Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: End-of-Life Care

Nursing Care of the Patient Who Is Close to Death

Nursing Care of the Patient Who Is Close to

Death

Providing

care to the patient who is close to death and being present at the time of

death can be one of the most rewarding ex-periences a nurse can have. Patients

and their families are under-standably fearful of the unknown, and the approach

of death may prompt new concerns or cause previous fears or issues to

resur-face. It has often been said that as we age and as we approach death, we

do not become different people, just more like our-selves. Families that have

always had difficulty communicating or in which there are old resentments and

hurts may experience heightened difficulty as their loved one nears death. In

contrast, the time at the end of life can also afford the family the

opportu-nity to resolve old hurts and learn new ways of being a family.

Regardless of the setting, dying patients can be made comfort-able, space can

be made for their loved ones to remain present when they wish, and the

opportunity to experience growth and healing can be facilitated by skilled

practitioners. Likewise, regard-less of setting, patients’ and families’

apprehension surrounding the time of death may be diminished if they know what

to expect as death nears and how to respond.

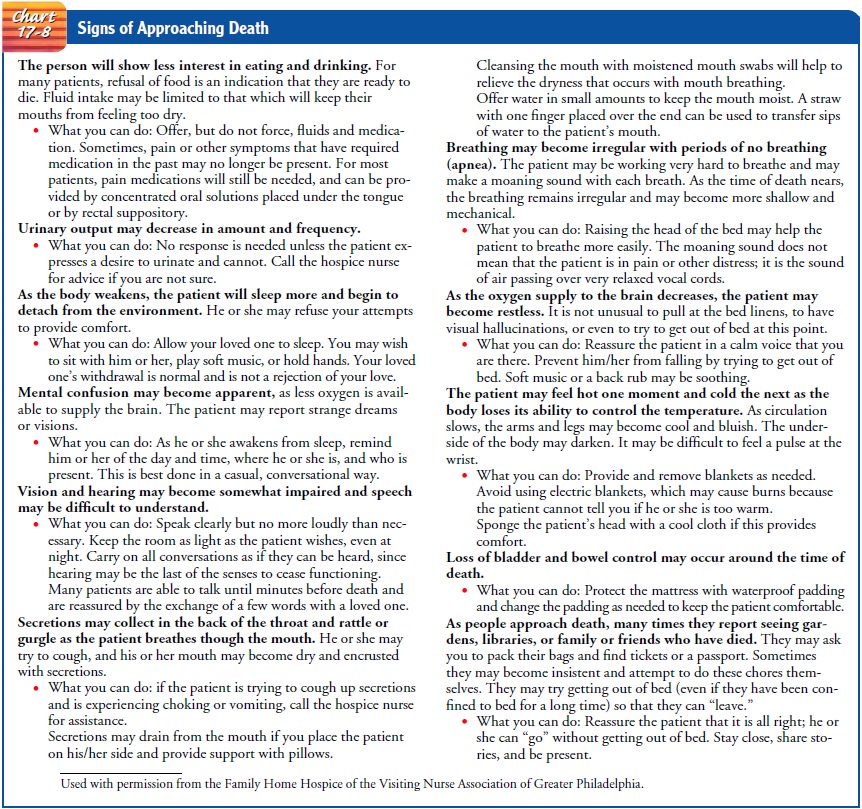

EXPECTED PHYSIOLOGIC CHANGES WHEN THE PATIENT IS CLOSE TO DEATH

Observable,

expected changes in the body take place as the pa-tient approaches death and

organ systems begin to fail. Nursing care measures aimed at patient comfort

should be continued: pain medications (administered rectally or sublingually),

turning, mouth care, eye care, positioning to facilitate draining of

secre-tions, and measures to protect the skin from incontinence should be

continued. The nurse should consult with the physician about discontinuing

measures that no longer contribute to patient com-fort such as drawing blood,

administering tube feedings, suc-tioning (in most cases), and invasive

monitoring. The nurse should prepare the family for the normal, expected

changes that accompany the period immediately preceding death. Although the

exact time of death cannot be predicted, it is often possible to identify when

a patient is very close to death. Hospice programs frequently provide written

information for families so they know what to expect and what to do as death

nears (Chart 17-8).

If

they have been prepared for the time of death, families are less likely to

panic and will be better able to be with their loved one in a meaningful way.

Noisy, gurgling breathing or moaning is generally most distressing to the

family. In most cases, the sounds of breathing at the end of life are related

to oropharyngeal relaxation and diminished awareness. Family members may have

difficulty believing that the patient is not in pain or that his or her

breathing could not be improved by suctioning secretions. Pa-tient positioning

and family reassurance are the most helpful re-sponses to these symptoms.

Terminal “Bubbling”

When

death is imminent, the patient may become increasingly somnolent and unable to

clear sputum or oral secretions, which may lead to further impairment of

breathing from pooled and/or dried and crusted secretions. The sound and

appearance of the se-cretions are often more distressing to the family than is

the pres-ence of the secretions to the patient. Family distress over the

changes in patient condition may be eased by supportive nursing care. Continuation

of comfort-focused interventions and reas-surance that the patient is not in

any distress can do much to ease family concerns. Gentle mouth care with a

moistened swab or very soft toothbrush will help to maintain the integrity of

the pa-tient’s mucous membranes. In addition, gentle oral suctioning,

positioning to enhance drainage of secretions, and sublingual or transdermal

administration of anticholinergic drugs (Table 17-3) to reduce the production

of secretions will provide comfort to the patient and support to the family.

Deeper suctioning may cause significant discomfort to the dying patient and is

rarely of any benefit, as secretions will reaccumulate rapidly.

THE DEATH VIGIL

Although

every death is unique, it is often possible for the expe-rienced clinician to

assess that the patient is “actively” or immi-nently dying and to prepare the

family in the final days or hours leading to death. As death nears, the patient

may withdraw, sleep for longer intervals, or become somnolent. The family should

be encouraged to be with the patient, to speak and reassure him or her of their

presence, to stroke or touch him or her, or to lie alongside him or her (even

in the hospital or long-term care fa-cility) if they are comfortable with this

degree of closeness and can do so without causing discomfort to the patient.

Family

members may have gone to great lengths to ensure that their loved one will not

die alone. However, despite the best intentions and efforts of families and

clinicians, the patient’s death may occur at a time when no one is present. In

any setting, it is unrealistic for family members to be at the patient’s

bedside 24 hours a day, and it is not unusual for patients to die when the

family has stepped away from the bedside just briefly. Experi-enced hospice

clinicians have observed and reported that some patients appear to “wait” until

family members are away from the bedside to die, perhaps to spare their loved

ones the pain of being present at the time of death. The nurse can reassure family

mem-bers throughout the death vigil by being present intermittently or

continuously, modeling behaviors (such as touching and speak-ing to the

patient), providing encouragement in relation to fam-ily caregiving, providing

reassurance about normal physiologic changes, and encouraging family rest

breaks. When the patient dies while the family is away from the bedside, the

family may ex-press feelings of guilt and profound grief and will need

emotional support.

AFTER-DEATH CARE

The time of death is generally preceded by a period of gradual diminishment of bodily functions in which increasing intervals between respirations, a weakened and irregular pulse, diminish-ing blood pressure, and skin color changes or mottling may be observed. For the patient who has received adequate manage-ment of symptoms and for the family who has received adequate preparation and support, the actual time of death is commonly peaceful and occurs without struggle. The nurse may or may not be present at the time of the patient’s death. In many states, the certifying physician may authorize the nurse to make the pro-nouncement of death and sign the death certificate. The determi-nation of death is made through a physical examination that includes auscultation for the absence of breathing and heart sounds. Home care or hospice programs in which the nurse makes the time-of-death visit and pronouncement of death will have po-lices and procedures to guide the nurse’s actions during this visit. Immediately upon cessation of vital functions the body will begin to change. The body will become dusky or bluish, waxen-appear-ing, and cool, blood will darken and pool in dependent areas of the body (such as the back and sacrum if the body is in a supine position), and urine and stool may be evacuated.

Immediately

following the death, the family should be al-lowed and encouraged to spend time

with the deceased. Normal responses of

family members at the time of death vary widely and range from quiet expressions

of grief to overt ex-pressions that include wailing and prostration. Families’

desires for privacy during their time with the deceased should be hon-ored.

Family members may wish to independently manage or assist with care of the body

after death. If the death occurs in a long-term care facility, the nurse

follows the facility’s procedure for preparation of the body and transportation

to the facility’s morgue. However, the family’s needs to remain with the

de-ceased, to wait until other family members arrive before the body is moved,

and to perform after-death rituals should be honored. When an expected death

occurs in the home setting, the body is often transported directly to the

funeral home by the funeral director.

GRIEF, MOURNING, AND BEREAVEMENT

A

wide range of feelings and behaviors are normal, adaptive, and healthy

reactions to the loss of a loved one. Grief

refers to the personal feelings that accompany an anticipated or actual loss. Mourning reflects the individual,

family, group, and cul-tural expressions of grief and associated behaviors. Bereave-ment refers to the period of

time during which mourning takesplace. Both grief reactions and mourning

behaviors change over time as the individual learns to live with the loss.

Although the pain of the loss may be tempered by the passage of time, recent

conceptualizations of loss as an ongoing developmental process maintain that

time does not heal the bereaved individual com-pletely (Silverman, 2001); that

is, the bereaved do not get over a loss entirely, nor do they return to who

they were before the loss. Rather, they develop a new sense of who they are and

where they fit in a world that has changed dramatically and permanently.

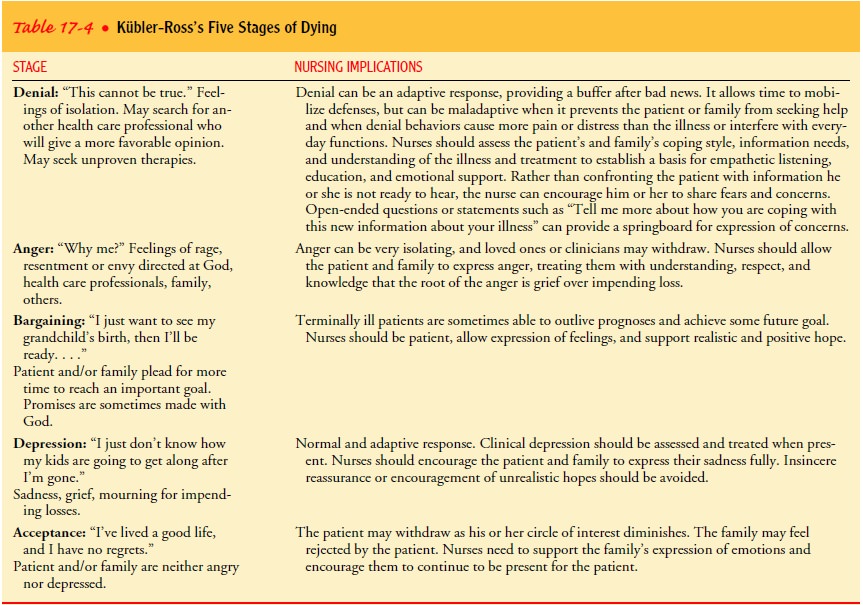

Anticipatory Grief and Mourning

Denial,

sadness, anger, fear, and anxiety are normal grief reactions in the individual

with life-threatening illness and those close to him or her. Kübler-Ross (1969)

described five common emotional reactions to dying that are applicable to the

experience of any loss (Table 17-4). Although useful in understanding the

overall expe-rience of the dying process, the stages that Kübler-Ross described

have been misinterpreted as following a linear, expected trajectory. Not every

patient or family member experiences every stage, many patients never reach a

stage of acceptance, and patients and fami-lies fluctuate on a sometimes

day-to-day basis in their emotional responses. Further, while impending loss

stresses the patient, those who are close to him or her, and the functioning of

the family unit, awareness of dying also provides a unique opportunity for

family members to reminisce, resolve relationships, plan for the future, and

say goodbye.

Individual and family coping with the anticipation of death is complicated by the varied and conflicting trajectories that grief and mourning may assume in the family. For example, while the patient may be experiencing sadness while contemplating role changes that have been brought about by the illness, the patient’s spouse or partner may be expressing or holding in feelings of anger about the current changes in role and impending loss of the relationship; others in the family may be engaged in denial (eg, “Dad will get better; he just needs to eat more.”), fear (“Who will take care of us?” or “Will I get sick too?”), or profound sadness and withdrawal. Although each of these behaviors is normal, ten-sion may arise when one or more family members perceive that others are less caring, too emotional, or too detached.

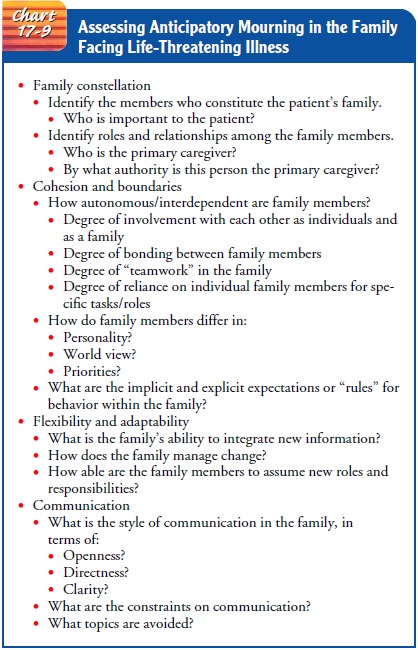

The

nurse needs to assess the characteristics of the family sys-tem and intervene

in a manner that supports and enhances the cohesion of the family unit.

Parameters for assessing the family facing life-threatening illness are

identified in Chart 17-9. The nurse can patiently guide family members to talk

about their feel-ings and understand them in the broader context of

anticipatory grief and mourning. Acknowledging and expressing feelings,

con-tinuing to interact with the patient in meaningful ways, and plan-ning for

the time of death and bereavement are adaptive family behaviors. Professional

support provided by grief counselors in the community, at a local hospital, in

the long-term care facility, or associated with a hospice program can help both

the patient and family to sort out and acknowledge feelings and make the end of

life as meaningful as possible.

Grief and Mourning After Death

When a loved one dies, the family members enter a new phase of grief and mourning as they begin to accept the loss, feel the pain of permanent separation, and prepare to live a life without the de-ceased. Even if the loved one died after a long illness, preparatory grief experienced during the terminal illness will not preclude the grief and mourning that follow the death.

Following the patient’s death after a long

or difficult illness, family members may expe-rience conflicting feelings of

relief that the loved one’s suffering has ended, compounded by guilt and grief

related to unresolved issues or the circumstances of death. Grief work may be

especially difficult if the patient’s death was painful, prolonged,

accompa-nied by unwanted interventions, or unattended. Families who had no

preparation or support during the period of imminence and death may have a more

difficult time finding a place for the painful memories.

Although

some family members may experience prolonged or complicated mourning, most

grief reactions fall within a “normal” range. The feelings are often profound,

but the bereaved individ-ual eventually reconciles the loss and finds a way to

re-engage with his or her life. Grief and mourning are affected by individual

char-acteristics, coping skills, and experiences with illness and death; the

nature of the relationship to the deceased; factors surrounding the illness and

the death; family dynamics; social support; and cultural expectations and

norms. After-death rituals, including preparation of the body, funeral

practices, and burial rituals, are socially and culturally significant ways

that members of a family begin to accept the reality and finality of death.

Preplanning of funerals is becom-ing increasingly common, and hospice

professionals in particular assist families to make plans for death, often

involving the patient who may wish to take an active planning role. Preplanning

the fu-neral relieves the family of the decision burden in the intensely

emotional period following a death. Uncomplicated grief and mourning are

characterized by emotional feelings of sadness, anger, guilt, and numbness;

physical sensations such as hollowness in the stomach and tightness in the

chest, weakness, and lack of energy; cognitions that include preoccupation with

the loss and a sense of the deceased as still present; and behaviors such as

crying, visiting places that are reminders of the deceased, social withdrawal,

and restless overactivity (Worden, 1991).

In

general, the period of mourning is an adaptive response to loss during which

the mourner comes to accept the loss as real and permanent, acknowledges and

experiences the painful emotions that accompany the loss, experiences life

without the deceased, overcomes impediments to adjustment, and finds a new way

of liv-ing in a world without the loved one. Particularly immediately

fol-lowing the death, the mourner begins to recognize the reality and

permanence of the loss by talking about the deceased and telling and retelling

the story of the illness and death. Societal norms in the United States are

frequently at odds with the normal grieving processes of individuals, where

time excused from work obliga-tions is typically measured in days and mourners

are often ex-pected to get over the loss quickly and get on with life.

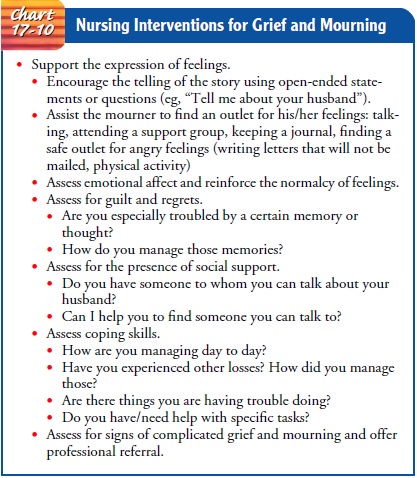

In

reality, the work of grief and mourning takes time, and avoiding grief work following

the death often leads to long-term adjustment difficulties. According to Rando

(2000), mourning for a loss involves the “undoing” of psychosocial ties that

bind the mourner to the deceased, personal adaptation to the loss, and learning

to live in the world without the deceased. Six key processes of mourning allow

the individual to accommodate to the loss in a healthy way: recognition of the

loss; reaction to the separation, experiencing and expressing the pain of the

loss; rec-ollection and re-experiencing the deceased, the relationship, and the

associated feelings; relinquishing old attachments to the de-ceased;

readjustment to adapt to the new world without forget-ting the old; and

reinvestment (Rando, 2000). Similarly, Worden (1991) described four tasks of

mourning: acceptance of the real-ity of the loss, working through the pain of

grief, adjusting to the environment in which the deceased is gone, and

emotional “re-location” of the deceased in order to move on with life.Although

many individuals complete the work of mourning with the informal support of

family and friends, many find that talking with others who have had a similar

experience, such as in formal support groups, normalizes the feelings and

experiences and provides a framework for learning new skills to cope with the

loss and create a new life. Bereavement support groups are often sponsored by

hospitals, hospices, and other community organi-zations. Groups for parents who

have lost a child, children who have lost a parent, widows, widowers, and gay

men and lesbians who have lost a life partner are some examples of specialized

sup-port groups available in many communities. Nursing interven-tions for those

experiencing grief and mourning are identified in Chart 17-10.

Complicated Grief and Mourning

Complicated

grief and mourning are characterized by prolonged feelings of sadness and

feelings of general worthlessness or hope-lessness that persist long after the

death, prolonged symptoms that interfere with activities of daily living

(anorexia, insomnia, fatigue, panic), or self-destructive behaviors such as

alcohol or substance abuse and suicidal ideation or attempts. Complicated grief

and mourning require professional assessment and can be treated with

pharmacologic and psychological interventions.

Related Topics