Chapter: Compilers : Principles, Techniques, & Tools : Instruction-Level Parallelism

Processor Architectures

Processor Architectures

1

Instruction Pipelines and Branch Delays

2

Pipelined Execution

3

Multiple Instruction Issue

When we think of instruction-level parallelism, we usually imagine

a processor issuing several operations in a single clock cycle. In fact, it is

possible for a machine to issue just one operation per clock1 and yet

achieve instruction-level parallelism using the concept of pipelining.

In the following, we shall first explain pipelining then discuss

multiple-instruction issue.

1. Instruction Pipelines and Branch Delays

Practically every processor, be it a high-performance

supercomputer or a stan-dard machine, uses an instruction pipeline. With

an instruction pipeline, a new instruction can be fetched every clock while

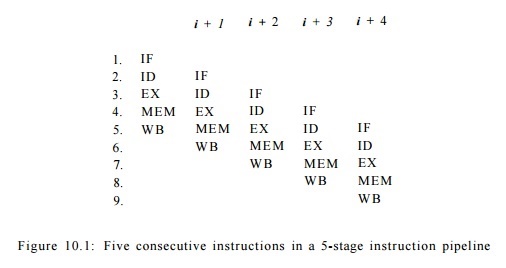

preceding instructions are still going through the pipeline. Shown in Fig. 10.1

is a simple 5-stage instruction pipeline: it first fetches the instruction

(IF), decodes it (ID), executes the op-eration (EX), accesses the memory (MEM),

and writes back the result (WB). The figure shows how instructions i, i +

1, i + 2, i + 3, and i + 4 can execute at the same time.

Each row corresponds to a clock tick, and each column in the figure specifies

the stage each instruction occupies at each clock tick.

If the result from an instruction is available by

the time the succeeding in-struction needs the data, the processor can issue an

instruction every clock. Branch instructions are especially problematic because

until they are fetched, decoded and executed, the processor does not know which

instruction will ex-ecute next. Many processors speculatively fetch and decode

the immediately succeeding instructions in case a branch is not taken. When a

branch is found to be taken, the instruction pipeline is emptied and the branch

target is fetched.

Thus, taken branches introduce a delay in the fetch of the branch

target and introduce "hiccups" in the instruction pipeline. Advanced

processors use hard-ware to predict the outcomes of branches based on their

execution history and to prefetch from the predicted target locations. Branch

delays are nonetheless observed if branches are mispredicted.

2.

Pipelined Execution

Some instructions take several clocks to execute.

One common example is the memory-load operation. Even when a memory access hits

in the cache, it usu-ally takes several clocks for the cache to return the

data. We say that the execution of an instruction is pipelined if

succeeding instructions not dependent on the result are allowed to proceed.

Thus, even if a processor can issue only one operation per clock, several

operations might be in their execution stages at the same time. If the deepest

execution pipeline has n stages, potentially n operations can be "in flight" at the same time. Note that not all instructions are fully

pipelined. While floating-point adds and multiplies often are fully pipelined,

floating-point divides, being more complex and less frequently executed, often

are not.

Most general-purpose processors dynamically detect

dependences between consecutive instructions and automatically stall the

execution of instructions if their operands are not available. Some processors,

especially those embedded in hand-held devices, leave the dependence checking

to the software in order to keep the hardware simple and power consumption low.

In this case, the compiler is responsible for inserting "no-op"

instructions in the code if necessary to assure that the results are available

when needed.

3. Multiple Instruction Issue

By issuing several operations per clock, processors can keep even

more opera-tions in flight. The largest number of operations that can be

executed simul-taneously can be computed by multiplying the instruction issue

width by the average number of stages in the execution pipeline.

Like pipelining, parallelism on multiple-issue machines can be

managed ei-ther by software or hardware. Machines that rely on software to

manage their parallelism are known as VLIW (Very-Long-Instruction-Word)

machines, while those that manage their parallelism with hardware are known as superscalar

machines. VLIW machines, as their name implies, have wider than normal

instruction words that encode the operations to be issued in a single clock.

The compiler decides which operations are to be issued in parallel and encodes

the information in the machine code explicitly. Superscalar machines, on the

other hand, have a regular instruction set with an ordinary

sequential-execution semantics. Superscalar machines automatically detect

dependences among in-structions and issue them as their operands become

available. Some processors include both VLIW and superscalar functionality.

Simple hardware schedulers execute instructions in the order in

which they are fetched. If a scheduler comes across a dependent instruction, it

and all instructions that follow must wait until the dependences are resolved

(i.e., the needed results are available). Such machines obviously can benefit

from having a static scheduler that places independent operations next to each

other in the order of execution.

More sophisticated schedulers can execute instructions "out

of order." Op-erations are independently stalled and not allowed to

execute until all the values they depend on have been produced. Even these

schedulers benefit from static scheduling, because hardware schedulers have

only a limited space in which to buffer operations that must be stalled. Static

scheduling can place independent operations close together to allow better

hardware utilization. More impor-tantly, regardless how sophisticated a dynamic

scheduler is, it cannot execute instructions it has not fetched. When the

processor has to take an unexpected branch, it can only find parallelism among

the newly fetched instructions. The compiler can enhance the performance of the

dynamic scheduler by ensuring that these newly fetched instructions can execute

in parallel.

Related Topics