Chapter: Essentials of Anatomy and Physiology: The Respiratory System

Pulmonary Volumes

PULMONARY VOLUMES

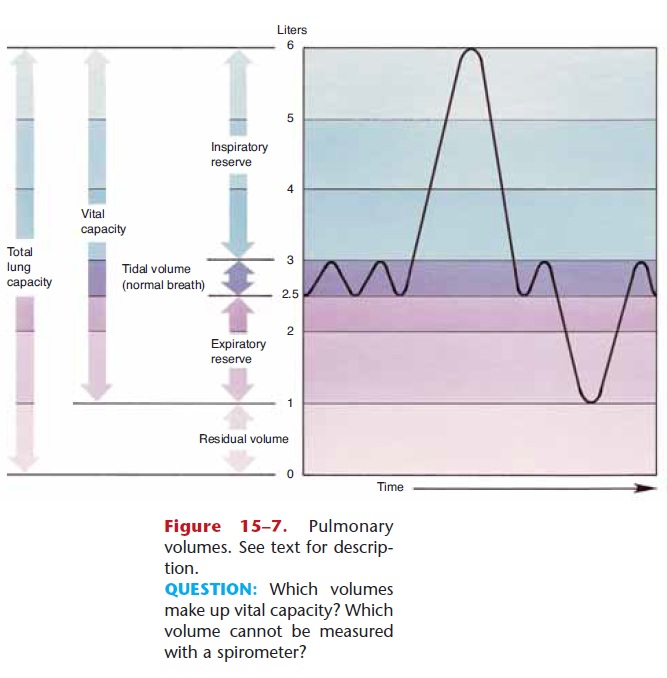

The capacity of the lungs varies with the size and age of the person. Taller people have larger lungs than do shorter people. Also, as we get older our lung capacity diminishes as lungs lose their elasticity and the respi-ratory muscles become less efficient. For the following pulmonary volumes, the values given are those for healthy young adults. These are also shown in Fig. 15–7

1. Tidal volume—the amount of air involved in one normal inhalation and exhalation. The average tidal volume is 500 mL, but many people often have lower tidal volumes because of shallow breathing.

2. Minute respiratory volume (MRV)—the amount of air inhaled and exhaled in 1 minute. MRV is cal-culated by multiplying tidal volume by the number of respirations per minute (average range: 12 to 20 per minute). If tidal volume is 500 mL and the res-piratory rate is 12 breaths per minute, the MRV is 6000 mL, or 6 liters of air per minute, which is average. Shallow breathing usually indicates a smaller than average tidal volume, and would thus require more respirations per minute to obtain the necessary MRV.

3. Inspiratory reserve—the amount of air, beyond tidal volume, that can be taken in with the deepest possible inhalation. Normal inspiratory reserve ranges from 2000 to 3000 mL.

4. Expiratory reserve—the amount of air, beyond tidal volume, that can be expelled with the most forceful exhalation. Normal expiratory reserve ranges from 1000 to 1500 mL.

5. Vital capacity—the sum of tidal volume, inspira-tory reserve, and expiratory reserve. Stated another way, vital capacity is the amount of air involved in the deepest inhalation followed by the most force-ful exhalation. Average range of vital capacity is 3500 to 5000 mL.

6. Residual air—the amount of air that remains in the lungs after the most forceful exhalation; the average range is 1000 to 1500 mL. Residual air is important to ensure that there is some air in the lungs at all times, so that exchange of gases is a con-tinuous process, even between breaths.

Some of the volumes just described can be deter-mined with instruments called spirometers, which measure movement of air. Trained singers and musi-cians who play wind instruments often have vital capacities much larger than would be expected for their height and age, because their respiratory muscles have become more efficient with “practice.” The same is true for athletes who exercise regularly. A person with emphysema, however, must “work” to exhale, and vital capacity and expiratory reserve volume are often much lower than average.

Another kind of pulmonary volume is alveolarventilation, which is the amount of air that actually reaches the alveoli and participates in gas exchange. An average tidal volume is 500 mL, of which 350 to 400 mL is in the alveoli at the end of an inhalation. The remaining 100 to 150 mL of air is anatomic deadspace, the air still within the respiratory passages. Despite the rather grim name, anatomic dead space is normal; everyone has it.

Physiological dead space is not normal, and is the volume of non-functioning alveoli that decrease gas exchange. Causes of increased physiological dead space include bronchitis, pneumonia, tuberculosis, emphy-sema, asthma, pulmonary edema, and a collapsed lung.

The compliance of the thoracic wall and the lungs, that is, their normal expansibility, is necessary for suf-ficient alveolar ventilation. Thoracic compliance may be decreased by fractured ribs, scoliosis, pleurisy, or ascites. Lung compliance will be decreased by any condition that increases physiologic dead space. Nor-mal compliance thus promotes sufficient gas exchange in the alveoli.

Related Topics