Chapter: Compilers : Principles, Techniques, & Tools : Run-Time Environments

Short-Pause Garbage Collection

Short-Pause Garbage Collection

1 Incremental Garbage Collection

2 Incremental Reachability

Analysis

3 Partial-Collection Basics

4 Generational Garbage Collection

5 The Train Algorithm

6 Exercises for Section 7.7

Simple trace-based collectors do stop-the-world-style garbage

collection, which may introduce long pauses into the execution of user

programs. We can reduce the length of the pauses by performing garbage

collection one part at a time. We can divide the work in time, by interleaving

garbage collection with the mutation, or we can divide the work in space by

collecting a subset of the garbage at a time. The former

is known as incremental collection

and the latter is

known as partial collection.

An incremental collector breaks up the reachability analysis into

smaller units, allowing the mutator to run between these execution units. The

reachable set changes as the mutator executes, so incremental collection is

complex. As we shall see in Section 7.7.1, finding a slightly conservative

answer can make tracing more efficient.

The best known of partial-collection algorithms is generational garbage col-lection] it partitions objects according

to how long they have been allocated and

collects the newly created objects more often because they tend to have a

shorter lifetime. An alternative algorithm, the train algorithm, also collects a subset of garbage at a time, and

is best applied to more mature objects. These two algorithms can be used

together to create a partial collector that handles younger and older objects

differently. We discuss the basic algorithm behind partial collection in

Section 7.7.3, and then describe in more detail how the generational and train

algorithms work.

Ideas from both incremental and partial collection can be adapted to

cre-ate an algorithm that collects objects in parallel on a multiprocessor; see

Sec-tion 7.8.1.

1. Incremental Garbage Collection

Incremental collectors are conservative. While a garbage collector must

not collect objects that are not garbage, it does not have to collect all the

garbage in each round. We refer to the garbage left behind after collection as floating garbage. Of course it is desirable to minimize floating garbage. In

particular, an incremental collector

should not leave behind any garbage that was not reachable at the beginning of

a collection cycle. If we can be sure of such a collection guarantee, then any

garbage not collected in one round will be collected in the next, and no memory

is leaked because of this approach to garbage collection.

In other words, incremental collectors play it safe by overestimating

the set of reachable objects. They first process the program's root set

atomically, with-out interference from the mutator. After finding the initial

set of unscanned objects, the mutator's actions are interleaved with the

tracing step. During this period, any of the mutator's actions that may change

reachability are recorded succinctly, in a side table, so that the collector

can make the necessary ad-justments when it resumes execution. If space is

exhausted before tracing com-pletes, the collector completes the tracing

process, without allowing the mutator to execute. In any event, when tracing is

done, space is reclaimed atomically.

Precision of Incremental Collection

Once an object becomes unreachable, it is not possible for the object to

become reachable again. Thus, as garbage collection and mutation proceed, the

set of reachable objects can only

Grow due to new objects allocated

after garbage collection starts, and

Shrink by losing references to

allocated objects.

Let the set of reachable objects at the beginning of garbage collection

be R; let New be the set of allocated objects during garbage collection, and

let Lost be the set of objects that

have become unreachable due to lost references since tracing began. The set of

objects reachable when tracing completes is

It is expensive to reestablish an object's reachability every time a

mutator loses a reference to the object, so incremental collectors do not

attempt to collect all the garbage at the end of tracing. Any garbage left

behind — floating garbage — should be a subset of the Lost objects. Expressed formally, the set S of objects found by tracing must satisfy

Simple Incremental

Tracing

We first describe a straightforward tracing algorithm that finds the

upper bound R U New. The behavior of

the mutator is modified during the tracing as follows:

All references that existed

before garbage collection are preserved; that is, before the mutator overwrites

a reference, its old value is remembered and treated like an additional

unscanned object containing just that reference.

All objects created are

considered reachable immediately and are placed in the Unscanned state.

This scheme is conservative but correct, because it finds R, the set of all the objects reachable

before garbage collection, plus New,

the set of all the newly allocated objects. However, the cost is high, because

the algorithm intercepts all write operations and remembers all the overwritten

references. Some of this work is unnecessary because it may involve objects

that are unreachable at the end of garbage collection. We could avoid some of

this work and also improve the algorithm's precision if we could detect when

the overwritten references point to objects that are unreachable when this

round of garbage collection ends. The next algorithm goes fairly far in these

two directions.

2. Incremental

Reachability Analysis

If we interleave the mutator with a basic tracing algorithm, such as

Algo-rithm 7.12, then some reachable objects may be misclassified as

unreachable. The problem is that the actions of the mutator can violate a key

invariant of the algorithm; namely, a Scanned

object can only contain references to other Scanned

or Unscanned objects, never to Unreached objects. Consider the

fol-lowing scenario:

1. The garbage collector finds object o1 reachable and scans the pointers within o1, thereby putting 01 in

the Scanned state.

2. The mutator stores a reference to an Unreached (but reachable) object o into the Scanned object

o1. It does so by copying a reference

to o from an object o2 that is

currently in the Unreached or Unscanned state.

3. The mutator loses the reference to o in object o 2 . It may have overwrit-ten o 2 's reference to o before the

reference is scanned, or o2 may have become unreachable and never have reached the Unscanned state to have its references

scanned.

Now, o is reachable through

object 01, but the garbage collector

may have seen neither the reference to o

in oi nor the reference to o in o2 •

The key to a more precise, yet correct, incremental trace is that we

must note all copies of references to currently unreached objects from an

object that has not been scanned to one that has. To intercept problematic

transfers of references, the algorithm can modify the mutator's action during

tracing in any of the following ways:

• Write Barriers. Intercept writes

of references into a

Scanned object ox, when the

reference is to an Unreached object o. In this case, classify o as reachable

and place it in the Unscanned set.

Alternatively, place the written object o1

back in the Unscanned set so we can rescan it.

• Read Barriers. Intercept

the reads of references

in Unreached or Unscanned objects.

Whenever the mutator reads a reference to an object o from an object in

either the Unreached or Unscanned state, classify o as reachable and place it in the

Unscanned set.

• Transfer Barriers. Intercept the loss of the original reference in an Un-reached or Unscanned object. Whenever the mutator overwrites a ref-erence in

an Unreached or Unscanned object, save the reference being overwritten, classify it

as reachable, and place the reference itself in the

Unscanned set.

None of the options above finds the smallest set of reachable objects.

If the tracing process determines an object to be reachable, it stays reachable

even though all references to it are overwritten before tracing completes. That

is, the set of reachable objects found is between (R U New) — Lost and (R U New).

Write barriers are the most efficient of the options outlined above.

Read barriers are more expensive because typically there are many more reads

than there are writes. Transfer barriers are not competitive; because many

objects "die young," this approach would retain many unreachable

objects.

Implementing Write Barriers

We can implement write barriers in two ways. The first approach is to

re-member, during a mutation phase, all new references written into the Scanned objects. We can place all these

references in a list; the size of the list is propor-tional to the number of

write operations to Scanned objects,

unless duplicates are removed from the list. Note that references on the list

may later be over-written themselves and potentially could be ignored.

The second, more efficient approach is to remember the locations where

the writes occur. We may remember them as a list of locations written, possibly

with duplicates eliminated. Note it is not important that we pinpoint the exact

locations written, as long as all the locations that have been written are

rescanned. Thus, there are several techniques that allow us to remember less

detail about exactly where the rewritten locations are.

Instead of remembering the exact

address or the object and field that is written, we can remember just the

objects that hold the written fields.

We can divide the address space

into fixed-size blocks, known as cards,

and use a bit array to remember the cards that have been written into.

We can choose to remember the

pages that contain the written locations. We can simply protect the pages

containing Scanned objects. Then, any

writes into Scanned objects will be

detected without executing any ex-plicit instructions, because they will cause

a protection violation, and the operating system will raise a program

exception.

In general, by coarsening the granularity at which we remember the

written locations, less storage is needed, at the expense of increasing the

amount of rescanning performed. In the first scheme, all references in the

modified objects will have to be rescanned, regardless of which reference was

actually modified. In the last two schemes, all reachable objects in the

modified cards or modified pages need to be rescanned at the end of the tracing

process.

Combining Incremental and

Copying Techniques

The above methods are sufficient for mark-and-sweep garbage collection.

Copy-ing collection is slightly more complicated, because of its interaction

with the mutator. Objects in the Scanned

or Unscanned states have two

addresses, one in the From semispace

and one in the To semispace. As in

Algorithm 7.16, we must keep a mapping from the old address of an object to its

relocated address.

There are two choices for how we update the references. First, we can

have the mutator make all the changes in the From space, and only at the end of garbage collection do we update

all the pointers and copy all the contents over to the To space. Second, we can instead make changes to the representation

in the To space. Whenever the mutator

dereferences a pointer to the From

space, the pointer is translated to a new location in the To space if one exists. All the pointers need to be translated to

point to the To space in the end.

3. Partial-Collection Basics

The fundamental fact is that objects typically "die young." It

has been found that usually between 80% and 98% of all newly allocated objects

die within a few million instructions, or before another megabyte has been allocated.

That is, objects often become unreachable before any garbage collection is

invoked. Thus, is it quite cost effective to garbage collect new objects

frequently.

Yet, objects that survive a collection once are likely to survive many

more collections. With the garbage collectors described so far, the same mature

objects will be found to be reachable over and over again and, in the case of

copying collectors, copied over and over again, in every round of garbage

collection. Generational garbage collection works most frequently on the area

of the heap that contains the youngest objects, so it tends to collect a lot of

garbage for relatively little work. The train algorithm, on the other hand,

does not spend a large proportion of time on young objects, but it does limit

the pauses due to garbage collection. Thus,

a good combination of strategies is to use generational collection for

young objects, and once an object

becomes sufficiently mature, to "promote" it to a separate heap that

is managed by the train algorithm.

We refer to the set of objects to be collected on one round of partial

collection as the target set and the

rest of the objects as the stable

set. Ideally, a partial collector should reclaim all objects in the target set

that are unreachable from the program's root set. However, doing so would

require tracing all objects, which is what we try to avoid in the first place.

Instead, partial collectors conservatively reclaim only those objects that

cannot be reached through either the root set of the program or the stable set.

Since some objects in the stable set may themselves be unreachable, it is

possible that we shall treat as reachable some objects in the target set that

really have no path from the root set.

We can adapt the garbage collectors described in Sections 7.6.1 and

7.6.4 to work in a partial manner by changing the definition of the "root

set." Instead of referring to just the objects held in the registers,

stack and global variables, the root set now also includes all the objects in

the stable set that point to objects in the target set. References from target

objects to other target objects are traced as before to find all the reachable

objects. We can ignore all pointers to stable objects, because these objects

are all considered reachable in this round of partial collection.

To identify those stable objects that reference target objects, we can

adopt techniques similar to those used in incremental garbage collection. In

incremen-tal collection, we need to remember all the writes of references from

scanned objects to unreached objects during the tracing process. Here we need

to re-member all the writes of references from the stable objects to the target

objects throughout the mutator's execution. Whenever the mutator stores into a

sta-ble object a reference to an object in the target set, we remember either

the reference or the location of the write. We refer to the set of objects

holding references from the stable to the target objects as the remembered set for this set of target

objects. As discussed in Section 7.7.2, we can compress the repre-sentation of

a remembered set by recording only the card or page in which the written object

is found.

Partial garbage collectors are often implemented as copying garbage

collec-tors. Noncopying collectors can also be implemented by using linked

lists to keep track of the reachable objects. The "generational"

scheme described below is an example of how copying may be combined with

partial collection.

4. Generational Garbage

Collection

Generational garbage collection is an effective way to exploit the

property that most objects die young. The heap storage in generational garbage

collection is separated into a series of partitions. We shall use the

convention of numbering them 0 , 1 , 2 , . . . ,n, with the lower-numbered

partitions holding the younger objects. Objects are first created in partition

0. When this partition fills up, it is garbage collected, and its reachable

objects are moved into partition 1. Now, with partition 0 empty again, we

resume allocating new objects in that partition. When partition 0 again fills,6 it is

garbage collected and its reachable objects copied into partition 1, where they

join the previously copied objects.

This pattern repeats until partition 1 also fills up, at which point

garbage collection is applied to partitions 0 and 1.

In general, each round of garbage collection is applied to all

partitions num-bered i or below, for

some i; the proper i to choose is the highest-numbered

partition that is currently full. Each time an object survives a collection

(i.e., it is found to be reachable), it is promoted to the next higher

partition from the one it occupies, until it reaches the oldest partition, the

one numbered n. Using the terminology introduced in Section 7.7.3, when

partitions i and

below are garbage collected, the partitions from 0 through i make up the target set, and all

partitions above i comprise the

stable set. To support finding root sets for all possible partial collections,

we keep for each partition i a remembered set, consisting of all the objects in partitions above i that point to objects in set i. The root set for a partial

collection invoked on set i includes

the remembered sets for partition i and below.

In this scheme, all partitions

below i are collected whenever we

collect i.

There are two reasons for this policy:

Since younger generations contain

more garbage and are collected more often anyway, we may as well collect them

along with an older generation.

Following this strategy, we need

to remember only the references pointing from an older generation to a newer

generation. That is, neither writes to objects in the youngest generation nor

promoting objects to the next generation causes updates to any remembered set.

If we were to collect a partition without a younger one, the younger generation

would become part of the stable set, and we would have to remember references

that point from younger to older generations as well.

In summary, this scheme collects younger generations more often, and

collections of these generations are particularly cost effective, since

"objects die young." Garbage collection of older generations takes

more time, since it includes the collection of all the younger generations and

contains proportionally less garbage. Nonetheless, older generations do need to

be collected once in a while to remove unreachable objects. The oldest

generation holds the most mature objects; its collection is expensive because

it is equivalent to a full collection. That is, generational collectors

occasionally require that the full tracing step be performed and therefore can

introduce long pauses into a program's execution. An alternative for handling

mature objects only is discussed next.

5. The Train Algorithm

While the generational approach is very efficient for the handling of

immature objects, it is less efficient for the mature objects, since mature

objects are moved every time there is a collection involving them, and they are

quite unlikely to be garbage. A different approach to incremental collection,

called the train algorithm, was developed to improve the handling of mature objects.

It can be used for collecting all

garbage, but it is probably better to use the generational approach for

immature objects and, only after they have survived a few rounds of collection,

"promote" them to another heap, managed by the train algorithm.

Another advantage to the train algorithm is that we never have to do a complete

garbage collection, as we do occasionally for generational garbage collection.

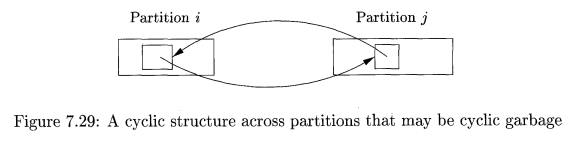

To motivate the train algorithm, let us look at a simple example of why

it is necessary, in the generational approach, to have occasional all-inclusive

rounds of garbage collection. Figure 7.29 shows two mutually linked objects in

two partitions i and j, where j > i. Since both objects have pointers from outside their

partition, a collection of only partition i

or only partition j could never

collect either of these objects. Yet they may in fact be part of a cyclic

garbage structure with no links from the outside. In general, the

"links" between the objects shown may involve many objects and long

chains of references.

In generational garbage collection, we eventually collect partition j, and since i < j, we also collect i

at that time. Then, the cyclic structure will be completely contained in the

portion of the heap being collected, and we can tell if it truly is garbage.

However, if we never have a round of collection that includes both i and j, we would have a problem with cyclic garbage, just as we did with

reference counting for garbage collection.

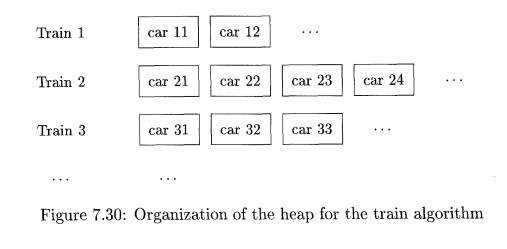

The train algorithm uses fixed-length partitions, called cars; a car might be a single disk

block, provided there are no objects larger than disk blocks, or the car size

could be larger, but it is fixed once and for all. Cars are organized into trains. There is no limit to the number

of cars in a train, and no limit to the number

of trains. There is a lexicographic order to cars: first order by train number,

and within a train, order by car number, as in Fig. 7.30.

There are two ways that garbage is collected by the train algorithm:

The first car in lexicographic order (that is, the first remaining car

of the first remaining train) is collected in one incremental garbage-collection

step. This step is similar to collection of the first partition in the

gener-ational algorithm, since we maintain a "remembered" list of all

pointers from outside the car. Here, we identify objects with no references at

all, as well as garbage cycles that are contained completely within this car.

Reachable objects in the car are always moved to some other car, so each

garbage-collected car becomes empty and can be removed from the train.

Sometimes, the first train has no

external references. That is, there are no pointers from the root set to any

car of the train, and the remembered sets for the cars contain only references

from other cars in the train, not from other trains. In this situation, the

train is a huge collection of cyclic garbage, and we delete the entire train.

Remembered Sets

We now give the details of the train algorithm. Each car has a

remembered set consisting of all references to objects in the car from

Objects in higher-numbered cars

of the same train, and

Objects in higher-numbered

trains.

In addition, each train has a remembered set consisting of all

references from higher-numbered trains. That is, the remembered set for a train

is the union of the remembered sets for its cars, except for those references

that are internal to the train. It is

thus possible to represent both kinds of remembered sets by dividing the

remembered sets for the cars into "internal" (same train) and

"external" (other trains) portions.

Note that references to objects can come from anywhere, not just from

lexicographically higher cars. However, the two garbage-collection processes

deal with the first car of the first train, and the entire first train,

respectively. Thus, when it is time to use the remembered sets in a garbage

collection, there is nothing earlier from which references could come, and

therefore there is no point in remembering references to higher cars at any

time. We must be careful, of course, to manage the remembered sets properly,

changing them whenever the mutator modifies references in any object.

Managing Trains

Our objective is to draw out of the first train all objects that are not

cyclic garbage. Then, the first train either becomes nothing but cyclic garbage

and is therefore collected at the next round of garbage collection, or if the

garbage is not cyclic, then its cars may be collected one at a time.

We therefore need to start new trains occasionally, even though there is

no limit on the number of cars in one train, and we could in principle simply

add new cars to a single train, every time we needed more space. For example,

we could start a new train after every k

object creations, for some k. That

is, in general, a new object is placed in the last car of the last train, if

there is room, or in a new car that is added to the end of the last train, if

there is no room. However, periodically, we instead start a new train with one

car, and place the new object there.

Garbage Collecting a Car

The heart of the train algorithm is how we process the first car of the

first train during a round of garbage collection. Initially, the reachable set

is taken to be the objects of that car with references from the root set and

those with references in the remembered set for that car. We then scan these

objects as in a mark-and-sweep collector, but we do not scan any reached

objects outside the one car being collected. After this tracing, some objects

in the car may be identified as garbage. There is no need to reclaim their

space, because the entire car is going to disappear anyway.

However, there are likely to be some reachable objects in the car, and

these must be moved somewhere else. The rules for moving an object are:

• If there is a reference in the remembered set from any other train

(which will be higher-numbered than the train of the car being collected), then

move the object to one of those trains. If there is room, the object can go in

some existing car of the train from which a reference emanates, or it can go in

a new, last car if there is no room.

• If there is no reference from other trains, but there are references

from the root set or from the first train, then move the object to any other

car of the same train, creating a new, last car if there is no room. If

possible, pick a car from which there is a reference, to help bring cyclic

structures to a single car.

Panic M o d e

There is one problem with the rules above. In order to be sure that all

garbage will eventually be collected, we need to be sure that every train

eventually becomes the first train, and if this train is not cyclic garbage,

then eventually all cars of that train are removed and the train disappears one

car at a time. However, by rule (2) above, collecting the first car of the

first train can produce a new last car. It cannot produce two or more new cars,

since surely all the objects of the first car can fit in the new, last car.

However, could we be in a situation where each collection step for a train

results in a new car being added, and we never get finished with this train and

move on to the other trains?

The answer is, unfortunately, that such a situation is possible. The

problem arises if we have a large, cyclic, nongarbage structure, and the

mutator manages to change references in such a way that we never see, at the

time we collect a car, any references from higher trains in the remembered set.

If even one object is removed from the train during the collection of a car,

then we are OK, since no new objects are added to the first train, and

therefore the first train will surely run out of objects eventually. However,

there may be no garbage at all that we can collect at a stage, and we run the

risk of a loop where we perpetually garbage collect only the current first

train.

To avoid this problem, we need to behave differently whenever we encounter

a futile garbage collection, that is,

a car from which not even one object can be deleted as garbage or moved to

another train. In this "panic mode," we make two changes:

When a reference to an object in

the first train is rewritten, we maintain the reference as a new member of the

root set.

When garbage collecting, if an

object in the first car has a reference from the root set, including dummy

references set up by point (1), then we move that object to another train, even

if it has no references from other trains. It is not important which train we

move it to, as long as it is not the first train.

In this way, if there are any references from outside the first train to

objects in the first train, these references are considered as we collect every

car, and eventually some object will be removed from that train. We can then

leave panic mode and proceed normally, sure that the current first train is now

smaller than it was.

6. Exercises for Section 7.7

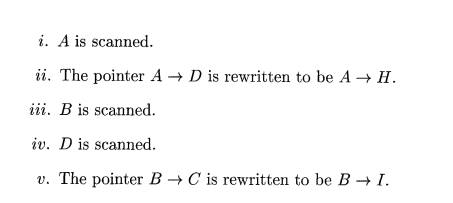

E x e r c i s e 7 . 7 . 1 : Suppose that the network of objects from

Fig. 7.20 is managed by an incremental algorithm that uses the four lists Unreached, Unscanned, Scanned, and Free, as in Baker's algorithm. To be specific, the Unscanned list is managed as a queue, and when more than one object is to be

placed on this list due to the scanning of one object, we do so in alphabetical

order. Suppose also that we use write barriers to assure that no reachable

object is made garbage.

Starting with A and

B on the Unscanned list, suppose the

following events occur:

Simulate the entire incremental garbage collection, assuming no more

pointers are rewritten. Which objects are garbage? Which objects are placed on

the Free list?

Exercise 7 . 7 . 2: Repeat

Exercise 7.7.1 on the assumption that

Events (ii) and (v)

are interchanged in order.

Events (ii)

and (v) occur before

(i), (Hi), and (iv).

Exercise 7 . 7 . 3 : Suppose the heap consists of exactly the nine cars on three trains shown in Fig. 7.30 (i.e.,

ignore the ellipses). Object o in car

11 has references from cars 12, 23, and 32. When we garbage collect car 11,

where might o wind up?

Exercise 7 . 7 . 4 : Repeat Exercise 7.7.3 for the

cases that o has

Only references from cars 22 and

31.

No references other than from car

11.

Exercise 7 . 7 . 5 : Suppose the heap consists of exactly the nine cars on three trains shown in Fig. 7.30 (i.e.,

ignore the ellipses). We are currently in panic mode. Object oi in car 11 has only one reference,

from object o2 in car 12. That reference is rewritten. When we garbage collect car 11,

what could happen to O1?

Related Topics