Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Enterobacteriaceae

Salmonella Gastroenteritis ( S. enterica)

SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS ( S . enterica )

The typical example of Salmonella “food poisoning” is the community picnic or bazaar, where volunteers prepare poultry, salads, and other potential culture media the food is left out in covered pans. A near physiologic incubation temperature is provided by the still-warm contents and the afternoon sun. This allows the organ- isms to enter logarithmic growth during the softball game. The bacteria usually produce no noticeable change in the food. One to two days after the feast, a sig- nificant portion of the revelers develop abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and di- arrhea lasting for 3 or 4 days. An investigation points to a particular food such as potato salad or turkey dressing, which is found to have a correlation with both at- tack rate and severity of illness.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

S. enterica gastroenteritisis predominantlyadiseaseofindustrializedsocieties and im-proper food handling, which allows the transmission from the animal reservoir to humans. The infecting dose delivered in contaminated food is higher than with Shigella. Ingestion of 1000 or more Salmonella bacilli is required to cause illness, making direct human-to-human transmission difficult. Achlorhydric individuals or those taking antacids can be infected with considerably smaller inocula. Consistently,Salmonella are a leading cause of food-borne intestinal infection under conditions similar to those described in the above capsule.

Poultry products, including eggs infected transovarially, are most often implicated as the vehicle of infection of Salmonella gastroenteritis. Food preparation practices that al-low achievement of an infecting dose by growth of the bacteria in the food prior to inges-tion are most commonly involved. The incidence in the United States is approximately double that of Shigella, with 40,000 to 50,000 reported cases per year. This is believed to reflect only about 1 to 5% of the actual infections. The number of cases varies seasonally, with peak incidence in summer and fall.

The highest rates of infection are in children less than 5 years old, persons aged 20 to 30, and those older than 70. If one household member becomes infected, the probability that another will become infected approaches 60%. Nearly one third of all Salmonella epi-demics occur in nursing homes, hospitals, mental health facilities, and other institutions. A recent increase in the popularity of raw milk has been associated with outbreaks of Salmo-nella (and Campylobacter)infection. Exotic pets suchas turtleshavealsobeen thesourceof infection. Humans can also be the source of disease. Fully 5% of patients recovering from gastroenteritis still shed the organisms 20 weeks later. Chronic carriers who are food handlers are an important reservoir in the epidemiology of food-borne disease.

In recent years, the epidemiology of salmonellosis has changed, and the number of multistate outbreaks has increased, often through the contamination of foodstuffs during large-scale production at a single plant. Efficient interstate and international distribution systems that deliver large amounts of the contaminated food over a wide area facilitate spread. Under these conditions, an attack rate as low as 0.5% can still produce many in-fections, because of the large number of individuals at risk. It is of concern that relatively small numbers of cases sprinkled over a massive area will be missed by local surveillance systems crippled by budgetary cutbacks.

PATHOGENESIS

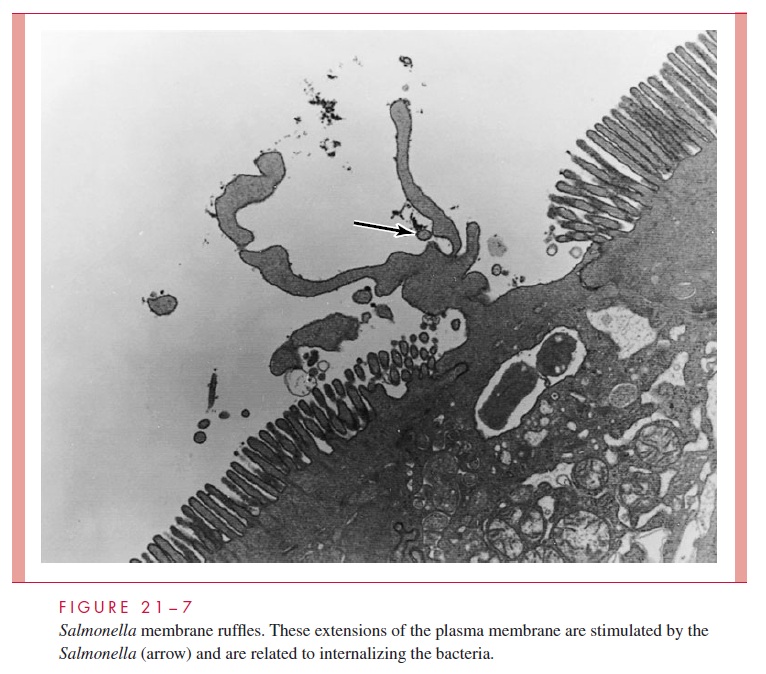

Ingested S.enterica cells that pass the stomach acid and swim through the intestinal mucouslayer eventually reach the enterocytes and M cells of the large and small bowel. Adherence is probably mediated by pili, but on initial contact of bacteria with M cells, the stimulation of membrane “ruffles” dramatically alters the normal architecture within minutes (Fig 21 – 7).

These “ruffles” are specialized mammalian plasma membrane sites of filamentous actin cytoskeletal rearrangement normally induced by physiologic molecules such as growth factors. In the case of Salmonella, they are stimulated by one or more of a family of more than 12 proteins whose genes (invA, invB, spaP, spaQ) are located in at least two PAIs in-serted into the Salmonella genome. The virulence factors coded by the genes in the PAIs are either components of the apparatus of a contact secretion system or the effector pro-teins it injects.

The “ruffles” seem to engulf the organism in an endocytotic vacuole and allow it to transcytose from the apical surface to the basolateral membrane. Once through the cell, the organisms enter the lamina propria, where they induce a profound inflammatory response. When taken up by macrophages, they are able to persist by inducing apoptosis of the phagocyte. Genes for macrophage survival are located in a second PAI. This process con-trasts with Shigella, which escapes the endocytotic vacuole (and double vacuole) and prefers to invade adjacent enterocytes rather than move through to the submucosa.

Although some enterotoxins have been described in Salmonella, their role in diarrhea is unclear. The best estimate is that the invasion and transcytosis of enterocytes together with the associated increased vascular permeability and inflammatory response are enough to account for the diarrhea. The release of prostaglandins and chemotactic factors may trigger inflamma-tion and biochemical changes in enterocytes. Although the process remains localized to the mucosa and submucosa with most S. enterica strains, some invade more deeply, reaching the bloodstream and distant organs. Some serotypes (eg, Choleraesuis) even invade so rapidly that they produce minimal diarrhea and are isolated more frequently from the blood than stool.

IMMUNITY

Evidence that both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses are stimulated by infec- tion withS. entericais ample. How these processes relate to immunity and control of the bacterial infection is largely unknown.

Related Topics