Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Assessment of Genetic Disorders in Obstetrics and Gynecology

Prenatal Screening

PRENATAL SCREENING

Obstetricians are responsible for

determining if a woman is at increased risk for fetal abnormalities, and for

describ-ing and offering appropriate prenatal screening or diag-nostic tests. The purpose of prenatal genetic screening is

todefine the risk for a genetic disease in a low-risk population.

screening

test differs from a

diagnostic test in thatscreening

tests only assess the risk that a child will have a genetic disease; they

cannot confirm or rule out the presence of the dis-ease. A diagnostic test is

given if a screening test is positive, to assess whether the disease is present

or absent in the developing fetus. Genetic screening tests are routinely

offered to allwomen to detect neural tube defects (NTDs), Down syn-drome, and

trisomy 18. In addition, individuals of certain ethnic groups can be tested to

detect whether they carry a gene for a particular disorder.

First-Trimester Screening

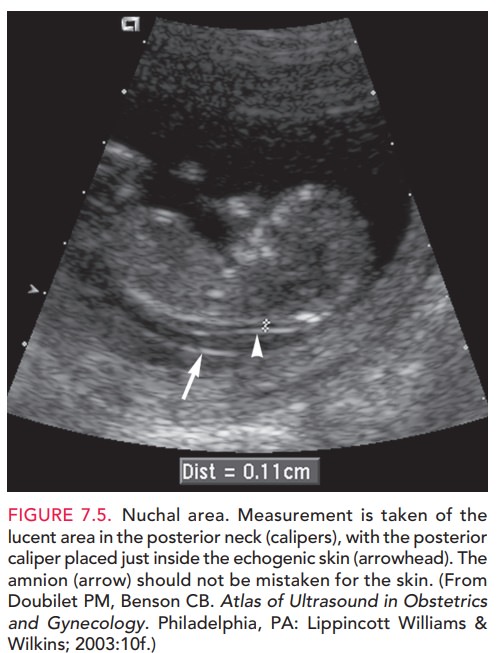

First-trimester screening tests are used to assess the risk of Down syndrome, trisomy 18, and trisomy 13 in a devel-oping fetus. First-semester serum screening for Down syndrome consists of tests for levels of two biochemical markers: free or total human chorionic gonadotropin(hCG) and pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A). An elevated level of hCG (1.98 of the medianobserved in euploid pregnancies [MoM]) and a decreased level of PAPP-A (0.43 MoM) have been associated with Down syndrome. An ultrasonographic marker for Down syndrome is the size of the nuchal transparency (NT), a fluid collection at the back of the fetal neck that can be seen between 10 and 14 weeks of gestation (Fig. 7.5). An increase in the size of the NT between 10 4/7 and 13 6/7 weeks of gestation is recognized to be an early presenting feature of a variety of chromosomal, genetic, and struc-tural abnormalities. When used alone, NT measurement has a detection rate for Down syndrome of 64% to 70%. Combining NT measurement with the other first-trimester biochemical markers yields an 82% to 87% detection rate of Down syndrome, with a 5% false-positive rate, which of her pregnancy.

Women who have

had first-trimester screening for aneuploidy should not undergo independent

second-trimester serum screening in the same pregnancy. When these test results

are interpreted independently, the false-positive rates are additive, leading

to many more unnecessary invasive procedures (11% to 17%). After

first-trimester screening, subsequent second-trimester Down syndrome screening

is not indicated, unless it is being performed as a component of an integrated

test (explained below), stepwise sequential, or contingent sequential test.

TRIPLE AND QUADRUPLE SCREENING TESTS

An association between low

maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels

and Down syndrome wasreported in 1984. In the 1990s, hCG and unconjugated

estriol were used in combination with maternal serum AFP to improve the

detection rates for Down syndrome and trisomy 18. The average maternal serum AFP

level in Down syndrome pregnancies is reduced to 0.74 MoM. Intact hCG is

increased in affected pregnancies, with an average level of 2.06 MoM, whereas

unconjugated estriol is reduced to an average level of 0.75 MoM. When the lev-els of all three markers (triple screen) are used to modify the

maternal age-related Down syndrome risk, the detection rate for Down syndrome

is approximately 70%; approximately 5% of all pregnancies will have a positive

screen result. Typically,the levels of all three markers are reduced when

the fetus has trisomy 18. Adding inhibin

A to the triple screen (quad-ruple

screen) improves the detection rate for Down syndrometo approximately 80%. The

median value of the maternalinhibin A level is increased at 1.77 MoM in Down

syn-drome pregnancies, but inhibin A is not used in the calcu-lation of risk

for trisomy 18. These biochemical screening tests are performed at 15 to 20

weeks of gestation.

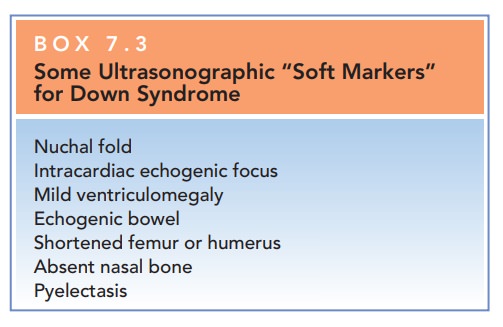

ULTRASOUND SCREENING

In the

second trimester, gross abnormalities, such as cardiac defects, as well as a

group of subtle sonographic markers (soft markers) may be associated with an

increased risk for Down syndrome in certain women (Box

7.3). Although findings of soft markers donot significantly increase the risk

of Down syndrome, they should be considered in the context of first-trimester

screening results, patient’s age, and history. The signifi-cance of

ultrasonographic markers identified by a second-trimester ultrasound

examination in a patient who has had a negative first-trimester screening test

result is unknown. Studies indicate that the highest detection rate is achieved

with systematic combination of ultrasonographic markers and gross anomalies,

such as thick nuchal fold or cardiac defects. However, an abnormal

second-trimester ultrasound finding identifying a major congenital anomaly

significantly increases the risk of aneuploidy and warrants further coun-seling

and the offer of a diagnostic procedure.

Box 7.3

Some Ultrasonographic “Soft Markers” for Down Syndrome

Nuchal fold

Intracardiac echogenic focus

Mild ventriculomegaly

Echogenic bowel

Shortened femur or humerus

Absent nasal bone

Pyelectasis

SCREENING FOR NTDS

Maternal serum AFP is also used to screen for NTDs, congenital structural abnormalities of the brain and vertebral column. NTDs occur in approximately 1.4–2 per 1000 births in the United States and are the second most common major con-genital abnormality worldwide (cardiac malformations are the most common). Maternal serum AFP evaluation is an effective screening test for NTDs and should be offered to all pregnant women, unless they plan to have amniotic AFP measurement as part of prenatal diagnosis for chromosomal abnormalities or other genetic diseases. Most affected preg-nancies can be identified by an elevated maternal serum AFP level, defined as 2.5 MoM for a singleton pregnancy. Womenwith a positive screening test should receive an ultrasound examination to detect identifiable causes of false-positive results (e.g., fetal death, multiple gestation, underestimate of gestational age) and for targeted study of fetal anatomy for NTDs and other defects associated with elevated mater-nal serum AFP.

Approximately 90% of newborns

with NTDs are born to women not offered amniocentesis because they have no

family or medication history that would indicate them to be at increased risk. Folic acid has been shown to prevent

recurrence and occurrence of neural tube defects. Becausemost individuals at increased risk do not know it until they

have an affected child, all women should be advised to take a vitamin that

contains at least 0.4 mg of folic acid prior to conception. Forwomen who

previously have had a child with a neural tube defect, the recommended dose is

4 mg daily.

Integrated Screening

The results of both

first-trimester and second-trimester screening and ultrasound can be combined

to increase their ability to detect Down syndrome. This“integrated”approach to

screening uses both the first-trimester and second-trimester markers to adjust

a woman’s age-related risk of having a child with Down syndrome. The

results are reported onlyafter both first-trimester and second-trimester

screening tests are completed. Integrated screening provides the highest

sensitivity with the lowest false-positive rate. The lower false-positive rate

results in fewer invasive tests and, thus, fewer procedure-related losses of

normal pregnancies. Although some patients value early screening, others are

willing to wait several weeks if doing so results in an improved detection rate

and less chance that they will need an invasive diagnostic test. Concerns about

integrated screening include possible patient anxiety generated by hav-ing to

wait 3 to 4 weeks between initiation and comple-tion of the screening and the

loss of the opportunity to consider CVS if the first-trimester screening

indicates a high risk of aneuploidy.

Related Topics