Chapter: Psychology: Research Methods

Making Observations: Systematically Collecting Data

Systematically

Collecting Data

Suppose we’ve defined our

question and figured out how to measure our dependent variable. What comes

next? In everyday life, people often try to answer empirical ques-tions by

reflecting on their personal experience. They’ll try to recall cases that seem

rel-evant to the issue being evaluated, and say things like, “What do you mean,

boys are more aggressive? I can think of three girls, just off the top of my

head, who are extremely aggressive.”

This sort of informal “data

collection” may be good enough for some purposes, but it’s unacceptable for

science. For one thing, the “evidence” in such cases is being drawn from

memory—and people’s memories aren’t always accurate. Another problem is that

memories are often selective. We’ll

consider a pattern known as confirmation

bias. This term refers to people’s tendency to recall evidence that

confirms their views more easily than they can recall evidence to the contrary.

So if someone happens to start out with the idea that girls are more

aggres-sive, confirmation bias will lead them to supporting evidence—whether

their initial idea was correct or not.

More broadly, scientists refuse

to draw conclusions from anecdotal

evidence— evidence that involves just one or two cases, has been informally

collected, and is now informally reported. There are many reasons for this

refusal: The anecdotes are often drawn from memory; and, for the reasons just

described, that by itself is a problem. What’s more, anecdotes often report a conclusion drawn from someone’s

observations, but not the observations themselves, and that invites questions

about whether the con-clusion really does follow from the “evidence.” For

example, if someone reports an anec-dote about an aggressive girl, we might

wonder whether the girl’s behavior truly deserved that label—and our

uncertainty obviously weakens the effect of the anecdote.

Perhaps the worst problem with

anecdotal evidence, though, is that the anecdotes may represent exceptions and

not typical cases. This is because, when reporting anec-dotes, people are

likely to overlook the typical cases precisely because they’re familiar and

hence not very interesting. Instead, they’ll recall the cases that stand out

either because they’re extreme or because they don’t follow the usual pattern.

As a result, anec-dotal evidence is often lopsided and misleading.

If we really wanted to compare

boys’ and girls’ aggression, then, how could we avoid all these problems? For a

start, we need to record the data in some neutral and objective way, so there’s

no risk of compromising the quality of our evidence through bias or memory

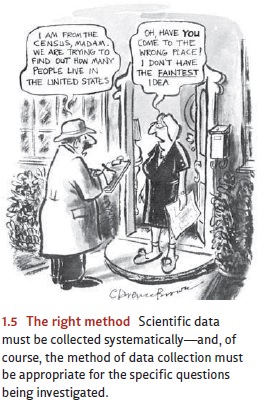

errors. Second, our data collection has to be systematic (Figure 1.5). We might

want to collect observations from all the boys and all the girls at a

particular play-ground; or perhaps, just to keep our project manageable, we

might observe every tenth child who comes to the playground. Notice that these

will be firsthand observations— we’re not relying on questionable anecdotes.

Notice also that our selection of which children to observe (“every tenth

child”) is not guided by our hypothesis. That way, we can be sure we’re not

just collecting cases that happen to be unusual, or cases that sup-port our

claim. This sort of data collection can be cumbersome, but it will give us data

that we can count on in drawing our conclusions.

Related Topics