Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Health Care of the Older Adult

Physical Aspects of Aging

PHYSICAL

ASPECTS OF AGING

Cardiovascular System

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the aged. The heart valves become thicker and stiffer, and the heart muscle and ar-teries lose their elasticity. Calcium and fat deposits accumulate within arterial walls, and veins become increasingly tortuous. Although function is maintained under normal circumstances, the cardiovascular system has less reserve and responds less effi-ciently to stress. The maximum cardiac output decreases by about 25% from age 20 to age 80. Under conditions of stress, both the maximum cardiac output and the maximum HR di-minish gradually. The relationship between maximum HR and age is as follows:

Normal maximum HR for

age = 220 ŌłÆ age in years

Hypertension has been

shown to be a serious risk factor at all ages for cardiovascular disease and

stroke. A diagnosis of hyper-tension is made only after it has been confirmed

by at least two subsequent readings. In older people, hypertension is

classified as follows:

Isolated systolic

hypertension: the systolic reading exceeds140 mm Hg, and

the diastolic measurement is normal or near normal (less than 90 mm Hg)

Primary hypertension: the diastolic pressure is greater than orequal to 90 mm Hg regardless of

the systolic pressure Secondary

hypertension: hypertension that can be attributed toan underlying cause

Cardiovascular dysfunction may manifest as congestive heart failure,

coronary artery disease, arteriosclerosis, hypertension, in-termittent

claudication (leg pain caused by walking), peripheral vascular disease,

orthostatic hypotension, dysrhythmias, cerebro-vascular accidents (strokes), or

myocardial infarction (heart attack).

Heart failure (HF) is

the number one cause of hospitalization among Medicare recipients and is a

major cause of morbidity and mortality among the elderly population in the

United States. Older patients often present with different symptoms than those

seen in younger patients. Typically, younger persons present for care with the

symptoms of exertional dyspnea, or-thopnea, and peripheral edema, whereas older

patients typically report fatigue, nausea, and abdominal discomfort. In the

younger population, men are more prone to HF, but in the el-derly population

far greater numbers of women develop it. De-pending on its cause, HF can

require various forms of therapy. The current standard of therapy for HF

includes diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors)

and, digoxin. Several large studies have also indicated that carefully

monitored, low-dose beta-blockers and spironolactone can de-crease mortality

(Rittenhouse, 2001).

Cardiovascular health can be promoted by regular exercise, proper diet,

weight control, regular blood pressure measure-ments, stress management, and

smoking cessation. To avoid light-headedness, fainting, and possible falls caused

by orthostatic hypotension, the older person should be counseled to rise slowly

(from a lying, to a sitting, to a standing position); to avoid strain-ing when

having a bowel movement; and to consider having five or six small meals each

day, rather than three, to minimize the hypotension that can occur after a

large meal. Extremes in tem-perature should be avoided, including hot showers

and whirlpool baths. Yard work should be limited to no more than 20 minutes on

hot summer days. Exposure to wind or cold weather also should be avoided

because of the risk of dizziness or falling asso-ciated with slower adjustments

of blood pressure. If an individ-ual experiences dependent edema as the day

progresses, the use of elastic compression stockings helps to minimize venous

pooling.

Respiratory System

Age-related changes in the respiratory system affect lung capacity and

function and include increased anteroposterior chest diame-ter, osteoporotic

collapse of vertebrae resulting in kyphosis (in-creased convex curvature of the

spine), calcification of the costal cartilages and reduced mobility of the

ribs, diminished efficiency of the respiratory muscles, increased lung

rigidity, and decreased alveolar surface area. Increased rigidity or loss of

elastic recoil in the lung results in increased residual lung volume and

decreased vital capacity. Gas exchange and diffusing capacity are also

di-minished. Decreased cough efficiency, reduced ciliary activity, and

increased respiratory dead space make the older person more vulnerable to

respiratory infections.

Health promotion activities that help elderly persons maintain adequate

respiratory function include regular exercise, appropri-ate fluid intake,

pneumococcal vaccination, yearly influenza im-munizations, and avoidance of

people who are ill. As with people of all ages, smoking cessation and frequent

hand hygiene are pru-dent health practices. Hospitalized older adults should be

fre-quently reminded to cough and take deep breaths, particularly

postoperatively, because their decreased lung capacity and de-creased cough

efficiency predispose them to respiratory infections and atelectasis.

Integumentary System

The functions of the

skin include protection, temperature regu-lation, sensation, and excretion.

With aging, changes occur that affect the function and appearance of the skin.

The epidermis and dermis become thinner. Elastic fibers are reduced in number,

and collagen becomes stiffer. Subcutaneous fat diminishes, particu-larly in the

extremities. Decreased numbers of capillaries in the skin result in diminished

blood supply. These changes cause a loss of resiliency and wrinkling and

sagging of the skin. Hair pig-mentation decreases, resulting in gradual

graying. The skin be-comes drier and susceptible to irritations because of

decreased activity of the sebaceous and sweat glands. These changes in the

integument reduce tolerance to extremes of temperature and to exposure to the

sun.

Strategies to promote

healthy skin function include avoiding exposure to the sun, using a lubricating

skin cream, avoiding long soaks in the tub, and maintaining adequate intake of

water (8 to 10 eight-ounce glasses per day).

Reproductive System

Ovarian production of estrogen and progesterone ceases with menopause.

Changes occurring in the female reproductive sys-tem include thinning of the

vaginal wall, along with a narrowing in size and a loss of elasticity;

decreased vaginal secretions, result-ing in vaginal dryness, itching, and

decreased acidity; involution (atrophy) of the uterus and ovaries; and

decreased pubococcygeal muscle tone, resulting in a relaxed vagina and

perineum. These changes contribute to vaginal bleeding and painful intercourse.

In older men, the penis and testes decrease in size, and levels of

androgens diminish. Erectile dysfunction may develop with concomitant

cardiovascular disease, neurologic disorders, dia-betes, or even respiratory

disease, which limits exercise tolerance.

Sexual desire and activity decline but do not disappear. The use of

water-based lubricants can help prevent painful intercourse. Local estrogen

replacement intravaginally enhances vaginal tissue without the risks and side

effects of oral estrogen. Several modal-ities are available for treatment of

erectile dysfunction, which is linked to cardiovascular, neurologic, endocrine,

or occasionally psychological dysfunction. The use of vacuum penile pumps,

local injection or placement of vasostimulating medication into the ure-thral

opening, and use of an oral medication, sildenafil citrate (Vi-agra), have all

proved effective for some patients. Sildenafil citrate is contraindicated in

patients who are taking oral nitrates.

If significant sexual

dysfunction is present, referral to a gyne-cologist or urologist is warranted.

For both men and women, maintenance of a daily physical exercise routine

promotes en-hanced sexual performance.

Genitourinary System

The genitourinary system continues to function adequately in older

people, although there is a decrease in kidney mass, pri-marily because of a

loss of nephrons. Changes in kidney function include a decreased filtration

rate, diminished tubular function with less efficiency in resorbing and

concentrating the urine, and a slower restoration of acidŌĆōbase balance in

response to stress. Older women often suffer from stress or urge incontinence,

or both. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (enlarged prostate gland), which is a

common finding in older men, causes a gradual in-crease in urine retention and

overflow incontinence. Prostate can-cer, a slow-growing cancer, is most often

seen in men older than

70 years of age. Kidney and bladder cancers are most frequently seen

after the age of 50 years. Smoking is known to be a primary causative agent of

these carcinomas.

Adequate consumption of fluids is important to reduce the risk of

bladder infections and urinary incontinence. Other healthy habits include

having ready access to toilet facilities and voiding every 2 to 3 hours while

awake. Avoidance of bladder-irritating substancesŌĆösuch as caffeinated,

carbonated, and acidic beverages, Nutra-sweet, and alcoholŌĆöwill greatly reduce

urinary urgency and frequency. Water intake should be increased to avoid

concentrated urine, which causes urinary urgency.

Pelvic floor exercises,

first described by Kegel (1948), can also be extremely useful in reducing the

symptoms of stress and urge incontinence. Teaching the patient how to do the

exercises be-gins with identifying the pubococcygeus muscle, which is the same

muscle used to hold back flatus or to voluntarily stop the flow of urine without

contracting the abdomen, buttocks, or inner thigh muscles. The pelvic muscles

are first tightened and then relaxed, maintaining a 5-second contraction with

10-second rest intervals. This exercise should be routinely practiced for 30 to

80 repetitions each day; additional repetitions are discouraged because of the

risk of fatigue of the muscle. Because achieving bet-ter muscle control takes

at least several months to accomplish, the elderly person is encouraged to

consistently perform the exercises. To maintain pubococcygeus muscle control,

these daily exercises must continue indefinitely. The use of biofeedback to

confirm the correct execution of these exercises increases their effective-ness

significantly.

As menopause approaches,

a womanŌĆÖs circulating estrogen de-creases, and, as a result, the pelvic floor

is deprived of its needed blood supply and nutrients. This causes increasing

stress and urge incontinence. Through the use of biofeedback-assisted pelvic

muscle exercise, an individual can successfully regain bladder function. These

exercises are also recommended for men with dribbling incontinence related to

prostatectomy. The nurse in-structs the patient to tighten the rectal sphincter

until the penis and testes slightly lift. Frequent repetition produces the

desired muscle tone.

Constipation can be a

major factor contributing to urinary in-continence. The patient is encouraged

to eat a high-fiber diet, drink adequate fluids, and increase mobility to

promote regular bowel function.

Urinary tract infections are prevalent in older women. The reasons

include the effects of decreased estrogen, which shortens the urethral length,

allowing easier passage of bacteria into the bladder; less overall fluid

consumption, which causes a concen-trated urine in which bacteria can

proliferate; and the introduc-tion of bacteria from the rectum as a result of

poor bathroom hygiene secondary to impaired mobility and joint changes.

Lim-ited range of motion of the arm and limited hand dexterity often result in

a womanŌĆÖs cleansing the perineal area in a back-to-front motion, causing

bacteria such as Escherichia coli to

be introduced to the urethral meatus and thus into the bladder (Degler, 2000b).

Gastrointestinal System

The older adult is at increased risk for impaired nutrition. Peri-odontal disease leading to tooth decay and loss of teeth is com-mon. Salivary flow diminishes, and the older person may experience a dry mouth. A preference for sweet and salty foods results from a decrease of taste receptors. Major complaints often center on feelings of fullness, heartburn, and indigestion. Gastric motility may decrease, resulting in delayed emptying of stomach contents.

Diminished secretion of acid and pepsin reduces the absorption of iron,

calcium, and vitamin B12. Absorption of nutrients in the small intestine also appears to

diminish with age. The function of the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas is

generally maintained, although absorption and tolerance to fat may decrease.

The inci-dence of gallstones and common bile duct stones increases

pro-gressively with advancing years.

Difficulty in swallowing, or dysphagia, affects 1 in 17 people,

including 6.2 million Americans over the age of 60 years, with 300,000 to

600,000 new cases diagnosed each year. It is a serious condition that can be

life-threatening. It results from interrup-tion or dysfunction of neural

pathways, such as can occur with stroke. It may also develop from dysfunction

of the striated and smooth muscles of the gastrointestinal tract in up to 50%

of pa-tients with ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease and in those with conditions such as

multiple sclerosis, poliomyelitis, and amyotrophic lateral scle-rosis (Lou

GehrigŌĆÖs disease). Aspiration of food or fluid is the most serious complication

and can occur in the absence of cough-ing or choking (Galvan, 2001).

Constipation is common

in aged people. When mild, the symptoms involve abdominal discomfort and

flatulence, but more serious consequences include fecal impaction that

contributes to diarrhea around the impaction, fecal incontinence, and

obstruc-tion. Predisposing factors for constipation include lack of dietary

bulk, prolonged use of laxatives, the use of some medications, inactivity,

insufficient fluid intake, and excessive dietary fat. Another factor may be

ignoring the urge to defecate.

Gastrointestinal health

promotion practices include receiving regular dental care; eating small,

frequent meals; avoiding heavy activity after eating; eating a high-fiber,

low-fat diet; ingesting an adequate amount of fluids; establishing regular

bowel habits; and avoiding the use of laxatives and antacids. Understanding

that there is a direct correlation between loss of smell and taste per-ception

and food intake helps caregivers to intervene to maintain elderly patientsŌĆÖ

health.

Nutritional Health

The social, psychological, and physiologic functions of eating

in-fluence the dietary habits of the aged person. Decreased physical activity

and a slower metabolic rate reduce the number of calo-ries needed by the older

adult to maintain an ideal weight. Apathy, immobility, depression, loneliness,

poverty, inadequate knowl-edge, lack of oral health, and lack of taste

discrimination also con-tribute to suboptimal nutrient intake. Budgetary

constraints and physical limitations may impair food shopping and meal

prepa-ration. Education regarding healthy versus ŌĆ£empty-calorieŌĆØ foods is

helpful.

Health promotion teaching includes encouraging a diet that is low in

sodium and saturated fats and high in vegetables, fruits, and fish. The older

adult requires a variety of foods to maintain balanced nutrition. No more than

20% to 25% of dietary calo-ries should be consumed as fat. Reducing salt intake

is also advo-cated, because sodium reduction has been shown to correct

hypertension in some people. Protein intake should remain the same in later

adulthood as in earlier years. Carbohydrates, a major source of energy, should

supply the diet with 55% to 60% of the daily calories. Simple sugars should be

avoided and complex car-bohydrates encouraged. Potatoes, whole grains, brown

rice, and fruit provide the person with minerals, vitamins, and fiber and

should be encouraged. Drinking 8 to 10 eight-ounce glasses of water per day is

recommended unless contraindicated by a medical condition. A multivitamin each day helps

to maintain daily nutritional needs.

Sleep

Sleep disturbances frequently occur in older people, affecting more than

50% of adults 65 years of age or older. The elderly often experience variations

in their normal sleepŌĆōwake cycles, and the lack of quality sleep at night often

creates the need for napping during the day. Laboratory screening can help to

rule out disease processes that might be affecting an older personŌĆÖs ability to

sleep at night. If a spouse notes excessive snoring, a sleep study is

indi-cated to rule out sleep apnea. The nurse can recommend prudent sleep

hygiene behaviors such as avoiding daytime napping, eating a light snack before

bedtime, and decreasing the overall time in bed to adjust for the fewer hours

of sleep needed than when the patient was younger (Grandjean & Gibbons,

2000).

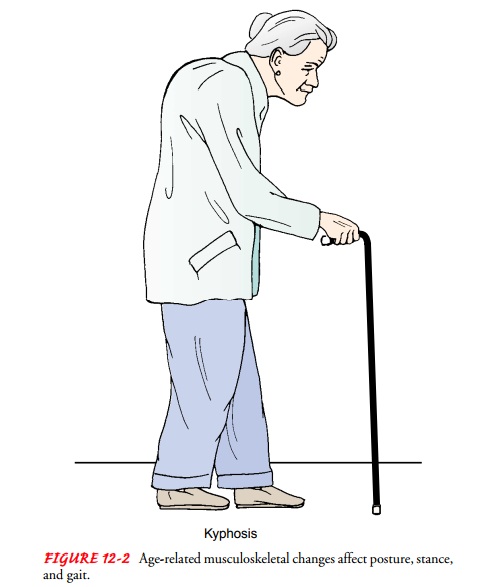

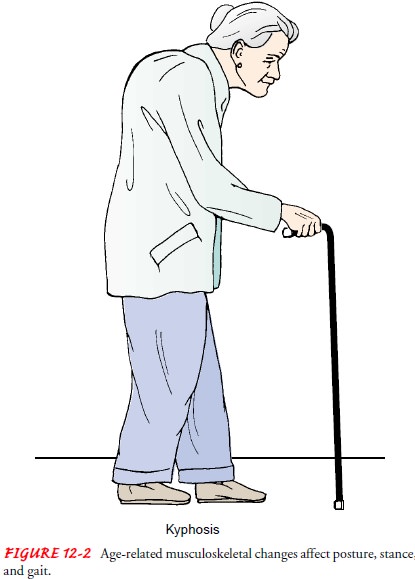

Musculoskeletal System

A gradual, progressive decrease in bone mass begins before the age of 40

years. Excessive loss of bone density results in osteoporosis, which affects

both older men and women but is most prevalent in postmenopausal women. It is

also seen in older men who are receiving hormone treatments for prostate

cancer. A higher inci-dence is found among northern Europeans and Asians. Its

typi-cal form is associated with inactivity, inadequate calcium intake, loss of

estrogens, and a history of cigarette smoking. The danger of fracture as a

result of bone reabsorption is especially high for the dorsal portion of the

vertebra, humerus, radius, femur, and tibia. A loss of height occurs in later

life as a result of osteoporotic changes of the spine, kyphosis (excessive

convex curvature of the spine), and flexion of the hips and knees. These

changes negatively affect mobility, balance, and internal organ function (Fig.

12-2).

The muscles diminish in

size and lose strength, flexibility, and endurance with decreased activity and

advanced age. Back pain is common. Beginning in middle age, the cartilage of

joints pro-gressively deteriorates. Degenerative joint disease is found in

everyone past the age of 70 years.

Calcium supplements,

vitamin D, fluoride, estrogens, and weight-bearing exercises are often

prescribed for the person who is at high risk for or already has osteoporosis.

Although osteo-porosis cannot be reversed, the disease process can be slowed. A

bone density test is the gold standard to assess for osteoporosis. Once it is

diagnosed and treatment begun, yearly follow-up de-terminations of the bone

density level are indicated. For skeletal health, the nurse can recommend the following

(Scheiber & Torregrosa, 2000):

ŌĆó

A high calcium intake, 1500 mg/day. Dairy products

and dark green vegetables are excellent sources, as are soups and broths made

with a soup bone and cooked with added vine-gar to leach calcium from the bone.

Calcium supplements can be recommended to ensure that the daily calcium in-take

is adequate.

ŌĆó

A low-phosphorus diet. A calcium-to-phosphorus

ratio of 1:1 is ideal; red meats, cola drinks, and processed foods that are low

in calcium and high in phosphorus are avoided.

ŌĆó

Weight-bearing exercise. The pull of muscle

insertions on the long bones strengthens the muscles and retards calcium

resorption.

ŌĆó

Reduction of caffeine and alcohol. This assists in

stopping further demineralization and renal excretion of calcium.

ŌĆó

Smoking cessation.

ŌĆó

Selective estrogen receptor modulators, such as

raloxifene (Evista), preserve bone mineral density without estrogenic effects

on the uterus. This medication is indicated for both prevention and treatment

of osteoporosis. Although hor-mone replacement therapy (HRT) has been the

mainstay of therapy for perimenopausal women, recent studies have demonstrated

greater risks than previously recognized (Chen, Weiss, Newcomb, Barlow &

White, 2002).

ŌĆó

The bisphosphate drugs (e.g., Fosamax, Actonel).

These drugs bind to mineralized bone surfaces to inhibit osteo-clastic activity

and promote bone formation.

Muscle strength and flexibility can be enhanced with a pro-gram of

regular exercise. The axiom ŌĆ£use it or lose itŌĆØ is very rel-evant when

considering the physical capacity of aged people. The nurse plays an important

role by encouraging older adults to participate in a regular exercise program.

Regular exercise in-creases the strength and efficiency of heart contractions,

im-proves oxygen uptake by cardiac and skeletal muscles, reduces fatigue,

increases energy, and reduces cardiovascular risk factors. Muscle endurance,

strength, and flexibilityŌĆöall outcomes of regular exerciseŌĆöalso help to promote

independence and psy-chological well-being. Aerobic exercises are the

foundation of programs of cardiovascular endurance conditioning. A physical

examination by a physician or nurse practitioner is necessary be-fore

initiating an exercise program, and older persons should perform exercises in

moderation and use short rests to avoid undue fatigue. Swimming and brisk

walking are often recom-mended because they are managed easily and usually are

enjoyed by the older person.

Information about the nature and time course of menopause-associated bone

loss through early markers may be used to help to preserve bone and thus stop

the natural sequelae of osteoporosis. A nurse-led research team used frequent

sequential serum mark-ers to confirm these changes and found a correlation with

elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and concentrations of follicle-stimulating

hormone as a marker for vitamin K status. Therefore, perimenopausal women with

elevated ALP can be targeted for health promotion to preserve bone density

(Lukacs, 2000).

Nervous System

The structure and function of the nervous system change with ad-vanced

age, and a reduction in cerebral blood flow accompanies nervous system changes.

The loss of nerve cells contributes to a progressive loss of brain mass, and

the synthesis and metabolism of the major neurotransmitters are also reduced.

Because nerve impulses are conducted more slowly, older people take longer to

respond and react. The autonomic nervous system performs less efficiently, and

postural hypotension, which causes the person to lose consciousness or feel

lightheaded on standing up quickly, may occur. Cerebral ischemia with related

lightheadedness may interfere with mobility and safety. The nurse advises the

person to allow a longer time to respond to a stimulus and to move more deliberately.

Homeostasis is more difficult to maintain, but in the absence of pathologic

changes, the older person functions ade-quately and retains cognitive and

intellectual abilities.

Mental function is

threatened by physical or emotional stresses. A sudden onset of confusion may

be the first symptom of an in-fection or change in physical condition

(pneumonia, urinary tract infection, medication interactions, dehydration, and others).

A slowed reaction time

places the older person at risk for falls and injuries, including driving

errors. Compared with the per-mile fatality rate for drivers aged 25 to 69

years, that for drivers 70 years of age and older is nine times as high. When

an elderly person has been witnessed driving unsafely, he or she should re-ceive

a driving fitness evaluation; this is often administered by an occupational

therapist in conjunction with a neuropsychologist, who can help with the more

detailed cognitive testing (Dolinar, McQuillen, & Ranseen, 2001).

Sensory System

Sensory losses with old

age affect all sensory organs and can be devastating to the person who cannot

see to read or watch televi-sion, hear conversation well enough to communicate,

or dis-criminate taste well enough to enjoy food.

SENSORY LOSSES VERSUS SENSORY DEPRIVATION

Sensory losses can often be helped by assistive devices such as glasses

and hearing aids. In contrast, sensory deprivation is the ab-sence of stimuli

in the environment or the inability to interpret existing stimuli (perhaps as a

result of a sensory loss). This depri-vation can lead to boredom, confusion,

irritability, disorienta-tion, and anxiety. Meaningful sensory stimulation

offered to the older person is often helpful in correcting this problem. One

sense can substitute for another in observing and interpreting stimuli. The

nurse can enhance sensory stimulation in the envi-ronment with colors,

pictures, textures, tastes, smells, and sounds. The stimuli are most meaningful

if they are interpreted to the older person and if they are changed often.

Cognitively impaired persons respond well to touch and to familiar music.

VISION

As new cells form on the

outside surface of the lens of the eye, the older central cells accumulate and

become yellow, rigid, dense, and cloudy, leaving only the outer portion of the

lens elas-tic enough to change shape (accommodate) and focus at near and far

distances. As the lens becomes less flexible, the near point of focus gets

farther away. This condition, presbyopia,

usually begins in the fifth decade of life, and requires the wearing of reading

glasses to magnify objects. In addition, the yellowing, cloudy lens causes

light to scatter and makes the older person sensitive to glare. The ability to

discern blue from green de-creases. The pupil dilates slowly and less

completely because of increased stiffness of the muscles of the iris, so the

older person takes longer to adjust when going to and from light and dark

en-vironments or settings and needs brighter light for close vision. Although

pathologic visual conditions are not part of normal aging, the incidence of eye

disease (most commonly cataracts, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and

age-related macular degen-eration) increases in older people.

Age-related macular degeneration, in its most severe forms, is the most

common cause of blindness in adults older than 55 years of age in the United

States, and it is estimated to affect more than 10 million Americans. Risk

factors include sunlight exposure, cig-arette smoking, and heredity, and people

with fair skin and blue eyes are much more prone to the disease. Sunglasses and

hats with visors provide some protection. Yearly eye checkups ensure early

detection, which makes surgical correction much more success-ful. Optical aids

to magnify print and printed objects may help those already suffering from the

effects of macular degeneration to continue to read (Friberg, 2000).

HEARING

Presbycusis, a loss of the ability to hear

high-frequency tones at-tributed to irreversible inner ear changes, occurs in

midlife. Older people are often unable to follow conversation because tones of

high-frequency consonants (letters f, s, th, ch, sh, b, t, p) all sound alike.

Hearing loss may cause the older person to re-spond inappropriately,

misunderstand conversation, and avoid social interaction. This behavior may be

erroneously interpreted as confusion. Wax buildup or other correctable problems

may also be responsible for major hearing difficulties. A properly pre-scribed

and fitted hearing aid may be useful in reducing hearing deficits.

TASTE AND SMELL

Of the four basic tastes

(sweet, sour, salty, and bitter), sweet tastes are particularly dulled in older

people. Blunted taste may con-tribute to the preference for salty, highly

seasoned foods, but herbs, onions, garlic, and lemon should be encouraged as

substi-tutes for salt to flavor food.

Related Topics