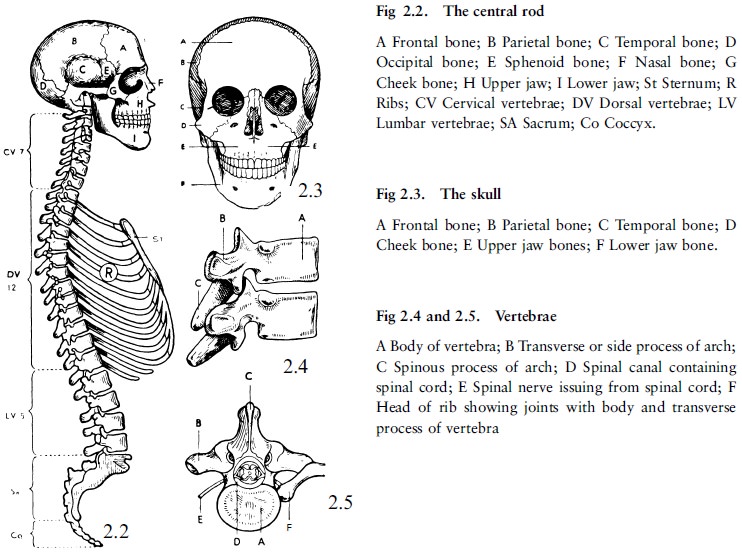

Between each pair of vertebrae a pair of nerves

(fig 2.5E; fig 2.10) issuesfrom the spinal cord, one on either side. Thirty-one

pairs of spinal nerves arise in this way from the spinal cord. They are strong

white cords of nerve matter.

The nerves divide and subdivide. Some go to a

skin area to which they supply power of sensation, others to a certain group of

muscles to which they supply power of movement. The spinal nerves supply

impulses in this way to the whole of the trunk and limbs, the neck and the back

of the scalp.

The organs of the special senses, the eyes

(sight), the ears, (hearing), the nose (smell), the tongue (taste), and also

the skin and the muscles of the face are in a similar way supplied by 12 pairs

of cranial nerves (fig 2.10) which issue from the brain stem and pass outward

through openings in the base of the skull.

Injury to a nerve (such as tearing or cutting)

is followed by loss of power of movement or paralysis of the particular

muscles, and loss of feeling in the particular area of skin supplied by that

nerve.

The following points must be noted:

·

The nerve matter of the great brain controls all voluntary movement and

sensation.

·

All impulses conveying sensation from the skin or from the organs of

special sense pass by way of the nerves to the spinal cord, or brain stem,

respectively, and thence to the great brain.

·

All impulses which produce voluntary movement of the muscles arise in

the great brain and pass through the brain stem and spinal cord and thence by

way of nerves to the muscles.

·

The paths conducting these impulses from skin to brain and from brain to

muscle, cross over the middle line on their way through the brain stem, so that

the muscles of the left side of the body are set in action by impulses from the

right side of the brain, and vice versa. In the same way, sensation arising in

the left side of the body is received in the right half of the brain, and vice

versa. That is why an injury to one half of the brain may be accompanied by

paralysis or loss of muscle power on the opposite side of the body.

The autonomous or sympathetic system and parasympathetic nerve system

The autonomous or sympathetic system and

parasympathetic nerve system (fig 2.10(5))

The internal organs of the body (heart, lungs,

liver, stomach, bowel, etc) are also supplied by nerves which issue along with

certain of the cranial nerves and with most of the spinal nerves from the brain

stem or the spinal cord respectively. These nerves, however, function virtually

independently of the control of the will. We cannot control the movements of

our internal organs by simply willing them to do something, and regulation of

the circulation of the blood, of digestion and other processes, goes on whether

we are asleep or awake, independently of the will, and controlled by the action

of these special nerves. It is by means of these nerves also that emotional

impulses, arising in the brain or spinal cord, affect the action of the heart,

blood vessels and other internal organs.

Most of these nerves issue from the spinal cord,

and, on leaving it, aregrouped together in a special arrangement, called the

sympathetic system. Although its action is independent of the will the

sympathetic system is not independent of the nervous system. It is simply a

portion of the nervous system responsible for regulating the activities of

certain of the internal organs.

Figure 2.10(5) shows a portion of the

sympathetic system diagrammatically: the connections with the spinal cord, and

nerves that supply the heart and blood vessels.

Related Topics