Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: End-of-Life Care

Settings for End-of-Life Care: Hospice Care

HOSPICE

CARE

Hospice in the United States is not a place, but a concept of care in

which the end of life is viewed as a developmental stage. The root of the word

hospice is hospes, meaning “host.”

Historically, hospice has referred to a shelter or way station for weary

travelers on a pilgrimage (Bennahum, 1996). In the years that followed

Kübler-Ross’s groundbreaking work, the concept of hospice care as an

alternative to depersonalized death in institutions began as a grassroots

movement. Her work, and the development of the con-cept of hospice in England

by Dr. Cicely Saunders, resulted in recognition of gaps in the existing system

of care for the terminally ill (Amenta, 1986). Hospice care began in response

to “noticeable gaps . . . (1) between treating the disease and treating the

person, (2) between

technological research and psycho-social support, and

(3) between

the general denial of the fact of death in our society and the acceptance of

death by those who face it”. According to Saunders, who founded the

world-renowned St. Christopher’s Hospice in London (Bennahum, 1996), the

principles underlying hospice are as follows:

·

Death

must be accepted.

·

The patient’s

total care is best managed by an interdisciplinary team whose members

communicate regularly with each other.

·

Pain

and other symptoms of terminal illness must be managed.

·

The

patient and family should be viewed as a single unit of care.

·

Home

care of the dying is necessary.

·

Bereavement

care must be provided to family members.

·

Research

and education should be ongoing.

Hospice Care in the United States

Although the concept dates to ancient times, hospice as a way of caring

for those at the end of life did not emerge in the United States until the

1960s (Hospice Association of America, 2001). The hospice movement in the

United States is based on the be-lief that meaningful living is achievable

during terminal illness, and that it is best supported in the home, free from

technologi-cal interventions to prolong physiologic dying (Amenta, 1986). After

the first U.S. hospice was founded in Connecticut in 1974, the concept quickly

spread and the number of hospice programs in the United States has grown

dramatically. In the years between 1984 and 1996, which followed the creation

of the Medicare Hospice Benefit, there was a 70-fold increase in the number of

hospices participating in Medicare (Hospice Association of America, 2001).

Despite more than 25 years of existence in the United States, hospice

remains an option for end-of-life care that has not been fully integrated into

mainstream health care. Although hospice care is available to persons with any

life-limiting condition, it has primarily been used by patients with advanced

cancer, where the disease staging and trajectory lend themselves to more

reliableprediction about the end of life (Boling & Lynn, 1998; Christakis

Lamont, 2000). Many reasons have been proposed for the re-luctance of

physicians to refer patients to hospice and the reluc-tance of patients to

accept this form of care. These include the difficulties in making a terminal

prognosis, the strong association of hospice with death, advances in “curative”

treatment options in late-stage illness, and financial pressures on health care

providers that may cause them to retain rather than refer hospice-eligible

patients. The result is that patients who could benefit from the comprehensive,

interdisciplinary support offered by hospice pro-grams frequently do not enter

hospice care until their final days (or hours) of life (Christakis &

Lamont, 2000).

Hospice is a coordinated program of interdisciplinary services provided

by professional caregivers and trained volunteers to pa-tients with serious,

progressive illnesses that are not responsive to cure. In hospice settings, the

patient and family together are the unit of care. The goal of hospice care is

to enable the patient to remain at home, surrounded by the people and objects

that have been important to him or her throughout life. Hospice care does not

seek to hasten death, nor does it encourage the prolongation of life through

artificial means. Hospice care hinges on the com-petent patient’s full or

“open” awareness of dying; it embraces a realism about death, such that the

patient and family are assisted to understand the dying process and can live

each moment as fully as possible.

Although most hospice care is provided in the patient’s own home, some

hospice programs have developed inpatient facilities or residences where

terminally ill patients without family support or those who desire inpatient

care may receive hospice services.

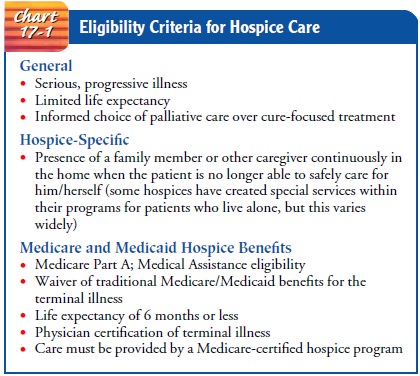

Eligibility criteria for

hospice vary depending on the hospice program, but generally patients must have

a progressive, irre-versible illness and limited life expectancy and have opted

for pal-liative care rather than cure-focused treatment. Although hospices have

historically served cancer patients, patients with any life-limiting illness

are eligible.

Medicare Hospice Benefit

In 1983, the Medicare Hospice Benefit was implemented to cover hospice

care for Medicare beneficiaries. State Medical Assistance (Medicaid) also

provides coverage for hospice care, as do most com-mercial insurers. Federal

reimbursement for hospice care ushered in a new era in hospice in which program

standards developed and published by the federal government codified what had

formerly been a grassroots, loosely organized and defined ideal for care at the

end of life. To receive Medicare dollars for hospice services, pro-grams are

required to comply with conditions of participation pro-mulgated by the Centers

for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare standards have come to largely

define hospice philosophy and services. Eligibility criteria for hospice

coverage under the Medicare Hospice Benefit are specified in Chart 17-1.

Federal rules for hospices require that the patient’s continuing eligibility

for hos-pice care is reviewed periodically. There is no limit to the length of

time that an eligible patient may continue to receive hospice care. Patients

who live longer than 6 months under hospice care are not discharged if their

physician and the hospice medical direc-tor continue to certify that the

patient is terminally ill with a life expectancy of 6 months or less, assuming

that the disease con-tinues its expected course. The hospice certification and

review process and the open-ended benefit structure are intended to ad-dress

the difficulty physicians face in predicting how long a patient will live, so

that patients are not restricted to a lifetime limit on the number of hospice

days they may receive.

To use hospice benefits under Medicare or Medicaid, the pa-tient must

meet eligibility criteria and “elect” to use the hospice benefit in place of

traditional Medicare or Medicaid benefits for the terminal illness. Once the

patient elects the benefit, the Medicare-certified hospice program assumes

responsibility for providing and paying for the care and treatment related to

the un-derlying illness for which hospice care was elected. The

Medicare-certified hospice is paid a predetermined dollar amount for each day

of hospice care each patient receives. Four levels of hospice care are covered

under Medicare and Medicaid hospice benefits:

•

Routine home care: All services provided are

included in the daily rate to the hospice.

•

Inpatient respite care: A 5-day inpatient stay,

provided on an occasional basis to relieve the family caregivers

•

Continuous care: Continuous nursing care provided

in the home for management of a medical crisis. Care reverts to the routine

home care level when the crisis is resolved. (For example, the patient develops

seizure activity and a nurse is placed in the home continuously to monitor the

patient and administer medications. After 72 hours the seizure activity is

under control, the family has been instructed how to care for the patient, and

the continuous nursing care is stopped.)

•

General inpatient care: Inpatient stay for symptom

man-agement that cannot be provided in the home; not subject to the guidelines

for a standard hospital inpatient stay.

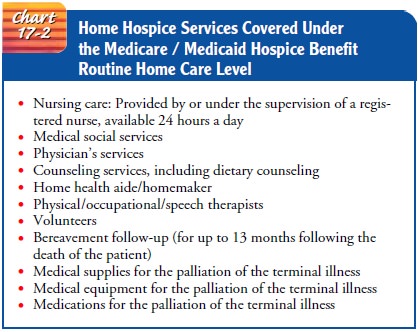

Most hospice care is provided at the “routine home care” level and

includes the services depicted in Chart 17-2. According to federal guidelines,

hospices may provide no more than 20% of the aggregate annual patient days at

the inpatient level. Patients may “revoke” their hospice benefits at any time,

resuming tradi-tional coverage under Medicare or Medicaid for the terminal

ill-ness. They may also re-elect their hospice benefits at a later time after

reassessment for eligibility according to these criteria

Related Topics