Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Enterobacteriaceae

Salmonellosis : Clinical Aspects

SALMONELLOSIS : CLINICAL ASPECTS

MANIFESTATIONS

The clinical patterns of salmonellosis can be divided into gastroenteritis, bacteremia with and without focal extraintestinal infection, enteric fever, and the asymptomatic carrier state. Any Salmonella serotype can probably cause any of these clinical manifestations under appropriate conditions, but in practice the S. enterica serotypes are associated pri-marily with gastroenteritis. Typhi and a few related serotypes (Paratyphi) cause enteric fever.

Gastroenteritis

Typically, the episode begins 24 to 48 hours after ingestion, with nausea and vomiting followed by, or concomitant with, abdominal cramps and diarrhea. Diarrhea persists as the predominant symptom for 3 to 4 days and usually resolves spontaneously within 7 days. Fever (39°C) is present in about 50% of the patients. The spectrum of disease ranges from a few loose stools to a severe dysentery-like syndrome.

Bacteremia and Metastatic Infection

The acute gastroenteritis caused by S. enterica can be associated with transient or persistent bacteremia. Frank sepsis is uncommon, except in those with a compromised cell-mediated immune system. Salmonella infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is common and often severe. Bacteremia occurs in 70% of these pa-tients and can cause septic shock and death. Despite adequate antimicrobial coverage, re-lapses are frequent. Patients with lymphoproliferative disease, perhaps owing to T-cell de-fects similar to those in patients with AIDS, are also highly susceptible to disseminated salmonellosis. Metastatic spread by salmonellae is a significant risk when bacteremia occurs. These organisms have a unique ability to colonize sites of preexisting structural abnormality including atherosclerotic plaques, sites of malignancy, and the meninges (especially in infants). Salmonella infection of the bone typically involves the long bones; in particular, sites of trauma, sickle cell injury, and skeletal prosthesis are at risk.

Enteric Fever

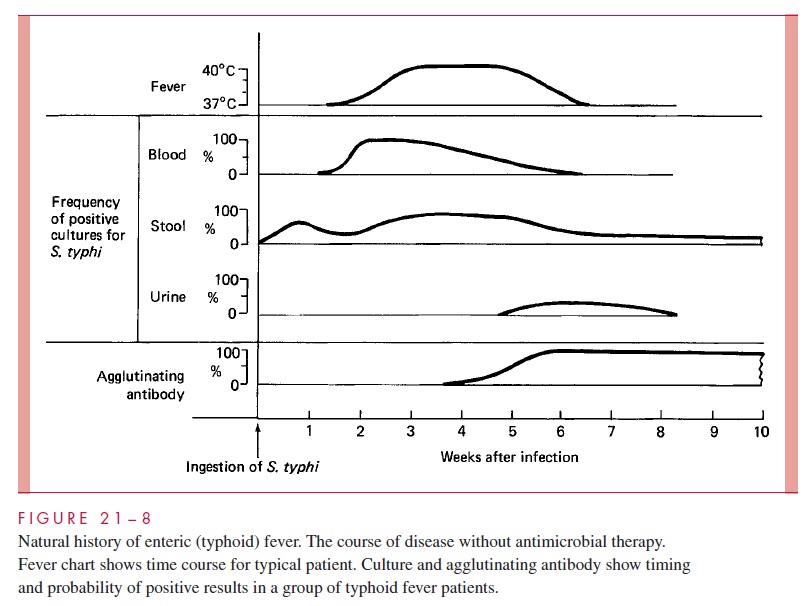

Enteric fever is a multiorgan system Salmonella infection characterized by prolonged fever, sustained bacteremia, and profound involvement of the RES, particularly the mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, and spleen. The manifestations of typhoid (Fig 21 – 8) have been well documented in human volunteer studies conducted during vaccine trials. The mean incubation period is 13 days, and the first sign of disease is fever associated with a headache. The fever rises in a stepwise fashion over the next 72 hours. A relatively slow pulse is characteristic and out of phase with the elevated temperature. In untreated patients, the elevated temperature persists for weeks. A faint rash (rose spots) appears during the first few days on the abdomen and chest. Few in number, these spots are read- ily overlooked, especially in dark-skinned individuals. Many patients are constipated, although perhaps one third of patients have a mild diarrhea. As the untreated disease pro- gresses, an increasing number of patients complain of diarrhea.

Obviously, chronic infection of the bloodstream is a serious disease, and the effects of endotoxin can lead to myocarditis, encephalopathy, or intravascular coagulation. More- over, the persistent bacteremia can lead to infection at other sites. Of particular impor- tance is the biliary tree, with reinfection of the intestinal tract and diarrhea late in the disease. UTI and metastatic lesions in bone, joint, liver, and meninges may also occur. However, the most important complication of typhoid fever is hemorrhage from perfora- tions through the wall of the terminal ileum at the site of necrotic Peyer’s patches or in the proximal colon. These occur in patients whose disease has been progressing for 2 weeks or more.

DIAGNOSIS

Culture of Salmonella from the blood or feces is the primary diagnostic method. Early in the course of enteric fever, blood is far more likely to give a positive culture result than culture from any other site. The media used for stool culture are the same as those used for Shigella. Failure to ferment lactose and the production of hydrogen sulfides from sulfur-containing amino acids are characteristic features used to identify suspect colonies on the selective isolation media. Characteristics of biochemical tests are used to identify the genus, and O serogroup antisera are available in larger laboratories for confirmation. Typhi has a pattern of biochemical reactions which are sufficient to characterize it without refer-ence to its serogroup (D). All isolates should be referred to public health laboratories for confirmation and epidemiologic tracing. Serologic tests are no longer used for diagnosis.

TREATMENT

The primary therapeutic approach to Salmonella gastroenteritis is fluid and electrolyte re-placement and the control of nausea and vomiting. Antibiotic therapy is usually not ap-propriate because it has a tendency to increase the duration and frequency of the carrier state. When used to eradicate the carrier state it meets with erratic success and usually fails in the presence of coexisting biliary tract disease. In patients with underlying risk factors, antimicrobial treatment is used as a prophylactic measure aimed at preventing systemic spread.

Chloramphenicol was the first antibiotic to be used to treat typhoid in 1948, and it re-duced the mortality from 20% to less than 2%. Although resistance has developed, it is still a preferred drug in developing countries because it is inexpensive. Ampicillin and trimethoprim – sulfonamide have been used successfully to treat infections caused by chloramphenicol-resistant strains. Newer cephalosporins (ceftriaxone) and quinolones (ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin) are also effective. With proper antimicrobial therapy, patients feel better in 24 to 48 hours, their temperature returns to normal in 3 to 5 days, and they are generally well in 10 to 14 days.

PREVENTION

Typhoid vaccines have been available since before the turn of the century. An intramuscu-lar killed whole bacterial vaccine was widely used by the military and in travelers but gave poor protection against exposure to large doses of organisms. Recently, a live oral vaccine containing an attenuated Typhi strain has been licensed. Probably as effective as the injectable vaccine, it protects as many as 70% of children in endemic areas. No hu-man vaccine is available for the other Salmonella serotypes. When all is said and done, the provision of clean water supplies and the treatment of carriers will lead to the disap-pearance of typhoid. The importance of carriers and sanitation was emphasized by a 1973 typhoid outbreak among migrant workers in Florida. The source was traced to leakage of sewage into the water supply, failure of chlorination, and a chronic carrier.

Related Topics