Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: End-of-Life Care

Managing Physiologic Responses to Illness - Nursing Care of the Patient

MANAGING PHYSIOLOGIC RESPONSES TO ILLNESS

Patients

approaching the end of life experience many of the same symptoms, regardless of

their underlying disease processes. Symp-toms in terminal illness may be caused

by the disease, either di-rectly (eg, dyspnea due to chronic obstructive lung

disease) or indirectly (eg, nausea and vomiting related to pressure in the

gastric area), by the treatment for the disease, or by a coexisting disorder

that is unrelated to the disease.

The

goals of symptom management at the end of life are to completely relieve the

symptom when possible, or to decrease the symptom to a level that the patient

can tolerate when it cannot be completely relieved. Medical interventions may

be aimed at treat-ing the underlying causes of the symptoms. Pharmacologic and

nonpharmacologic methods for symptom management may be used in combination with

medical interventions to modify the physiologic causes of symptoms. For

example, some patients who develop pleural effusion secondary to metastatic

cancer may ex-perience temporary relief of the associated dyspnea following

thoracentesis, an invasive medical procedure in which fluid is drained from the

pleural space. In addition, pharmacologic man-agement with low-dose oral

morphine is very effective in relieving dyspnea, and guided relaxation may

reduce the anxiety associated with the sensation of breathlessness. As with

pain, the principles of pharmacologic symptom management are the smallest dose

of the medication to achieve the desired effect, avoidance of poly-pharmacy,

anticipation and management of medication side ef-fects, and creation of a

therapeutic regimen that is acceptable to the patient based on his or her goals

for maximizing quality of life.

As

with pain management, patients may elect to tolerate higher symptom levels in

exchange for greater independence, mobility, alertness, or other priorities.

Anticipating and planning interven-tions for symptoms that have not yet

occurred is a cornerstone of end-of-life care. Both patients and family members

cope more ef-fectively with new symptoms and exacerbations of existing

symp-toms when they know what to expect and how to manage it. Hospice programs

typically provide “emergency kits” containing ready-to-administer doses of a

variety of medications that are use-ful to treat symptoms in advanced illness.

Family members can be instructed to administer a prescribed dose from the

emergency kit, often avoiding prolonged suffering for the patient as well as

re-hospitalization for symptom management.

Pain

Pain

and suffering are among the most feared consequences of cancer (Roth &

Breitbart, 1996). Pain is a significant symptom for many cancer patients

throughout their treatment and disease course; it results both from the disease

and the modalities used to treat it. Numerous studies have indicated that

patients with ad-vanced illness, particularly cancer, experience considerable

pain (Field & Cassel, 1997; Jacox, Carr, & Payne, 1994). While the

means to relieve pain have existed for many years, the continued, pervasive

undertreatment of pain has been well documented (American Pain Society, 1999;

Jacox et al., 1994). It is estimated that as many of 70% of patients with

advanced cancer experience severe pain (Jacox et al., 1994; World Health

Organization, 1990). The impact of poorly managed pain on patients’

psychological, emotional, social, and financial well-being has attracted

con-siderable research interest, but practice has been slow to change (Spross,

1992).

Patients

who have an established regimen of analgesics should continue to receive those

medications as they approach the end of life. Inability to communicate pain

should not be equated with the absence of pain. While most pain can be managed

effectively using the oral route, as the end of life nears patients may be less

able to swallow oral medications due to somnolence or nausea. Patients who have

been receiving opioids should continue to re-ceive equianalgesic doses via the

rectal or sublingual routes. Con-centrated morphine solution can be very

effectively delivered by the sublingual route, as the small liquid volume is

well tolerated even when the patient cannot swallow. As long as the patient

con-tinues to receive opioids, a regimen to combat constipation must be

implemented. If the patient cannot swallow laxatives or stool softeners, rectal

suppositories or enemas may be necessary.

The

nurse should teach the family about continuation of com-fort measures as the

patient approaches the end of life, how to ad-minister analgesics via alternate

routes, and how to assess for pain when the patient cannot verbally report pain

intensity. Because the analgesics administered orally or rectally are

short-acting, typically scheduled as frequently as every 3 to 4 hours around

the clock, there is always a strong possibility that the patient approaching

the end of life will die in close proximity to the time of analgesic

ad-ministration. If the patient is at home, family members adminis-tering

analgesics need to be prepared for this possibility. They will need reassurance

that they did not “cause” the death of the patient by administering a dose of

analgesic medication (see Chart 13-3).

Dyspnea

Dyspnea

is an uncomfortable awareness of breathing that is common in patients

approaching the end of life (Brant, 1998). Dyspnea is a highly subjective

symptom that often is not associ-ated with visible signs of distress, such as

tachypnea, diaphoresis, or cyanosis. Patients with primary lung tumors, lung

metastases, pleural effusion, and restrictive lung disease may experience

sig-nificant dyspnea. Although the underlying cause of the dyspnea can be

identified and treated in some cases, the burdens of addi-tional diagnostic evaluation

and treatment aimed at the physio-logical problem may outweigh the benefits.

The treatment of dyspnea varies depending on the patient’s general physical

con-dition and imminence of death. For example, a blood transfusion may provide

temporary symptom relief for the anemic patient earlier in the disease process;

however, as the patient approaches the end of life the benefits are typically

short-lived or absent.

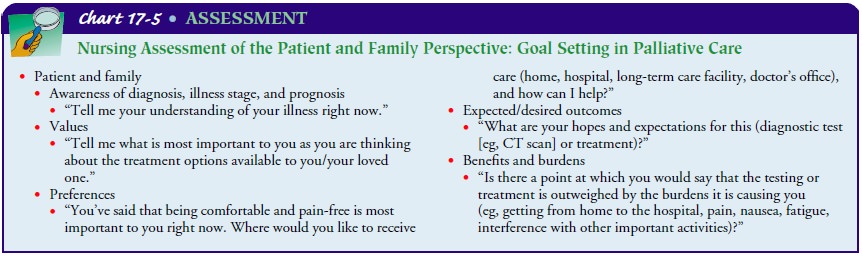

NURSING ASSESSMENT AND INTERVENTION

As

is true in pain assessment and management, the patient’s re-port of dyspnea

must be believed. Also like the experience of physical pain, the meaning of the

dyspnea to the patient may in-crease his or her suffering. For example, the

patient may interpret increasing dyspnea as a sign that death is approaching.

For some patients, sensations of breathlessness may invoke frightening im-ages

of drowning or suffocation, and the resulting cycle of fear and anxiety may

create even greater sensations of breathlessness. Therefore, the nurse should

conduct a careful assessment of the psychosocial and spiritual components of

the symptom (see Chart 17-5). Physical assessment parameters include:

·

Symptom intensity, distress, and

interference with activities (scale of 0 to 10)

·

Auscultation of lung sounds

·

Assessment of fluid balance

·

Measurement of dependent edema

(circumference of lower extremities)

·

Measurement of abdominal girth

·

Temperature

·

Skin color

·

Sputum quantity and character

·

Cough

To

determine the intensity of the symptom and its interference with daily activities,

patients can be asked to self-report using a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is no

dyspnea and 10 is the worst imag-inable dyspnea. Measurement of the patient’s

baseline before treatment and subsequent measures during exacerbation of the

symptom, periodically during treatment, and whenever the treat-ment plan

changes will provide ongoing objective evidence for the efficacy of the

treatment plan. In addition, physical assessment findings may assist in

locating the source of the dyspnea and se-lecting nursing interventions to

relieve the symptom. The com-ponents of the assessment will change as the

patient’s condition changes. For example, when the patient who has been on

daily weights can no longer get out of bed, the goal of comfort may out-weigh

the benefit of continued weights. Like other symptoms at the end of life,

dyspnea can be managed effectively in the absence of assessment and diagnostic

data (ie, arterial blood gases) that are standard when the patient’s illness or

symptom is reversible.

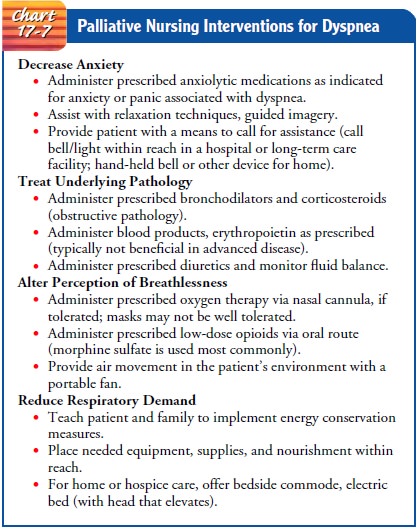

Nursing

management of dyspnea at the end of life is directed toward administering

medical treatment for the underlying pathol-ogy, monitoring the patient’s

response to treatment, assisting the patient and family to manage anxiety

(which exacerbates dyspnea),altering the perception of the symptom, and

conserving energy (Chart 17-7). Pharmacologic intervention is aimed at

modifying lung physiology and improving performance as well as altering the

perception of the symptom. Bronchodilators and cortico-steroids are examples of

medications used to treat underlying ob-structive pathology, thereby improving

overall lung function. Low doses of opioids are very effective in relieving

dyspnea, although the mechanism of relief is not entirely clear. Although

dyspnea in terminal illness is typically not associated with dimin-ished blood

oxygen saturation, low-flow oxygen often provides psychological comfort to the

patient and the family, particularly in the home setting.

As

discussed above, dyspnea may be exacerbated by anxiety, and anxiety may trigger

episodes of dyspnea, setting off a respi-ratory crisis in which patient and

family may panic. For patients receiving care at home, patient and family

instruction should in-clude anticipation and management of crisis situations and

a clearly communicated emergency plan. Patients and families should be

instructed about medication administration, condition changes that should be

reported to the physician and nurse, and strategies for coping with diminished

reserves and increasing symptomatology as the disease progresses. The patient

and fam-ily need reassurance that the symptom can be effectively managed at

home without the need for activation of the emergency med-ical services or

hospitalization and that a nurse will be available at all times via telephone

or to conduct a visit.

Nutrition and Hydration at the End of Life

ANOREXIA

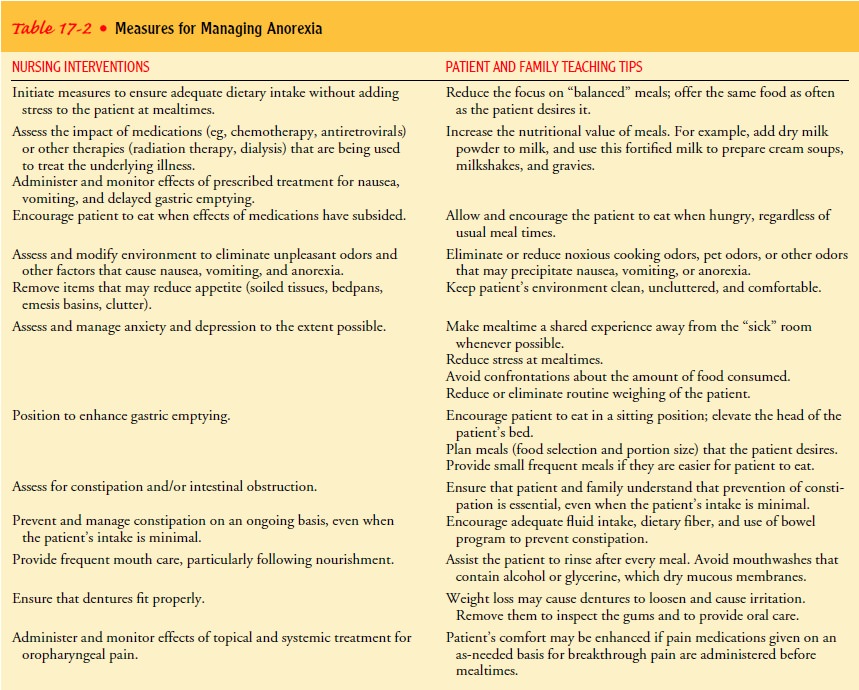

Anorexia and cachexia are common problems in the seriously ill. The profound changes in the patient’s appearance and his or her concomitant lack of interest in the socially important rituals of mealtime are particularly disturbing to families.

The approach to the problem varies depending on the

patient’s stage of illness, level of disability associated with the illness,

and desires. The anorexia-cachexia syndrome is characterized by disturbances in

carbohydrate, protein, and fat metabolism, endocrine dysfunc-tion, and anemia.

The syndrome results in severe asthenia (loss of energy). Although causes of

anorexia may be controlled for a pe-riod of time, progressive anorexia is an

expected and natural part of the dying process. Anorexia may be related to or

exacerbated by situational variables (eg, the ability to have meals with the

fam-ily versus eating alone in the “sick room”), progression of the dis-ease,

treatment for the disease, or psychological distress. The patient and family

should be instructed in strategies to manage the variables associated with

anorexia. Table 17-2 summarizes nursing measures and patient and family

teaching for managing anorexia.

USE OF PHARMACOLOGIC AGENTS TO STIMULATE APPETITE IN THE TERMINALLY ILL

A

number of pharmacologic agents are commonly used to stim-ulate appetite in

anorectic patients. Commonly used medications for appetite stimulation include

dexamethasone (Decadron), cypro-heptadine (Periactin), megestrol acetate

(Megace), and dronabi-nol (Marinol). Dexamethasone initially increases appetite

and may provide short-term weight gain in some patients. However, therapy may

need to be discontinued in the patient with a longer life expectancy, as after

3 to 4 weeks corticosteroids interfere with the synthesis of muscle protein.

Cyproheptadine may be used when corticosteroids are contraindicated, such as

when the pa-tient is diabetic. It promotes mild appetite increase but no

ap-preciable weight gain. Megestrol acetate produces temporary weight gain of

primarily fatty tissue, with little effect on protein balance. Because of the

time required to see any effect from this agent, therapy should not be

initiated if life expectancy is less than 30 days. Finally, dronabinol is a

psychoactive compound found in cannabis that may be helpful in reducing nausea

and vomiting, appetite loss, pain, and anxiety, thereby improving intake in

some patients. However, dronabinol is not as effective as the other agents for

appetite stimulation in most patients. Although the use of these agents may

cause temporary weight gain, their use is not associated with an increase in

lean body mass in the terminally ill. Therapy should be tapered or discontinued

after 4 to 8 weeks if there is no response (Wrede-Seaman, 1999).

CACHEXIA

Cachexia

refers to severe muscle wasting and weight loss associated with illness.

Although anorexia may exacerbate cachexia, it is not the primary cause. Cachexia

is associated with changes in metab-olism that include hypertriglyceridemia,

lipolysis, and accelerated protein turnover, leading to depletion of fat and

protein stores (Plata-Salaman, 1997). However, the pathophysiology of cachexia

in terminal illness is not well understood. In terminal illness, the severity

of tissue wasting is greater than would be expected from reduced food intake

alone, and typically increasing appetite or food intake does not reverse

cachexia in the terminally ill.

Anorexia and cachexia differ from starvation (simple food deprivation) in several important ways. Appetite is lost early in the process, the body becomes catabolic in a dysfunctional way, and supplementation by gastric feeding (tube feeding) or par-enteral nutrition in advanced disease does not replenish lost lean body mass. At one time it was believed that cancer patients with rapidly growing tumors developed cachexia because the tumor created an excessive nutritional demand and diverted nutrients from the rest of the body.

Recent research links cy-tokines produced by the body in response to

a tumor to a com-plex inflammatory-immune response present in patients whose

tumors have metastasized, leading to anorexia, weight loss, and altered

metabolism. An increase in cytokines occurs not only in cancer but also in AIDS

and many other chronic diseases (Plata-Salaman, 1997).

ARTIFICIAL NUTRITION AND HYDRATION IN TERMINAL ILLNESS

Along

with breathing, eating and drinking are essential to survival throughout one’s

lifetime. As patients near the end of life, their bodies’ nutritional needs

change, their desire for food and fluid may diminish, and they may no longer be

able to use, eliminate, or store nutrients and fluids adequately. Eating,

feeding, and shar-ing meals are important social activities in families and

commu-nities, and food preparation and enjoyment are linked to happy memories,

strong emotions, and hopes for survival. For the patient with serious illness,

food preparation and mealtimes often become battlegrounds where well-meaning

family members argue, plead, and cajole to encourage the ill person to eat. It

is not unusual for seriously ill patients to lose their appetites entirely, to

develop strong aversions for foods they have enjoyed in the past, or to crave a

particular food to the exclusion of all other foods.

Although

nutritional supplementation may be an important part of the treatment plan in

early or chronic illness, unintended weight loss and dehydration are expected

sequelae of progressive illness. As illness progresses, patients, families, and

clinicians may believe that without artificial nutrition and hydration, the

termi-nally ill patient will “starve,” causing profound suffering and has-tened

death. However, starvation should not be viewed as the failure to implant tubes

for nutritional supplementation or hy-dration of terminally ill patients with

irreversible progression of disease. Studies have demonstrated that terminally

ill patients who were hydrated had neither improved biochemical parame-ters nor

improved states of consciousness (Waller, Hershkowitz Adunsky, 1994).

Similarly, survival was not increased when terminally ill patients with

advanced dementia received enteral feeding (Meier, Ahronheim, Morris et al.,

2001). Further, in pa-tients who are close to death there are beneficial

effects to with-holding or withdrawing artificial nutrition and hydration, such

as decreased urine output and incontinence, decreased gastric flu-ids and

emesis, decreased pulmonary secretions and respiratory distress, and decreased

edema and pressure discomfort (Zerwekh, 1987).

As

the patient approaches the end of life, families and health care providers

should offer the patient what he or she desires and can most easily tolerate.

Nurses should instruct the family how to separate feeding from caring by

demonstrating love, sharing, and caring by being with the loved one in other

ways. Preoccupation with appetite, feeding, and weight loss diverts energy and

time that the patient and family could use in other meaningful activi-ties. The

following are tips to promote nutrition for the termi-nally ill patient:

·

Offer small portions of favorite

foods.

·

Do not be overly concerned about a

“balanced” diet.

·

Cool foods may be better tolerated

than hot foods.

·

Offer cheese, eggs, peanut butter,

mild fish, chicken, or turkey. Meat (especially beef) may taste bitter and

unpleasant.

·

Add milkshakes, “Instant Breakfast”

drinks, or other liquid supplements.

·

Add dry milk powder to milkshakes

and cream soups to in-crease protein and calorie content.

·

Place nutritious foods at the

bedside (fruit juices, milk-shakes in insulated drink containers with straws).

·

Schedule meals when family members

can be present to provide company and stimulation.

·

Avoid arguments at mealtime.

·

Assist the patient to maintain a

schedule of oral care. Rinse the mouth after each meal or snack. Avoid

mouthwashes that contain alcohol. Use a soft toothbrush. Treat ulcers or

lesions. Make sure dentures fit well.

·

Treat pain and other symptoms.

·

Offer ice chips made from frozen

fruit juices.

·

Allow the patient to refuse foods

and fluids.

Delirium

Many

patients may remain alert, arousable, and able to commu-nicate until very close

to death. Others may sleep for long inter-vals and awaken only intermittently,

with eventual somnolence until death. Delirium refers to concurrent

disturbances in level of consciousness, psychomotor behavior, memory, thinking,

atten-tion, and sleep-wake cycle (Brant, 1998). In some patients, a pe-riod of

agitated delirium may precede death, sometimes causing families to be hopeful

that the suddenly active patient may be get-ting better. Confusion may be

related to underlying, treatable conditions such as medication side effects or

interactions, pain or discomfort, hypoxia or dyspnea, a full bladder or

impacted stool. In patients with cancer, confusion may be secondary to brain

metastases. Delirium may also be related to metabolic changes, infection, and

organ failure.

The

patient with delirium may become hypoactive or hyper-active, restless,

irritable, and fearful. Sleep deprivation and hal-lucinations may occur. If

treatment of the underlying factors contributing to these symptoms bring no

relief, a combination of pharmacologic intervention with neuroleptics or benzodiazepines

may be effective in decreasing distressing symptoms. Haloperidol (Haldol) may

reduce hallucinations and agitation. Benzodiazepines (eg, lorazepam [Ativan])

can reduce anxiety but will not clear the sensorium and may contribute to

worsening cognitive impair-ment if used alone.

Nursing

interventions are aimed at identifying the underlying causes of delirium,

acknowledging the family’s distress over its oc-currence, reassuring them about

what is normal, teaching the family how to interact with and ensure safety for

the patient with delirium, and monitoring the effects of medications used to

treat severe agitation, paranoia, or fear. Confusion may mask the patient’s

unmet spiritual needs and fears about dying. Spiritual inter-vention, music

therapy, gentle massage, and therapeutic touch may provide some relief.

Reducing environmental stimuli, avoiding harsh lighting or very dim lighting

(which may produce disturbing shadows), the presence of familiar faces, and

gentle reorientation and reassurance are also helpful.

Depression

Clinical

depression should not be accepted as an inevitable con-sequence of dying, nor

should it be confused with sadness and an-ticipatory grieving, which are normal

reactions to the losses associated with impending death. Emotional and

spiritual sup-port and control of disturbing physical symptoms are appro-priate

interventions for situational depression associated with terminal illness. The

psychological sequelae of cancer pain have been linked to suicidal thought and

less frequently to carrying out a planned suicide (Ripamonti, Filiberti, Totis

et al., 1999). Can-cer patients with advanced disease are especially vulnerable

to delirium, depression, suicidal ideation, and severe anxiety (Roth

Breitbart,

1996). Higher levels of debilitation predict higher levels of pain and

depressive symptoms, and the presence of pain doubles the likelihood of

developing major psychiatric complica-tions of illness (Roth & Breitbart,

1996). Patients and their fam-ilies must be given space and time to experience

sadness and to grieve, but patients should not have to endure untreated

depres-sion at the end of their lives. An effective combined approach to

clinical depression includes relief of physical symptoms, attention to

emotional and spiritual distress, and pharmacologic inter-vention with

psychostimulants, selective serotonin reuptake in-hibitors (SSRIs), and

tricyclic antidepressants (Block, 2000).

Related Topics