Chapter: Psychology: The Genetic and Evolutionary Roots of Behavior

The Biological Roots of Smiling

The Biological

Roots of Smiling

All animals interact with other

members of their species, whether as mates, parents, off-spring, or

competitors. And these interactions, in turn, usually depend on some kind of

communication as each animal lets the other know about its status and

intentions. Sometimes, the style of communications is species specific—pertaining to just one species—but often the

communication involves signals shared by many types of animals. Thus, many

mammals use the same “surrender” display to end a fight: They lie on their

backs, exposing their bellies and their throats, as a way of communicating

(roughly) “I know I’ve lost the fight; I’m giving in, and making myself

completely vulnerable to you. Let’s not fight any more.”

Humans, too, have various ways of

communicating their status and intentions. In many circumstances, of course, we

use language—and so we can, with enormous preci-sion, convey our message to a

conversational partner. We also communicate a great deal by our body

position—how close we stand to another person, how we hold our arms, how we

orient our bodies, and so on. Our faces convey still more information—

including the various facial displays that express emotion.

THE ORIGINS OF SMILING

Virtually all babies start

smiling at a very young age. The first smiles are detectable in infants just 1

month old; smiles directed toward other people are evident a month or so later.

One might think that babies learn to

smile by observing others and imitating the facial expressions they see, but

evidence argues against this proposal. For example, babies who are born blind

start smiling at the same age as sighted babies, and—just like sighted

babies—they’re most likely to smile when interacting with others and when

they’re com-fortable and well fed. Likewise, one study compared the facial

expressions of three groups of athletes receiving their award medals at the

2004 Paralympic Games (Matsumoto & Willingham, 2009). One group had been

blind since birth; a second group had some years of visual experience but was

now fully blind; a third group had normal sight. The study showed essentially

no difference among these groups in their facial expressions.

Apparently, then, the behavior of

smiling is something that humans do

without a history of observational learning. On this basis, we might expect to

find smiles in all humans in all cultures—and we do. In other words, the

behavior of smiling is species general—observable

in virtually all members of our species. In one study, American actors were

photographed while conveying emotions such as happiness, sadness, anger, and

fear. These photos were then shown to members of an isolated tribe in New

Guinea, and individuals there were asked to pick the emotion label that matched

each photograph. Then the procedure was reversed: The New Guinea tribesmen were

asked to portray the facial expression appropriate to specific situations, such

as happiness at the return of a friend or anger at the start of a fight.

Photographs of their performances were shown to American college students, who

were asked to judge which situation the tribesmen had been trying to convey in

each photo (Ekman & Friesen, 1975).

Performance in these tasks was quite good—the New Guinea tribesmen were generally able to recognize the Americans’ expressions, and vice versa. Importantly, performance varied from one emotion to the next, with (for example) disgust and fear more difficult to recognize than sadness. The expression producing the most accurate identification, though, was happiness. Smiles are apparently a universal human signal (Ekman, 1994; Izard, 1994).

SMILES IN OTHER SPECIES

The behavior of smiling is not

just shared across cultures; it is also shared across species. In other words, we find similar emotional expressions in

animals with genomes simi-lar to ours. Thus, smiling is species general (found in the entire species), but it is not species specific (found only in one

species).

Darwin himself was especially

interested in this point and drew evidence from several sources, including his

own observations of animals at the London Zoo. He eventually published his

findings in a book entitled The

Expression of the Emotions inMan and Animals (Darwin, 1872). Darwin’s

observations made it clear to him that therewere different types of smiles—a

point that has been well confirmed in more recent research. The smiles can be

differentiated in terms of the situations that elicit them; they can also be

differentiated by their exact appearance. And, remarkably, the various types of

smiles can be identified as readily in other species as they can in humans.

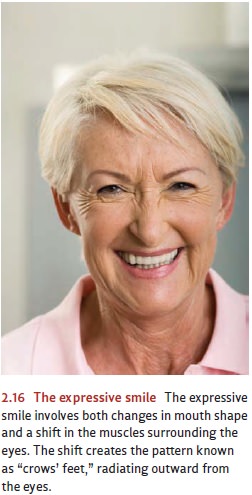

One type of smile seems

straightforwardly expressive of your

inner state, and it’s pro-duced when you feel happy. This smile will be

produced even if no other people are around, and it involves both a change in

mouth shape (the corners of the lips are pulled upward) and a shift in the

muscles of the upper face, surrounding the eyes. The latter shift creates the

pattern often called crow’s feet—lines

that radiate outward from the eyes (Figure 2.16).

The expressive smile obviously

occurs in humans when events or stimuli please us, or when we hear a good joke.

A similar expression occurs in young monkeys in the midst of play; many

observers interpret it as a signal between monkeys that their pushing and

tumbling is playful rather than aggressive. Smiles in humans also promote

cooperation: A smile on someone’s face often signals their intention to

cooperate and, at the same time, the sight of a smile tends to evoke positive

feelings in the perceiver, making cooperation more likely.

A different sort of smile seems

more polite in nature, and it’s rarely

produced without an audience. In this smile, one pulls the corners of one’s

lips upward but with little movement of the eyes. This sort of smile seems to

function as a greeting and also as a means of defusing situations that

otherwise might be tense or embarrassing (Goldenthal, Johnston, & Kraut,

1981). It’s also a smile people use when they wish to simulate happiness (e.g.,

when pretending to have fun at a dreadful party, or when trying to persuade

someone they’re amusing when they are actually boring).

This polite smile can also be

found in nonhuman primates, where it generally takes a form of drawing back the

lips and revealing the teeth, but keeping the teeth plainly closed. In monkeys,

this smile may be a gesture of submission at the end of a conflict, or it may

be intended to avoid a conflict. It’s

as if one monkey is saying to another, “Look—my teeth are closed; I’m obviously

not preparing to bite you or fight you. So be good to me” (Figure 2.17).

What does all of this imply about

the origins of smiling? The fact that

smiles emerge with no history of learning (e.g., in individuals blind since

birth) tells us that this behavior is strongly shaped by inborn (genetic)

factors. This claim is certainly consis-tent with the universality of smiling

(across cultures and across species), which sug-gests an ancient origin for

this behavior: It’s likely that the smiles evident in American college

students, in New Guinea tribesmen, or in playful monkeys were shaped by natural

selection long ago, in the ancestors shared by all of these modern primates.

Moreover, the obvious function of smiles in modern creatures supplies an

important

clue as to why the behavior of smiling served our ancestors well—by providing

a signal about emotions and intentions that facilitated social interactions.

These observations in turn provide a clear indication of why this behavior was

promoted and preserved by natural selection. All of these are key points

whenever we try to establish—whether we’re focusing on smiles or any other

trait—how and why the trait evolved.

Related Topics