Chapter: An Introduction to Parallel Programming : Shared-Memory Programming with OpenMP

Producers and Consumers

PRODUCERS

AND CONSUMERS

Let’s take a look at a

parallel problem that isn’t amenable to parallelization using a parallel for or for directive.

1. Queues

Recall that a queue is a list abstract datatype

in which new elements are inserted at the “rear” of the queue and elements are

removed from the “front” of the queue.

A queue can thus be viewed as

an abstraction of a line of customers waiting to pay for their groceries in a

supermarket. The elements of the list are the customers. New customers go to

the end or “rear” of the line, and the next customer to check out is the

customer standing at the “front” of the line.

When a new entry is added to

the rear of a queue, we sometimes say that the entry has been “enqueued,” and

when an entry is removed from the front of a queue, we sometimes say that the

entry has been “dequeued.”

Queues occur frequently in

computer science. For example, if we have a number of processes, each of which

wants to store some data on a hard drive, then a natural way to insure that

only one process writes to the disk at a time is to have the processes form a

queue, that is, the first process that wants to write gets access to the drive

first, the second process gets access to the drive next, and so on.

A queue is also a natural

data structure to use in many multithreaded appli-cations. For example, suppose

we have several “producer” threads and several “consumer” threads. The producer

threads might “produce” requests for data from a server—for example, current

stock prices—while the consumer threads might “consume” the request by finding

or generating the requested data—the current stock prices. The producer threads

could enqueue the requested prices, and the consumer threads could dequeue

them. In this example, the process wouldn’t be completed until the consumer

threads had given the requested data to the producer threads.

2. Message-passing

Another natural application would be

implementing message-passing on a shared-memory system. Each thread could have

a shared message queue, and when one thread wanted to “send a message” to

another thread, it could enqueue the message in the destination thread’s queue.

A thread could receive a message by dequeuing the message at the head of its

message queue.

Let’s implement a relatively simple

message-passing program in which each thread generates random integer “messages”

and random destinations for the mes-sages. After creating the message, the

thread enqueues the message in the appropriate message queue. After sending a

message, a thread checks its queue to see if it has received a message. If it

has, it dequeues the first message in its queue and prints it out. Each thread

alternates between sending and trying to receive messages. We’ll let the user

specify the number of messages each thread should send. When a thread is done

sending messages, it receives messages until all the threads are done, at which

point all the threads quit. Pseudocode for each thread might look something

like this:

for (sent_msgs = 0; sent_msgs < send_max;

sent_msgs++) { Send_msg();

Try_receive();

}

while (!Done())

Try_receive();

3. Sending messages

Note that accessing a message queue to enqueue

a message is probably a critical section. Although we haven’t looked into the

details of the implementation of the message queue, it seems likely that we’ll

want to have a variable that keeps track of the rear of the queue. For example,

if we use a singly linked list with the tail of the list corresponding to the

rear of the queue, then, in order to efficiently enqueue, we would want to

store a pointer to the rear. When we enqueue a new message, we’ll need to check

and update the rear pointer. If two threads try to do this simultaneously, we

may lose a message that has been enqueued by one of the threads. (It might help

to draw a picture!) The results of the two operations will conflict, and hence enqueueing

a message will form a critical section.

Pseudocode for the Send_msg() function might look something like this:

mesg = random();

dest = random() % thread count;

# pragma

omp critical

Enqueue(queue, dest, my_rank, mesg);

Note that this allows a thread to send a

message to itself.

4. Receiving messages

The synchronization issues for receiving a

message are a little different. Only the owner of the queue (that is, the

destination thread) will dequeue from a given message queue. As long as we

dequeue one message at a time, if there are at least two messages in the queue,

a call to Dequeue can’t possibly conflict with any calls to Enqueue, so if we keep track of the size of the queue, we can avoid any

synchronization (for example, critical directives), as long as there are at least two

messages.

Now you may be thinking, “What about the

variable storing the size of the queue?” This would be a problem if we simply

store the size of the queue. However, if we store two variables, enqueued and dequeued, then the number of messages in the queue is

Queue_size = enqueued – dequeued

and the only thread that will update dequeued

is the owner of the queue. Observe that one thread can update enqueued at the

same time that another thread is using it to compute queue_size. To see this,

let’s suppose thread q is computing queue_size. It will either get the old

value of enqueued or the new value. It may therefore compute a queue_size of 0

or 1 when queue_size should actually be 1 or 2, respectively, but in our

program this will only cause a modest delay. Thread q will try again later if

queue_size is 0 when it should be 1, and it will execute the critical section

directive unnecessarily if queue size is 1 when it should be 2.

Thus, we can implement Try_receive as follows:

queue_size = enqueued- dequeued;

if (queue_size == 0) return;

else if (queue_size == 1)

#

pragma omp critical

Dequeue(queue, &src, &mesg);

else

Dequeue(queue, &src, &mesg);

Print_message(src, mesg);

5. Termination detection

We also need to think about implementation of

the Done function. First note that the following “obvious” implementation

will have problems:

queue_size = enqueued-dequeued;

if (queue_size == 0)

return TRUE;

else

return FALSE;

If thread u executes this code, it’s entirely possible that some thread—call

it thread v—will send a message to thread u after u has computed queue_size = 0. Of course, after thread u computes queue_size = 0, it will terminate and the message sent by

thread v will never be received.

However, in our program, after each thread has

completed the for loop, it won’t send any new messages. Thus, if we add a counter done sending, and each thread increments this after completing its for loop, then we can implement Done as follows:

queue size = enqueued - dequeued;

if (queue_size ==

0 && done_sending ==

thread_count)

return TRUE;

else

return FALSE;

6. Startup

When the program begins execution, a single

thread, the master thread, will get command-line arguments and allocate an

array of message queues, one for each thread. This array needs to be shared

among the threads, since any thread can send to any other thread, and hence any

thread can enqueue a message in any of the queues. Given that a message queue

will (at a minimum) store

.. a list of messages,

. a pointer or index to the rear of the queue,

. a pointer or index to the front of the queue,

. a count of messages enqueued, and a count of messages dequeued,

it makes sense to store the queue in a struct,

and in order to reduce the amount of copying when passing arguments, it also

makes sense to make the message queue an array of pointers to structs. Thus,

once the array of queues is allocated by the master thread, we can start the

threads using a parallel directive, and each thread can allocate

storage for its individual queue.

An important point here is that one or more

threads may finish allocating their queues before some other threads. If this

happens, the threads that finish first could start trying to enqueue messages

in a queue that hasn’t been allocated and cause the program to crash. We

therefore need to make sure that none of the threads starts sending messages

until all the queues are allocated. Recall that we’ve seen that sev-eral OpenMP

directives provide implicit barriers when they’re completed, that is, no thread

will proceed past the end of the block until all the threads in the team have

completed the block. In this case, though, we’ll be in the middle of a parallel block, so we can’t rely on an implicit barrier from some other

OpenMP construct—we need an explicit barrier. Fortunately, OpenMP provides one:

# pragma omp barrier

When a thread encounters the barrier, it blocks

until all the threads in the team have reached the barrier. After all the

threads have reached the barrier, all the threads in the team can proceed.

7. The atomic directive

After completing its sends, each thread

increments done sending before proceeding to its final loop of receives. Clearly,

incrementing done sending is a critical section, and we could protect it with a critical directive. However, OpenMP provides a potentially higher

performance directive: the atomic directive:

# pragma omp atomic

Unlike the critical directive, it can only protect critical

sections that consist of a single C assignment statement. Further, the

statement must have one of the following forms:

x <op>= <expression>; x++;

++x;

x-- ;

--x;

Here <op> can be one of the binary operators

+, *, -, /, &, ˆ, | , <<, or

>>.

It’s also important to remember that <expression> must not reference x.

It should be noted that only the load and store

of x are guaranteed to be protected. For example, in the code

pragma omp atomic

x+= y++;

a thread’s update to x will be completed before any other thread can begin updat-ing x. However, the update to y may be unprotected and the results may be

unpredictable.

The idea behind the atomic directive is that many processors provide a special

load-modify-store instruction, and a critical section that only does a

load-modify-store can be protected much more efficiently by using this special

instruc-tion rather than the constructs that are used to protect more general

critical sections.

8. Critical sections and locks

To finish our discussion of the message-passing

program, we need to take a more careful look at OpenMP’s specification of the critical directive. In our earlier examples, our programs had at most one

critical section, and the critical directive forced mutually exclusive access to

the section by all the threads. In this program, however, the use of critical

sections is more complex. If we simply look at the source code, we’ll see three

blocks of code preceded by a critical or an atomic directive:

. done sending++;

. Enqueue(q_p, my_rank, mesg);

. Dequeue(q_p, &src, &mesg);

However, we don’t need to enforce exclusive

access across all three of these blocks of code. We don’t even need to enforce

completely exclusive access within the second and third blocks. For example, it

would be fine for, say, thread 0 to enqueue a message in thread 1’s queue at

the same time that thread 1 is enqueuing a message in thread 2’s queue. But for

the second and third blocks—the blocks protected by critical directives—this is exactly what OpenMP does. From OpenMP’s point

of view our program has two distinct critical sections: the critical section

protected by the atomic directive, done

sending++, and the “composite”

critical section in which we enqueue and dequeue messages.

Since enforcing mutual exclusion among threads

serializes execution, this default behavior of OpenMP—treating all critical

blocks as part of one composite critical section—can be highly detrimental to

our program’s performance. OpenMP does provide the option of adding a name to a critical directive:

# pragma omp critical(name)

When we do this, two blocks protected with critical directives with different names can be executed simultaneously. However, the names are set during

compi-lation, and we want a different critical section for each thread’s queue.

Therefore, we need to set the names at run-time, and in our setting, when we

want to allow simul-taneous access to the same block of code by threads

accessing different queues, the named critical directive isn’t sufficient.

The alternative is to use locks.4 A lock consists of a data

structure and functions that allow the programmer to explicitly enforce mutual

exclusion in a critical section. The use of a lock can be roughly described by

the following pseudocode:

/* Executed

by one thread */

Initialize the lock data structure;

. . .

/* Executed

by multiple threads */

Attempt to lock or set the lock data structure;

Critical section;

Unlock or unset the lock data structure;

. . .

/* Executed

by one thread */

Destroy the lock data structure;

The lock data structure is shared among the

threads that will execute the critical section. One of the threads (e.g., the

master thread) will initialize the lock, and when all the threads are done

using the lock, one of the threads should destroy it.

Before a thread enters the critical section, it

attempts to set or lock the lock data structure by calling the lock function. If

no other thread is executing code in the critical section, it obtains the lock and proceeds into the critical

section past the call to the lock function. When the thread finishes the code

in the critical section, it calls an unlock function, which relinquishes or unsets the lock and allows another thread to obtain the lock.

While a thread owns the lock, no other thread

can enter the critical section. If another thread attempts to enter the

critical section, it will block when it calls the lock function. If multiple threads are blocked

in a call to the lock function, then when the thread in the critical section

relinquishes the lock, one of the blocked threads returns from the call to the

lock, and the others remain blocked.

OpenMP has two types of locks: simple locks and nested locks. A simple lock can only be set once before it is unset,

while a nested lock can be set multiple times by the same thread before it is unset.

The type of an OpenMP simple lock is omp lock

t, and the simple lock functions that we’ll be

using are

void omp_init_lock(omp_lock_t* lock p /* out */);

void omp_set_lock(omp_lock_t* lock_p /* in/out

*/);

void omp_unset_lock(omp_lock_t* lock_p /* in/out */);

void omp_destroy_lock(omp_lock_t* lock_p /* in/out */);

The type and the functions are specified in omp.h. The first function initializes the lock so that it’s unlocked,

that is, no thread owns the lock. The second function attempts to set the lock.

If it succeeds, the calling thread proceeds; if it fails, the calling thread

blocks until the lock becomes available. The third function unsets the lock so

another thread can obtain it. The fourth function makes the lock

uninitial-ized. We’ll only use simple locks. For information about nested

locks, see [8, 10], or [42].

9. Using locks in the message-passing

program

In our earlier discussion of the limitations of

the critical directive, we saw that in the message-passing program, we wanted

to insure mutual exclusion in each individ-ual message queue, not in a

particular block of source code. Locks allow us to do this. If we include a

data member with type omp lock t in our queue struct, we can simply call omp set lock each time we want to insure exclusive access to a message queue.

So the code

pragma

omp critical

/* q p =

msg_queues[dest] */

Enqueue(q p, my_rank, mesg);

can be replaced with

/ q

p = msg_queues[dest] /

omp_set_lock(&q p >lock);

Enqueue(q_p, my_rank, mesg);

omp_unset_lock(&q_p >lock);

Similarly, the code

# pragma

omp critical

/* q_p =

msg_queues[my_rank] */

Dequeue(q_p, &src, &mesg);

can be replaced with

/* q_p

= msg_queues[my_rank] */

omp_set_lock(&q_p->lock);

Dequeue(q_p, &src, &mesg);

omp_unset_lock(&q_p

->lock);

Now when a thread tries to send or receive a

message, it can only be blocked by a thread attempting to access the same

message queue, since different message queues have different locks. In our

original implementation, only one thread could send at a time, regardless of

the destination.

Note that it would also be possible to put the

calls to the lock functions in the queue functions Enqueue and Dequeue. However, in order to preserve the

perfor-mance of Dequeue, we would also need to move the code that

determines the size of the queue (enqueued – dequeued) to Dequeue. Without it, the Dequeue function will lock the queue every time it is called by Try receive. In the interest of preserving the structure of the code we’ve

already written, we’ll leave the calls to omp_set_lock and omp_unset_lock in the Send and Try_receive functions.

Since we’re now including the lock associated

with a queue in the queue struct, we can add initialization of the lock to the

function that initializes an empty queue.

Destruction of the lock can be done by the

thread that owns the queue before it frees the queue.

10. critical directives, atomic directives, or

locks?

Now that we have three mechanisms for enforcing

mutual exclusion in a critical section, it’s natural to wonder when one method

is preferable to another. In gen-eral, the atomic directive has the potential to be the fastest

method of obtaining mutual exclusion. Thus, if your critical section consists

of an assignment statement having the required form, it will probably perform

at least as well with the atomic directive as the other methods. However, the

OpenMP specification [42] allows the atomic directive to enforce mutual exclusion across all

atomic directives in the program—this is the way the unnamed critical directive behaves. If this might be a problem—for example, you

have multiple different critical sections protected by atomic directives—you should use named

critical directives or locks. For

exam-ple, suppose we have a program in which it’s possible that one thread will

execute the code on the left while another executes the code on the right.

# pragma

omp atomic

# pragma

omp atomic

x++; y++;

Even if x and y are unrelated memory locations, it’s possible

that if one thread is executing x++, then no thread can simultaneously execute y++. It’s important to note that the standard doesn’t require this

behavior. If two statements are protected by atomic directives and the two statements modify

different variables, then there are implementations that treat the two

statements as different critical sections. See Exercise 5.10. On the other

hand, different statements that modify the same vari-able will be treated as if they belong to the same

critical section, regardless of the implementation.

We’ve already seen some limitations to the use

of critical directives. However, both named and unnamed critical directives are very easy to use. Furthermore, in the

implementations of OpenMP that we’ve used there doesn’t seem to be a very large

difference between the performance of critical sections protected by a critical

directive, and critical sections protected by locks, so if you can’t

use an atomic directive, but you can use a critical directive, you probably should. Thus, the use

of locks should probably be reserved for situations in which mutual exclusion

is needed for a data structure rather than a block of code.

11. Some caveats

You should exercise caution

when you’re using the mutual exclusion techniques we’ve discussed. They can

definitely cause serious programming problems. Here are a few things to be

aware of:

1. You shouldn’t mix the different types of mutual exclusion for a

single critical section. For example, suppose a program contains the following

two segments.

# pragma omp atomic

x +=

f(y);

# pragma omp critical

x =

g(x);

The update to x on the right doesn’t have the form required by

the atomic direc-tive, so the

programmer used a critical directive. However, the critical directive won’t exclude the action executed by

the atomic block, and it’s pos-sible

that the results will be incorrect. The programmer needs to either rewrite the

function g so that its use can have the form required by

the atomic directive, or she needs to

protect both blocks with a critical directive.

2. There is no guarantee of fairness in mutual exclusion

constructs. This means that it’s possible that a thread can be blocked forever

in waiting for access to a critical section. For example, in the code

while(1)

{

. .

pragma omp critical x = g(my_rank);

. .

}

it’s possible that, for example, thread 1 can

block forever waiting to execute x = g(my_rank), while the other threads repeatedly execute

the assignment. Of course, this wouldn’t be an issue if the loop

terminated. Also note that many implementations give threads access to the

critical section in the order in which they reach it, and for these

implementations, this won’t be an issue.

It can be dangerous to “nest” mutual exclusion

constructs. As an example, suppose a program contains the following two

segments.

pragma omp critical y = f(x);

. . .

double

f(double x) {

pragma omp critical

z =

g(x); /

z is shared /

. .

}

This is guaranteed to deadlock. When a thread attempts to enter the second

crit-ical section, it will block forever. If thread u is executing code in the first critical block, no thread can

execute code in the second block. In particular, thread u can’t execute this code. However, if thread u is blocked waiting to enter the second

critical block, then it will never leave the first, and it will stay blocked

forever.

In this example, we can solve the problem by

using named critical sections. That is, we could rewrite the code as

pragma omp critical(one) y = f(x);

. . .

double

f(double x) {

# pragma omp critical(two)

z =

g(x); /*

z is global */

. . .

}

However, it’s not difficult

to come up with examples when naming won’t help. For example, if a program has

two named critical sections—say one and two— and threads can attempt to enter the critical

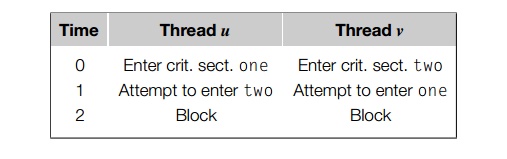

sections in different orders, then deadlock can occur. For example, suppose

thread u enters one at the same time that thread v enters two and u then attempts to enter two while v attempts to enter one:

Then both u and v will block forever waiting

to enter the critical sections. So it’s not enough to just use different names

for the critical sections—the program-mer must insure that different critical

sections are always entered in the same order.

Related Topics