Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: End-of-Life Care

Communication - Nursing Care of the Terminally Ill Patient

COMMUNICATION

As has been discussed, remarkable strides have been made in the ability

to prolong life, but attention to care for the dying lags be-hind (Callahan,

1993b). On one level, this comes as no surprise. Each of us will eventually

face death, and most would agree that one’s own demise is a subject he or she

would prefer not to con-template. Indeed, Glaser and Strauss (1965) noted that

unwill-ingness in our culture to talk about the process of dying is tied to our

discomfort with the notion of particular deaths—those of our patients’ and our

own—rather than talking about death in the ab-stract, which is more

comfortable. Finucane (1999) observed that our struggle to stay alive is a

prerequisite to being human. Con-fronting death in our patients uncovers our

own deeply rooted fears.

To develop a level of comfort and expertise in communicat-ing with

seriously and terminally ill patients and their families, nurses and other

clinicians need to first consider their own expe-riences with and values

concerning illness and death. Reflection, reading, and talking with family

members, friends, and colleagues can assist the nurse to examine beliefs about

death and dying. Talking with individuals from differing cultural backgrounds

canassist the nurse to view personally held beliefs through a different lens,

and can help to sensitize the nurse to death-related beliefs and practices in

other cultures. Discussion with nursing and non-nursing colleagues can also be

useful to reveal the values shared by many health care professions and identify

diversity in the val-ues of patients in their care. Values clarification and

personal death awareness exercises can provide a starting point for

self-discovery and discussion.

Skills for Communicating With the Seriously Ill

Nurses need to develop skill and comfort in assessing patients’ and

families’ responses to serious illness and planning interven-tions that will

support their values and choices throughout the continuum of care. Patients and

families need ongoing assistance: telling a patient something once is not

teaching, and hearing the patient’s words is not the same as active listening.

Throughout the course of a serious illness, patients and their families will

en-counter complicated treatment decisions, bad news about disease progression,

and recurring emotional responses. In addition to the time of initial

diagnosis, lack of response to the treatment course, decisions to continue or

withdraw particular interven-tions, and decisions about hospice care are

examples of critical points on the treatment continuum that demand patience,

em-pathy, and honesty from the nurse. Discussing sensitive issues such as

serious illness, hopes for survival, and fears associated with death is never easy.

However, the art of therapeutic communica-tion can be learned and, like other

skills, must be practiced to gain expertise. Similar to other skills,

communication should be prac-ticed in a “safe” setting, such as a classroom or

clinical skills lab-oratory with other students or clinicians.

Although communication

with each patient and family should be tailored to their level of understanding

and values concerning disclosure, general guidelines for the nurse include the

following (Addington, 1991):

· Deliver and interpret

the technical information necessary for making decisions without hiding behind

medical termi-nology.

· Realize that the best

time for the patient to talk may be when it is least convenient for you.

· Being fully present

during any opportunity for communi-cation is often the most helpful form of

communication.

· Allow the patient and

family to set the agenda regarding the depth of the conversation.

Nursing Interventions When the Patient and Family Receive Bad News

Communicating about a life-threatening diagnosis or about dis-ease

progression is best accomplished by the interdisciplinary team in any setting—a

physician, nurse, and social worker should be present whenever possible to

provide information, facilitate dis-cussion, and address concerns. Most

importantly, the presence of the team conveys caring and respect for the

patient and family. Creating the right setting is particularly important. If

the patient wishes to have family present for the discussion, arrangements

should be made to have the discussion at a time that is best for the patient

and family. A quiet area with a minimum of disturbances should be used. Each

clinician who is present should turn off beep-ers or other communication

devices for the duration of the meet-ing and should allow sufficient time for

the patient and family to absorb and respond to the news. Finally, the space in

which the meeting takes place should be conducive to seating all of the

par-ticipants at eye level. It is difficult enough for patients and fami-lies

to be the recipients of bad news without having an array of clinicians standing

uncomfortably over them at the foot of the pa-tient’s bed.

After an initial

discussion of a life-threatening illness or pro-gression of a disease, patients

and their families will have many questions and may need to be reminded of

factual information. Coping with news about a serious diagnosis or poor

prognosis is an ongoing process. The nurse needs to be sensitive to these

on-going needs and may need to repeat previously provided infor-mation or

simply be present while the patient and family react emotionally. The most

important intervention the nurse can pro-vide is listening empathetically.

Seriously ill patients and their families need time and support to cope with

the changes brought about by serious illness and the prospect of impending

death. The nurse who is able to sit comfortably with another’s suffering, time

and time again, without judgment and without the need to solve the patient’s

and family’s problems provides an intervention that is a gift beyond measure.

Keys to effective listening include the following:

· Resist the impulse to

fill the “empty space” in communica-tion with talk.

· Allow the patient and

family sufficient time to reflect and respond after asking a question.

· Prompt gently: “Do you

need more time to think about this?”

· Avoid distractions

(noise, interruptions).

· Avoid the impulse to

give advice.

· Avoid canned responses:

“I know just how you feel.”

· Ask questions.

· Assess

understanding—your own and the patient’s—by re-stating, summarizing, and

reviewing.

Responding With Sensitivity To Difficult Questions

Patients will often direct questions or concerns to nurses before they

have been able to fully discuss the details of their diagnosis and prognosis

with the physician or the entire health care team. Using open-ended questions

allows the nurse to elicit the pa-tient’s and family’s concerns, explore

misconceptions and needs for information, and form the basis for collaboration

with the physician and other team members. For example, the seriously ill

patient may ask the nurse, “Am I dying?” The nurse should avoid making

unhelpful responses that dismiss the patient’s real con-cerns or defer the

issue to another care provider. Nursing assess-ment and intervention are always

possible, even when a need for further discussion with the physician is clearly

indicated. When-ever possible, discussions in response to the patient’s

concerns should occur when the patient expresses a need, although it may be the

least convenient time for the nurse (Addington, 1991). Creating an

uninterrupted space of just 5 minutes can do much to identify the source of the

concern, allay anxieties, and plan for follow-up. For example, in response to

the question, “Am I dying?” the nurse could establish eye contact and follow

with a statement acknowledging the patient’s fears (“This must be very

difficult for you”) and an open-ended statement or question (“Tell me more

about what is on your mind.”). The nurse then needs to listen intently, ask

additional questions for clarification, and provide reassurance only when it is

realistic. In this example,

As

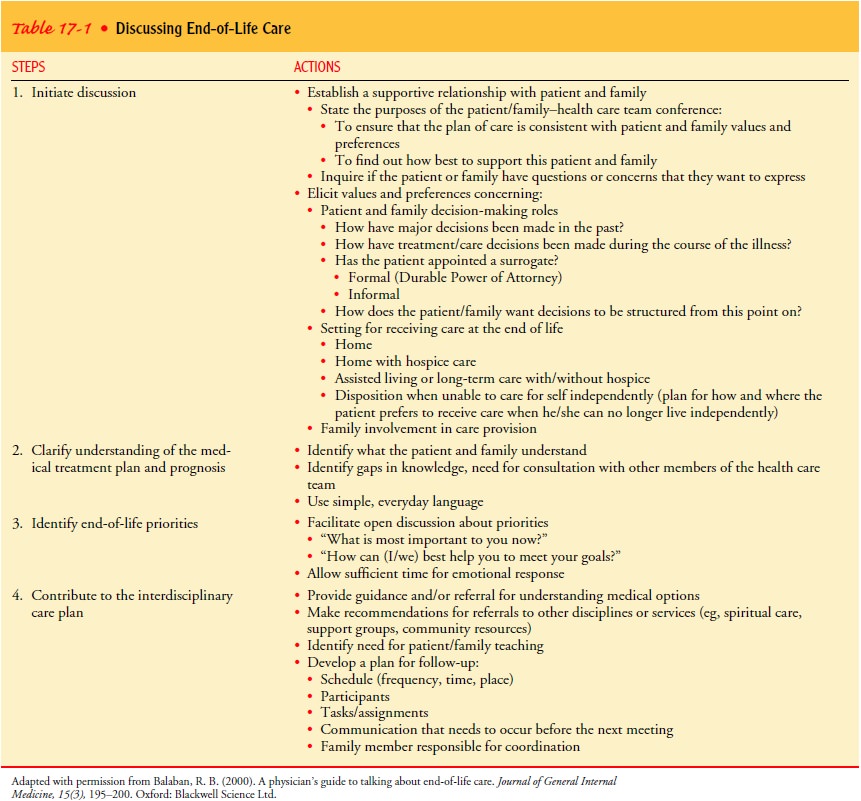

a member of the interdisciplinary team caring for the pa-tient at the end of

life, the nurse fills an important role in facili-tating the team’s

understanding of the patient’s values and preferences, the family dynamics

concerning decision making, and the patient’s and family’s response to

treatment and chang-ing health status. Many dilemmas in patient care at the end

of life are related to poor communication between team members and the patient

and family and failure of team members to commu-nicate effectively with each

other. Regardless of the care setting, the nurse can ensure a proactive

approach to the psychosocial care of the patient and family. Periodic,

structured assessments pro-vide an opportunity for all parties to consider

their priorities and plan for an uncertain future. The nurse can assist the

patient and family to clarify their values and preferences concerning

end-of-life care by using a structured approach. Sufficient time must be

devoted to each step, so that the patient and family have time to process new

information, formulate questions, and consider their options. The nurse may

need to plan several meetings to accom-plish the four steps described in Table

17-1.

Related Topics