Chapter: Compilers : Principles, Techniques, & Tools : Instruction-Level Parallelism

Code-Scheduling Constraints

Code-Scheduling Constraints

1 Data

Dependence

2 Finding

Dependences Among Memory Accesses

3 Tradeoff

Between Register Usage and Parallelism

4 Phase

Ordering Between Register Allocation and Code Scheduling

5 Control

Dependence

6 Speculative

Execution Support

7 A Basic

Machine Model

8 Exercises for

Section 10.2

Code scheduling is a form of program optimization

that applies to the machine code that is produced by the code generator. Code

scheduling is subject to three kinds of constraints:

2. Data-dependence constraints. The operations in

the optimized program must produce the same results as the corresponding ones

in the original program.

3. Resource constraints. The schedule must not

oversubscribe the resources on the machine.

These scheduling constraints guarantee that the optimized program

pro-duces the same results as the original. However, because code scheduling

changes the order in which the operations execute, the state of the memory at

any one point may not match any of the memory states in a sequential

ex-ecution. This situation is a problem if a program's execution is interrupted

by, for example, a thrown exception or a user-inserted breakpoint. Optimized

programs are therefore harder to debug. Note that this problem is not specific

to code scheduling but applies to all other optimizations, including

partial-redundancy elimination (Section 9.5) and register allocation (Section

8.8).

1.

Data Dependence

It is easy to see that if we change the execution order of two

operations that do not touch any of the same variables, we cannot possibly

affect their results. In fact, even if these two operations read the same

variable, we can still permute their execution. Only if an operation writes to

a variable read or written by another can changing their execution order alter

their results. Such pairs of operations are said to share a data dependence,

and their relative execution order must be preserved. There are three flavors

of data dependence:

1.

True

dependence: read after write. If

a write is followed by a read of the same location, the read depends on

the value written; such a dependence is known as a true dependence.

2.

Antidependence:

write after read. If a read is

followed by a write to the same location, we say that there is an

antidependence from the read to the write. The write does not depend on the

read per se, but if the write happens before the read, then the read operation

will pick up the wrong value. Antidependence is a byproduct of imperative

programming, where the same memory locations are used to store different

values. It is not a "true" dependence and potentially can be

eliminated by storing the values in different locations.

3.

Output

dependence: write after write.

Two writes to the same location share an output dependence. If the

dependence is violated, the value of the memory location written will have the

wrong value after both operations are performed.

Antidependence and output dependences are referred to as storage-related

de-pendences. These are not "true" dependences and can be

eliminated by using different locations to store different values. Note that

data dependences apply to both memory accesses and register accesses.

2. Finding Dependences Among Memory Accesses

To check if two

memory accesses share a data dependence, we only need to tell if they can refer

to the same location; we do not need to know which location is being accessed.

For example, we can tell that the two accesses *p and O p ) + 4 cannot refer to

the same location, even though we may not know what p points to. Data

dependence is generally undecidable at compile time. The compiler must assume

that operations may refer to the same location unless it can prove otherwise.

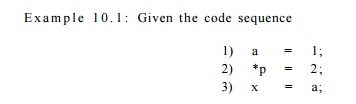

unless the compiler knows that p cannot possibly point to

a, it must conclude that the three operations need to execute serially. There

is an output depen-dence flowing from statement (1) to statement (2), and there

are two true dependences flowing from statements (1) and (2) to statement (3).

•

Data-dependence analysis is highly sensitive to the programming

language used in the program. For type-unsafe languages like C and C + + ,

where a pointer can be cast to point to any kind of object, sophisticated

analysis is necessary to prove independence between any pair of pointer-based

memory ac-cesses. Even local or global scalar variables can be accessed

indirectly unless we can prove that their addresses have not been stored

anywhere by any instruc-tion in the program. In type-safe languages like Java,

objects of different types are necessarily distinct from each other. Similarly,

local primitive variables on the stack cannot be aliased with accesses through

other names.

A correct discovery of data dependences requires a number of

different forms of analysis. We shall focus on the major questions that must be

resolved if the compiler is to detect all the dependences that exist in a

program, and how to use this information in code scheduling. Later chapters

show how these analyses are performed.

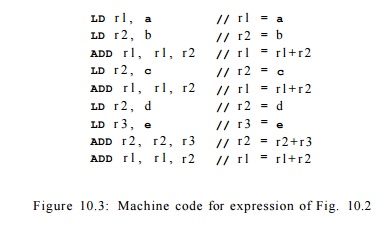

Array Data - Dependence Analysis

Array data dependence

is the problem of disambiguating between the values of indexes in array-element

accesses. For example, the loop

copies odd elements in the array A to the even elements

just preceding them. Because all the read and written locations in the loop are

distinct from each other, there are no dependences between the accesses, and

all the iterations in the loop can execute in parallel. Array data-dependence

analysis, often referred to simply as data-dependence analysis, is very

important for the optimization of numerical applications. This topic will be

discussed in detail in Section 11.6.

Pointer - Alias Analysis

We say that two pointers are aliased if they can refer to

the same object. Pointer-alias analysis is difficult because there are many

potentially aliased pointers in a program, and they can each point to an

unbounded number of dynamic objects over time. To get any precision,

pointer-alias analysis must be applied across all the functions in a program.

This topic is discussed starting in Section 12.4.

Interprocedural Analysis

For languages that pass parameters by reference, interprocedural

analysis is needed to determine if the same variable is passed as two or more

different arguments. Such aliases can create dependences between seemingly

distinct parameters. Similarly, global variables can be used as parameters and

thus create dependences between parameter accesses and global variable

accesses. Interprocedural analysis, discussed in Chapter 12, is necessary to

determine these aliases.

3. Tradeoff Between Register Usage and Parallelism

In this chapter we shall assume that the machine-independent

intermediate rep-resentation of the source program uses an unbounded number of pseudoregisters

to represent variables that can be allocated to registers. These variables

include scalar variables in the source program that cannot be referred to by

any other names, as well as temporary variables that are generated by the

compiler to hold the partial results in expressions. Unlike memory locations,

registers are uniquely named. Thus precise data-dependence constraints can be

generated for register accesses easily.

The unbounded number

of pseudoregisters used in the intermediate repre-sentation must eventually be

mapped to the small number of physical registers available on the target

machine. Mapping several pseudoregisters to the same physical register has the

unfortunate side effect of creating artificial storage dependences that

constrain instruction-level parallelism. Conversely, executing instructions in

parallel creates the need for more storage to hold the values being computed

simultaneously. Thus, the goal of minimizing the number of registers used

conflicts directly with the goal of maximizing instruction-level parallelism.

Examples 10.2 and 10.3 below illustrate this classic trade-off between storage

and parallelism.

Hardware Register Renaming

Instruction-level

parallelism was first used in computer architectures as a means to speed up

ordinary sequential machine code. Compilers at the time were not aware of the

instruction-level parallelism in the machine and were designed to optimize the

use of registers. They deliberately reordered instructions to minimize the

number of registers used, and as a result, also minimized the amount of

parallelism available. Example 10.3

illustrates how minimizing register usage in the computation of expression

trees also limits its parallelism.

There was so little

parallelism left in the sequential code that computer architects invented

the concept of

hardware register renaming to undo the effects of register optimization

in compilers. Hardware register renaming

dynamically changes the assignment of registers as the program runs. It interprets the machine code, stores values

intended for the same register in different internal registers, and updates all

their uses to refer to the right registers accordingly.

Since the artificial

register-dependence constraints were introduced by the compiler in the first

place, they can be eliminated by using a register-allocation algorithm that is

cognizant of instruction-level paral-lelism. Hardware register renaming is

still useful in the case when a ma-chine's instruction set can only refer to a

small number of registers. This capability allows an implementation of the

architecture to map the small number of architectural registers in the code to

a much larger number of internal registers dynamically.

Example 10.2 : The code below copies the values of variables

in locations a and c to variables in locations b and d, respectively, using

pseudoregisters tl and t2.

LD t l , a

ST b , t l

LD t2, c

ST d, t2

/ / t l = a

/ / b = t l

/ / t2 = c

/ / d = t2

If all the memory

locations accessed are known to be distinct from each other, then the copies

can proceed in parallel. However, if tl and t2 are assigned the same register

so as to minimize the number of registers used, the copies are necessarily

serialized. •

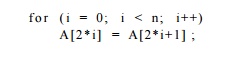

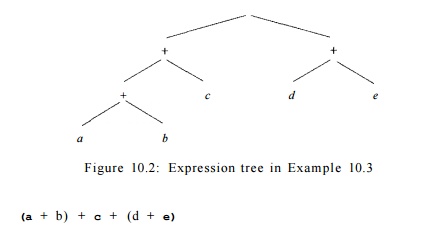

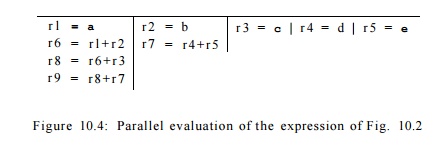

Example 10.3 :

Traditional register-allocation techniques aim to minimize the number of

registers used when performing a computation. Consider the expression

shown as a syntax

tree in Fig. 10.2. It is possible to perform this computation using three

registers, as illustrated by the machine code in Fig. 10.3.

The reuse of registers, however, serializes the computation. The

only oper-ations allowed to execute in parallel are the loads of the values in

locations a and b, and the loads of the values in locations d

and e. It thus takes a total of 7 steps to complete the

computation in parallel.

Had we used different

registers for every partial sum, the expression could be evaluated in 4 steps,

which is the height of the expression tree in Fig. 10.2. The parallel

computation is suggested by Fig. 10.4.

4. Phase Ordering Between Register Allocation and Code Scheduling

If registers are allocated before scheduling, the resulting code

tends to have many storage dependences that limit code scheduling. On the other

hand, if code is scheduled before register allocation, the schedule created may

require so many registers that register

spilling (storing the contents

of a register in a memory location, so the register can be used for some

other purpose) may negate the advantages of instruction-level parallelism.

Should a compiler allo-cate registers first before it schedules the code? Or

should it be the other way round? Or, do we need to address these two problems

at the same time?

To answer the questions above, we must consider the

characteristics of the programs being compiled. Many nonnumeric applications do

not have that much available parallelism. It suffices to dedicate a small

number of registers for holding temporary results in expressions. We can first

apply a coloring algorithm, as in Section 8.8.4, to allocate registers for all the

nontemporary variables, then schedule the code, and finally assign registers to

the temporary variables.

This approach does

not work for numeric applications where there are many more large expressions.

We can use a hierarchical approach where code is op-timized inside out,

starting with the innermost loops. Instructions are first scheduled assuming

that every pseudoregister will be allocated its own physical register. Register

allocation is applied after scheduling and spill code is added where necessary,

and the code is then rescheduled. This process is repeated for the code in the

outer loops. When several inner loops are considered together in a common outer

loop, the same variable may have been assigned different registers. We can

change the register assignment to avoid having to copy the values from one

register to another. In Section 10.5, we shall discuss the in-teraction between

register allocation and scheduling further in the context of a specific

scheduling algorithm.

5. Control

Dependence

Scheduling operations within a basic block is relatively easy

because all the instructions are guaranteed to execute once control flow

reaches the beginning of the block. Instructions in a basic block can be

reordered arbitrarily, as long as all the data dependences are satisfied.

Unfortunately, basic blocks, especially in nonnumeric programs, are typically

very small; on average, there are only about five instructions in a basic

block. In addition, operations in the same block are often highly related and thus

have little parallelism. Exploiting parallelism across basic blocks is

therefore crucial.

An optimized program

must execute all the operations in the original pro-gram. It can execute more

instructions than the original, as long as the extra instructions do not change

what the program does. Why would executing extra instructions speed up a

program's execution? If we know that an instruction is likely to be executed,

and an idle resource is available to perform the opera-tion "for

free," we can execute the instruction speculatively. The program

runs faster when the speculation turns out to be correct.

An instruction

n is said to be control-dependent on instruction

i2 if the outcome of i2 determines whether h is to be executed. The

notion of control dependence corresponds to the concept of nesting levels in

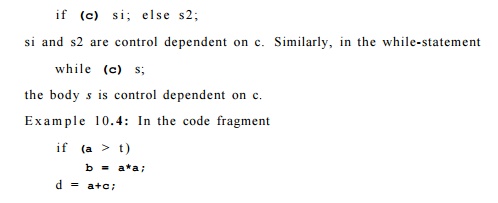

block-structured programs. Specifically, in the if-else statement

the statements b = a*a and d = a+c have no data dependence with any other part of

the fragment. The statement b = a*a depends on the comparison a > t. The

statement d = a+c, however, does not depend on the comparison and

can be executed any time. Assuming that the multiplication a * a does

not cause any side effects, it can be performed speculatively, as long as b

is written only after a is found to be greater than t. •

6. Speculative Execution Support

Memory loads are one type of instruction that can benefit greatly

from specula-tive execution. Memory loads are quite common, of course. They

have relatively long execution latencies, addresses used in the loads are

commonly available in advance, and the result can be stored in a new temporary

variable without destroying the value of any other variable. Unfortunately,

memory loads can raise exceptions if their addresses are illegal, so

speculatively accessing illegal addresses may cause a correct program to halt

unexpectedly. Besides, mispre-dicted memory loads can cause extra cache misses

and page faults, which are extremely costly.

Example 10.5

: In the fragment

if (p

!= n u l l )

q = *P;

dereferencing p speculatively will cause this correct

program to halt in error if p is null .

Many high-performance

processors provide special features to support spec-ulative memory accesses. We

mention the most important ones next.

Prefetching

The prefetch instruction was invented to bring data from

memory to the cache before it is used. A prefetch instruction indicates

to the processor that the program is likely to use a particular memory word in

the near future. If the location specified is invalid or if accessing it causes

a page fault, the processor can simply ignore the operation. Otherwise, the

processor will bring the data from memory to the cache if it is not already

there.

Poison Bits

Another architectural feature called poison bits was

invented to allow specu-lative load of data from memory into the register file.

Each register on the machine is augmented with a poison bit. If illegal

memory is accessed or the accessed page is not in memory, the processor does

not raise the exception im-mediately but instead just sets the poison bit of

the destination register. An exception is raised only if the contents of the

register with a marked poison bit are used.

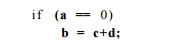

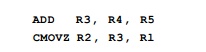

Predicated Execution

Because branches are expensive, and mispredicted branches are even

more so (see Section 10.1), predicated instructions were invented to

reduce the number of branches in a program. A predicated instruction is like a

normal instruction but has an extra predicate operand to guard its execution;

the instruction is executed only if the predicate is found to be true.

As an example, a

conditional move instruction CMOVZ

R2,R3,R1 has the semantics

that the contents of register R3 are moved to register R2 only if register Rl is zero. Code such as

can be implemented

with two machine instructions, assuming that a, b, c, and d are

allocated to registers Rl,

R2, R4, R5, respectively, as follows:

This conversion replaces a series of instructions sharing a

control dependence with instructions sharing only data dependences. These

instructions can then be combined with adjacent basic blocks to create a larger

basic block. More importantly, with this code, the processor does not have a

chance to mispredict, thus guaranteeing that the instruction pipeline will run

smoothly.

Predicated execution

does come with a cost. Predicated instructions are fetched and decoded, even

though they may not be executed in the end. Static schedulers must reserve all

the resources needed for their execution and ensure

Dynamically Scheduled

Machines

The instruction set of a statically scheduled machine explicitly

defines what can execute in parallel. However, recall from Section 10.1.2 that

some ma-chine architectures allow the decision to be made at run time about

what can be executed in parallel. With dynamic scheduling, the same machine

code can be run on different members of the same family (machines that

implement the same instruction set) that have varying amounts of

parallel-execution support. In fact, machine-code compatibility is one of the

major advantages of dynamically scheduled machines.

Static schedulers, implemented in the compiler by software, can

help dynamic schedulers (implemented in the machine's hardware) better utilize

machine resources. To build a static scheduler for a dynamically sched-uled

machine, we can use almost the same scheduling algorithm as for statically

scheduled machines except that no - op instructions left in the schedule need

not be generated explicitly. The matter is discussed further in Section 10.4.7.

that all the potential data dependences are satisfied. Predicated

execution should not be used aggressively unless the machine has many more

resources than can possibly be used otherwise.

7. A Basic Machine Model

Many machines can be represented using the following simple model.

A machine M = {R,T), consists of:

1.

A set of

operation types T, such as loads, stores, arithmetic operations, and so on.

2.

A vector R =

[n, r2,... ] representing hardware resources, where r« is the number of

units available of the ith kind of resource. Examples of typical

resource types include: memory access units, ALU's, and floating-point

functional units.

Each operation has a set of input operands, a set of output

operands, and a resource requirement. Associated with each input operand is an

input latency indicating when the input value must be available (relative to

the start of the operation). Typical input operands have zero latency, meaning

that the values are needed immediately, at the clock when the operation is

issued. Similarly, associated with each output operand is an output latency,

which indicates when the result is available, relative to the start of the

operation.

Resource usage for each machine operation type t is modeled

by a two-dimensional resource-reservation table, RTt. The width of the table is the number of kinds of

resources in the machine, and its length is the duration over which resources

are used by the operation. Entry RTt[i,j] is the number of units of the j t h resource used

by an operation of type t, i clocks after it is issued. For notational

simplicity, we assume RTt[i,j] = 0 if i refers to a nonex-istent entry in the table (i.e., i

is greater than the number of clocks it takes to execute the operation). Of

course, for any t, i, and j, RTt[i,j] must be less than or equal to R[j], the

number of resources of type j that the machine has.

Typical machine

operations occupy only one unit of resource at the time an operation is issued.

Some operations may use more than one functional unit. For example, a

multiply-and-add operation may use a multiplier in the first clock and an adder

in the second. Some operations, such as a divide, may need to occupy a resource

for several clocks. Fully pipelined operations are those that can be

issued every clock, even though their results are not available until some

number of clocks later. We need not model the resources of every stage of a

pipeline explicitly; one single unit to represent the first stage will do. Any

operation occupying the first stage of a pipeline is guaranteed the right to

proceed to subsequent stages in subsequent clocks.

1) a = b

2) c = d

3) b = c

4) d = a

5) c = d

6) a = b

Figure 10.5: A sequence of assignments exhibiting data

dependences

8. Exercises for Section 10.2

Exercise 1 0 . 2 . 1 : The assignments in Fig. 10.5 have

certain dependences. For each of the following pairs of statements, classify

the dependence as (i) true de-pendence, (n) antidependence, (Hi)

output dependence, or (iv) no dependence (i.e., the instructions can

appear in either order):

a)

Statements (1)

and (4).

b)

Statements (3)

and (5).

c)

Statements (1)

and (6).

d)

Statements (3)

and (6).

e)

Statements (4)

and (6).

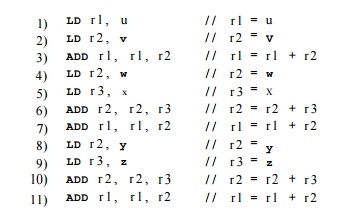

Exercise 10 . 2 . Evaluate the expression ((u+v) + (w+x)) + (y+z)

exactly as do not 2: parenthesized (i.e., use the commutative or associative

laws to reorder the additions). Give register-level machine code to provide the

maximum possible parallelism.

Exercise 10 . 2 . 3 : Repeat

Exercise 10.2.2 for the following expressions:

a) (u + (v + (w + x))^j + (y + z).

b) (u + (v + w)) + (x + {y + z)).

If instead of maximizing the parallelism, we minimized the number

of registers, how many steps would the computation take? How many steps do we

save by using maximal parallelism?

Exercise 1 0 . 2 . 4 : The expression of Exercise 10.2.2 can be

executed by the sequence of instructions shown in Fig. 10.6. If we have

as much parallelism as we need, how many steps are needed to execute the

instructions?

Figure 10.6: Minimal-register implementation of an

arithmetic expression

Exercise 1 0 . 2 . 5 : Translate the code fragment discussed in Example 10.4, using

the CM0VZ conditional copy instruction of Section 10.2.6. What are the

data dependences in your machine code?

Related Topics