Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Health Care of the Older Adult

Environmental Aspects of Aging

ENVIRONMENTAL

ASPECTS OF AGING

About 95% of the elderly

live in the community, and 75% own their homes. In 1991, about 31% of elderly

persons were living alone (79% of these were women). In the 65 years and older

age group, half as many women as men were married and living with their

spouses: 40% of women compared with 74% of men. About 48% of the women older

than 65 years of age were wid-owed, compared with only 15% of the men. This

difference in marital status is a result of several factors: women have a

longer life expectancy than men do, women tend to marry older men, and women

tend to remain widowed, whereas men often remarry (U.S. Bureau of the Census,

2000).

Living Arrangement Options

Ideally, older persons do best in their own, familiar environment. But

adjustments to the environment may be required to allow the older adult to

remain in his or her own home or apartment. Sometimes, in order to enable them

to remain in their own home, an older adult or couple seek out family members

who might be willing to live in the home, or agree to board someone in

ex-change for completion of household chores.

Sometimes older adults or couples agree to move in with adult children.

This can be a rewarding experience as the children, their parents, and the

grandchildren interact and share household re-sponsibilities. It can also be

stressful, depending on the family dy-namics. Adult children and their older

parents may also choose to pool their financial resources by moving into a

house that has an attached “in-law suite.” This arrangement provides security

for the older adult along with privacy for both families.

Continuing Care Retirement Communities (CCRCs), are be-coming more

popular as the first of the baby boomers enter their retirement years. CCRCs

are retirement communities consisting of single-dwelling houses or apartments

for those individuals who are still able to manage all of their day-to-day

needs, assisted liv-ing apartments for those who need limited assistance with

their daily living needs, and skilled nursing services when continuous nursing

assistance is required. These communities usually con-tract for a large down

payment before the resident moves into the community. This payment allows the

individual or couple the option to reside in the community from the time of

total inde-pendence through the need for assisted or skilled nursing care. This

concept allows for decisions about living arrangements and health care to be

made before any decline in health status occurs. A CCRC also provides

continuity at a time in an older adult’s life when many other factors, such as

health status, income, and avail-ability of friends and family members, may be

changing.

Assisted living facilities are an option when physical or cogni-tive

changes require at least minimal supervision. Assisted living allows for a

degree of independence while providing minimal nursing assistance (eg,

administration of medication and coordi-nation of scheduled and acute care

medical assistance). Other ser-vices, such as laundry, cleaning, and meals, may

also be included.

Skilled nursing facilities offer continuous nursing care. Usu-ally, if

an older adult suffers a major health event such as a stroke, myocardial

infarction, or cancer and is hospitalized, Medicare will cover the cost of the

first 30 to 90 days in a skilled nursing facility if ongoing therapy is needed.

The stipulation for contin-ued Medicare coverage during this time is

documentation of per-sistent improvement in the required therapies, which most

often include physical therapy, occupational therapy, respiratory ther-apy, and

cognitive therapy. Some individuals choose to have nursing home insurance as a

means of paying, at least in part, for the cost of these services, should they

become necessary. When an individual’s financial resources become exhausted as

a result of prolonged nursing home care, the family, the institution, or both

may apply for Medicaid reimbursement. An increasing number of skilled nursing

facilities offer subacute care. This area of the fa-cility offers a high level

of nursing care and may either prevent the need for an individual to be

transferred to a hospital setting or allow a hospitalized individual to be

transferred back to the fa-cility sooner.

Life Care Plans

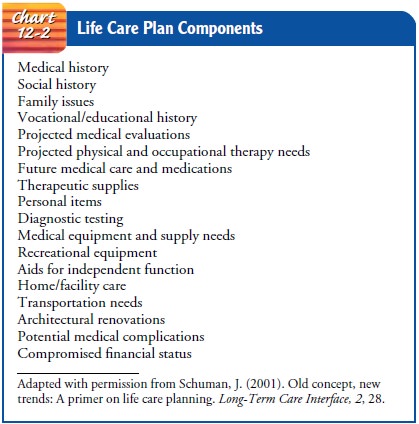

A life care plan is an individualized document that assesses and

eval-uates a client’s present and future health care and living needs. The

typical components of a life care plan are listed in Chart 12-2. Life care

plans were originally developed in 1981 as standardized, ef-ficient guidelines

for medical and ancillary quality-of-life services. A life care plan provides

valuable information regarding factors that can radically affect the

individual’s health care and quality of life. A life care plan is often

requested for individuals with cata-strophic injuries or illness (eg, traumatic

brain injury, amputa-tion, multiple sclerosis) who will require ongoing

rehabilitative

A life care plan may also serve as the blue-print

for what will be expected in long-term care. These plans provide a guideline of

anticipated patient care needs for families, insurance companies, attorneys,

discharge planners, case managers, and all medical and nursing professionals.

The cost of the life care plan varies, depending on the planner, the severity

of the injury or illness, and who is paying for the service, but the average

cost is currently between $5,000 and $20,000 (Schuman, 2001).

The Role of the Family

Planning for care and understanding the psychosocial issues confronting

the older person must be accomplished within the context of the family. If

dependency needs occur, the spouse often assumes the role of primary caregiver.

In the absence of the surviving spouse, an adult child usually assumes

caregiver responsibilities and may eventually need help in providing care and

support. Two common myths in American society are that adult children and their

aged parents are socially alienated and that adult children abandon their

parents when health and other dependency problems arise. Extensive research

refutes both of these beliefs. The family is an important source of sup-port

for older people (Fig. 12-3). Approximately 81% of elderly persons have living

children. Of those elders living alone, two thirds have at least one child

living within 30 minutes of their home, and 62% see at least one adult child

weekly (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000).

Social attitudes and

cultural values often dictate that adult children should provide services and

financial support and as-sume the burden of care if their aged parents are

unable to care for themselves. Illness creates special problems for people who

live alone. If community agencies or adult children are unable to pro-vide

care, elders are at high risk for institutionalization.

Regardless of the amount of responsibility and love an adult child exhibits toward dependent elderly parents, strains do de-velop if care continues for a long period. Research exploring the relationship between aged parents and their adult children shows that the quality of the parent–child relationship declines with the poor health of the parent. Under certain circumstances of high risk, strains in intergenerational relationships can result in elder abuse (Hoban & Kearney, 2000; Phillips, 2000; Tumolo, 2000).

Elder abuse is an active

or passive act or behavior that is harm-ful to the elderly person. Such behavior

includes physical vio-lence, personal neglect, financial exploitation,

violation of rights, denial of health care, and self-inflicted abuse.

Preventive action should be taken when strains are evident, before elder abuse

oc-curs. Interdisciplinary team members can be enlisted to help the caregiver

develop self-awareness, increased insight, and an un-derstanding of the aging

process. At the same time, community resources may be useful for both the aged

person and the care-giver (Geldmacher, Heck, & O’Toole, 2001).

Community Support Services

Many community supports

exist that help the older person main-tain independence. Informal sources of

help, such as family, friends, the mail carrier, church members, and neighbors,

can all keep an informal watch. Area Agencies on Aging perform many community

services, including telephone reassurance, friendly visitors, home repair

services, and home-delivered meals. Home-maker and chore services can be

obtained at an hourly rate through these agencies or through local community

nursing ser-vices. If a person is unable to pay, these services may be

subsidized through local and state funds.

Other community support

services are available to help the older person outside the home. Senior

centers have social and health promotion activities, and some provide a

nutritious noon-time meal. Adult day care facilities offer daily nursing care

and social opportunities; these services also enable family members to carry on

daily activities while the older person is at the day care center.

Home Health Care

Home care is often used as a means to prevent hospitalization for frail,

elderly outpatients or to shorten a hospital stay. It can also be used as a

high-tech substitute for hospitalization and can include the use of intravenous

therapy and other therapies previously de-livered in the acute care setting.

Home health care was the area of U.S. health care that saw the most rapid rate

of growth in the 1990s, and by the end of the 1990s it had come to represent

almost one tenth of the total Medicare budget. Rather than viewing home health

care as a means of controlling health care costs, the Federal government’s

Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS), formerly the Health Care

Financing Administration (HCFA), de-vised plans to limit the growth of home

health care services. The first system put into place to accomplish decreased

allocations for home health was called the Prospective Payment System (PPS) for

home care, implemented in 2000. Later came a means of quanti-fying needed home care,

called the Outcome and Assessment In-formation Set (OASIS). The OASIS rates

individual consumers of home health care in terms of their ability to perform

activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living

(IADLs). Nursing care and rehabilitation services requiring the ex-pertise of a

registered nurse and other health professionals were tra-ditionally paid for by

Medicare. With the advent of the PPS, limits on reimbursement may mean

consideration of alternative means of reimbursement for such services,

including private pay and health insurance products (HCFA, 2000; Plotkin &

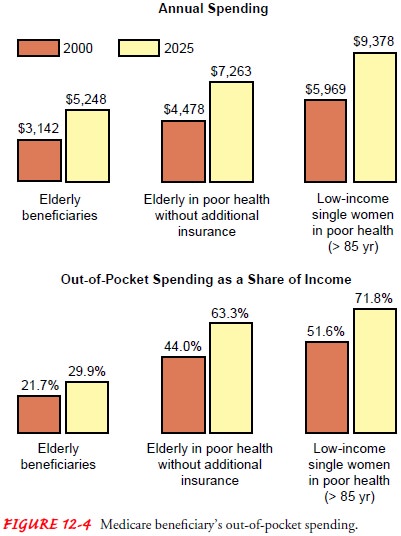

Roche, 2000; Nus baum, 2000). Figure 12-4 shows the estimated growth in

Medicare and out-of-pocket annual spending between 2000 and 2025.

Safety and Comfort in the Home Environment

Injuries rank seventh as a cause of death for older people. The nurse

can encourage lifestyle and environmental changes that older adults and their

families can adopt. Adequate lighting with mini-mal glare and shadow can be

achieved through the use of small area lamps, indirect lighting, sheer curtains

to diffuse direct sunlight, dull rather than shiny surfaces, and nightlights.

Sharply contrast-ing colors can be used to mark the edges of stairs. Grab bars

by the tub and toilet are useful. Loose clothing, improperly fitting shoes,

scatter rugs, small objects, and pets create hazards and increase the risk of

falls. A person functions best in familiar settings if furniture and objects

remain as unchanged as is safely possible.

Hospice Services

Hospice services are a dignified alternative to the chaos of the acute

care setting when a patient with an end-stage disease is not ex-pected to live

long. Hospice is a program of supportive and pal-liative services for dying

patients and their families that includes physical, psychological, social, and

spiritual dimensions of care. Under Medicare and Medicaid, all needed medical

and nursing services are provided to keep the patient as pain free and

comfort-able as possible. The family must agree to assist in the care of the

patient, and services are brought into the home as needed. Hos-pice services

may also be incorporated into the care of residents in long-term care

facilities and include care for end-stage dementia.

Hospice services that are provided in a person’s home also are rated via the OASIS system. Although this system can be very cumbersome and time-consuming in hospice care because of the many care providers involved, it can serve as an excellent tool with which nurses can assess the effects of particular services on specific patient outcomes (Plotkin & Roche, 2000).

Home care and hospice nurses are in a unique position to fa-cilitate

early discussions about a patient’s wishes and goals at the end of life. Too often,

discussion regarding end-of-life care is postponed until a crisis situation

occurs, making it difficult or im-possible for the patient to be an active

participant in the discus-sion. Home health nurses can assist the patient and

family with identifying available options and initiating conversation about

preparing an end-of-life plan (Norlander & McSteen, 2000).

Related Topics