Chapter: Psychology: Research Methods

Psychology: Observational Studies

OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES

We’ve now explored some

fundamental tools for psychology research—statistical tools, principles that

govern the definition of variables, and procedures for selecting a sample. But

what can we do with these tools? How do we go about setting up a psy-chological

study? The answer varies considerably, and psychological studies come in many

different forms. In some cases, psychologists observe conditions as they

already exist in the world. Our main example so far—comparing boys and girls in

their level of aggression—has been in this category. This sort of study is

referred to as a quasi-experiment—a

comparison of two or more groups that we did not create; the groups already

existed in the world quite independent of our study.

In other cases, we do correlational studies—we collect

multiple bits of information about each research participant and then examine

the relationships among these bits of information. For example, how important

is it, as we walk through life, to have good self-control—an ability to rein in

our impulses and govern our own thoughts and emo-tions? One study addressed

this broad question by asking people to evaluate various aspects of their own

self-control. Specifically, the participants had to decide how well certain

statements applied to them: “I am good at resisting temptation,” “I am always

on time,” and so on. The investigators also collected other pieces of

information about these same individuals and then looked at the relationships

among these various meas-ures. The data indicated that higher levels of

self-control were associated with better grades in school, fewer symptoms of

mental disorder, less binge eating, and better social relationships (Tangney,

Baumeister, & Boone, 2004). All in all, the study indi-cated the advantages

of self-control and, more broadly, illustrated the sorts of things we can learn

from a correlational study.

Quasi-experiments and

correlational studies are different in important ways (e.g., they usually

require different types of statistical analysis). They are alike, however, because

they both involve data from a natural situation, one that the researcher did

not create. On this basis, we can think of them both as types of observational studies—stud-ies that

observe the world as it is. In a different type of research, though, psychologists

do create (or alter) situations in

order to study them. If, for example, we wanted to ask whether stern warnings

about aggression caused a decrease in bad behaviors, we could give the stern

warning to some children and not to others and then see what happens. In this

case, we’re not studying a previously existing situation; we are adding our own

manipulation—the warnings—to see what this does to the data. Studies of this

sort, involving a change or manipulation, are called experiments.

Ambiguity about Causation

Psychologists often want to study

the effects of factors they cannot control. The inde-pendent variable in our

aggression example—sex—is a good illustration. If we want to learn about the

effect of sex on aggression, therefore, we need to do an observational study,

not an experiment.

Other illustrations are easy to

find. For example, some authors have proposed that birth order is a powerful

influence on personality and that compared to later-born chil-dren, firstborn

children are more likely to identify with their parents and less likely to

rebel. To test this claim, we’ll once again need to study the world as it is

rather than doing an experiment. Plainly, a wide range of issues call for the

use of observational studies; and these studies, when properly designed, are an

important source of evidence for us.

But let’s be clear that observational studies have an important limitation—their ability to tell us about cause and effect. Here’s an example: Suppose a researcher hypothesizes that clinical depression leads to a certain style of thinking in which the person con-stantly mulls over unhappy occasions. To verify this hypothesis, the researcher tests two groups—people who are depressed and people who are not—and has the participants in each group fill out questionnaires designed to assess their thought habits. Let’s suppose further that the researcher finds a difference between the groups—the participants suf-fering from depression are more likely to ruminate on their life difficulties.

How should we think about this

result? It’s possible that depression encourages the habit of rumination; that

would explain why rumination is more likely among people with depression. But,

it’s also possible that cause and effect are the other way around— and so a

tendency toward mulling over life’s problems is actually causing the

depres-sion. That interpretation also fits with the result; but it would have

very different implications for what we might conclude about the roots of

depression as well as how we might try to help people with depression.

In observational studies,

researchers are often uncertain about which variable is the cause and which is

the effect. Worse, sometimes there’s another possibility to consider when

interpreting observational data: Perhaps a third factor, different from the two

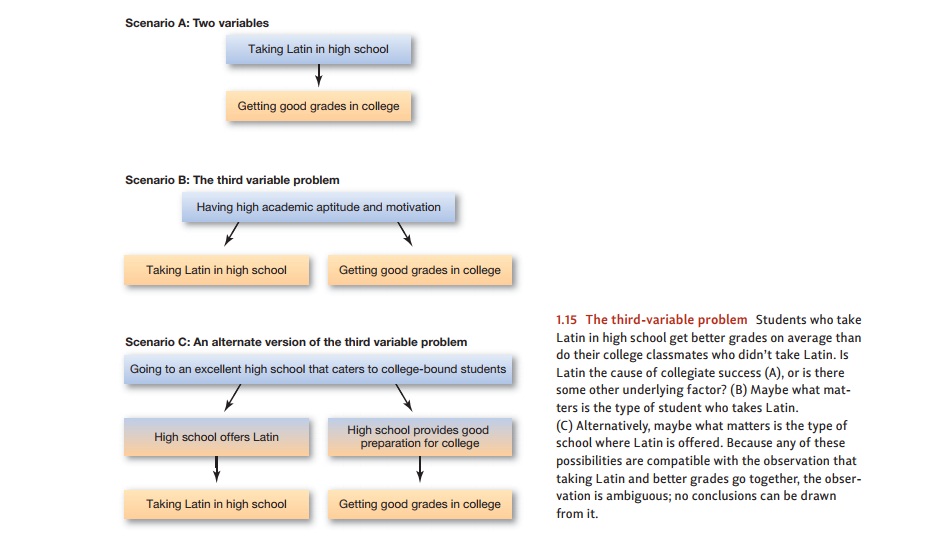

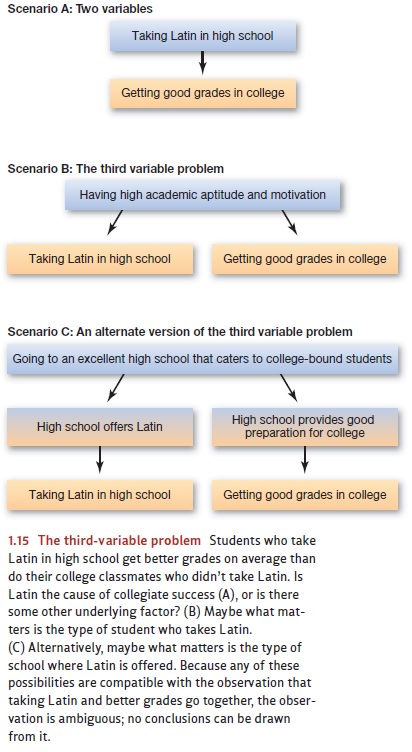

cor-related variables, is causing both. This is the third-variable problem (Figure 1.15). For example, a number of studies have suggested that students who

take Latin in high school often get above-average grades in college, and

there’s an obvious cause-and-effect interpretation for these data: Background

in Latin gives students insight into the roots of many modern words, improving

their vocabulary and thus aiding college performance (Figure 1.15A).

This explanation of the data

certainly seems plausible—but it may not be right, and there are surely other

ways to think about the evidence. For example, what sorts of stu-dents

typically choose to take Latin in high school? In many cases, they’re students

who are academically ambitious, motivated, and able. And, of course, students

with these same traits are likely to do well in college. Thus, these students

have distinctive characteristics—motivation and aptitude—that become the “third

variable,” which leads to taking Latin and to getting better grades in college

(Figure 1.15B). On this basis, taking Latin would be associated with good

college grades, but not because one caused the other. Instead, both effects

might be the products of the same underlying cause. (Figure 1.15C illustrates

yet another possibility—and a different notion of what the third variable might

be in this example.)

These complications—identifying

which factor is the cause and which is the effect, and dealing with the

third-variable problem—often make it difficult to interpret obser-vational

data. Researchers often summarize this difficulty with a simple slogan: Correlation does not imply causation. Of

course, sometimes correlations do reflect causal-ity: Smoking cigarettes is

correlated with, and is a cause of, emphysema, lung cancer, and heart disease.

Being depressed is correlated with, and is actually a cause of, sleep

disruption. But correlations often do not imply causes: The number of ashtrays an

indi-vidual owns is correlated with poor health, but not because owning

ashtrays is haz-ardous. Similarly, there’s a correlation between how many

tomatoes a family eats in a month and how late the children in the family go to

bed—but not because eating toma-toes keeps the kids awake. Instead, tomato

eating and late bedtimes are correlated because they’re both more likely to

occur in the summer.

How can we address these

problems? Sometimes we can disentangle cause and effect simply by collecting

more observational data. For example, in the study of depression and thinking

style, we might be able to determine which of these elements was on the scene

first: Were the people depressed before they started to ruminate? Or were they

ruminating before they became depressed? Here, we’re exploiting the simple

logic that the causes must be in place before the effects. In other cases,

though, it’s just not pos-sible to draw conclusions about cause and effect from

observational data, and so we need to turn to a different type of research—one

that relies on experiments.

Related Topics