Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Health Care of the Older Adult

Overview of Aging

Overview of Aging

DEMOGRAPHICS OF AGING

According to the National Center for Health Statistics, life ex-pectancy, the average number of

years that a person can be ex-pected to live, has risen dramatically over the

past century. In 1900, the average life expectancy was 47.3 years, but by 1998

that figure had increased to 76.7 years. According to data from the National

Vital Statistics System, in 1998 a 75-year old man could be expected to live

until the age of 85, and a 75-year old woman could be expected to live until

the age of 87 (National Center for Health Statistics, 2000).

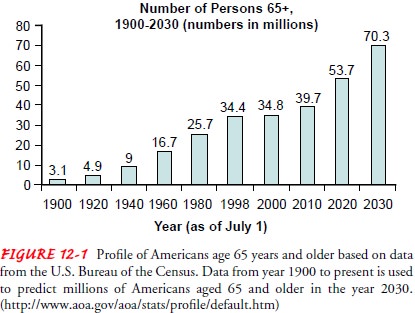

By 2030, people older

than 65 years of age will account for 22% of the population, compared with 13%

in 2001 (Fig. 12-1).

More than 70% of elders receive most of their care from infor-mal caregivers. Because many of the baby boomers (those born be-tween 1940 and 1960) tended to have children later in life, these children will face the competing demands of caring for their aging parents while caring for their own dependent children (Spillman, 2001).

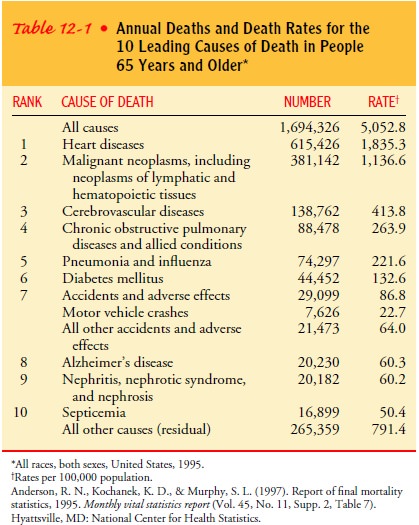

Although most older

adults enjoy good health, in national sur-veys as many as 40% of adults age 65

and older report disability. Chronic disease is the major cause of disability,

and heart disease, cancer, and stroke continued to be the three most

significant causes of death in persons 65 years of age and older in the United

States between 1980 and 1998 (Table 12-1). Alzheimer’s disease accounted for

almost 44,000 deaths in 1999 (National Center for Health Statistics, 2000).

HEALTH CARE COSTS OF AGING

There are serious concerns about whether there will be sufficient health services available as more and more persons in the United States become eligible for publicly funded health programs. The two major health programs in the United States are Medicare and Medicaid, both of which are overseen by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS), formerly the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA). Medicare is funded by the Federal government, whereas Medicaid is funded jointly by the Federal and state governments to provide health care for the poor. Medicaid is the dominant public payer of nursing home costs. Eligibility and costs for these services vary from state to state.

Medicare funding covered

32% of the costs of hospital services and 22% of the costs of physician

services in the United States in 1998. Nursing home care, in contrast, was

financed primarily by Medicaid (46%) and out-of-pocket payments (33%)(National

Center for Health Statistics, 2000).

ETHICAL AND LEGAL ISSUES AFFECTING THE OLDER ADULT

Loss of rights, victimization, and other grave problems face the person

who has made no plans for personal and property man-agement in the event of

disability or death. The advice and ser-vices of a competent attorney regarding

financial and personal issues can preserve future autonomy and

self-determination. The nurse as an advocate can encourage the older person to

prepare advance directives for future decision making in the event of

incapacitation (Plotkin & Roche, 2000).

A power of attorney is a legal agreement that authorizes a des-ignated

person to act in specific, outlined circumstances on be-half of the signer. This

is a form of voluntary guardianship, permission for which is freely granted

when the older person is competent. Unless stated otherwise, a power of

attorney is inval-idated on the incapacity of the signer. A durable power of

attor-ney is a similar agreement that continues even if the older person is

disabled or incapacitated. This power can include the autho-rization to make

financial or personal decisions, depending on the desires of the signer (Chart

12-1).

A trust is another

option that the competent older person can consider. In a trust, the person

designates someone to manage hisor her property, stipulates how and under what

circumstances the property will be managed, and designates a beneficiary. If

in-competency or disability occurs, management of the property is undertaken

according to the person’s wishes.

If no advance arrangement has been made, and the older per-son appears

unable to make decisions, anyone can

petition the court for a competency hearing. If the court rules that the

per-son is incompetent, the judge will appoint a guardian—a third party who is

given powers by the court to assume responsibility for making financial or

personal decisions for that person. There are two kinds of guardians: guardian

of the person and guardian of the estate. Because such a court action strips

the civil liberties and constitutional rights from the older person, a

potential for great harm exists. Safeguards include the following: (1) the

older person must be given notice, (2) he or she must be given anopportunity to

be legally represented, and (3) medical testimony can be cross-examined. A less

restrictive form of guardianship, called limited guardianship, transfers to the

appointed guardian only those powers or duties that the older person cannot

exercise. Although this alternative is not widely used, it remains an option.

An advance directive is a formal, legally endorsed document that

provides instructions for care (living will) or names a proxy de-cision maker

(durable power of attorney) and is to be implemented in the event of the

signer’s future decision-making incapacity. This written document must be

signed by the person and by two wit-nesses; a copy should be given to the

physician and incorporated into the medical record. The person must understand that

this doc-ument is not meant to be used only when certain (or all) types of

medical treatment are withheld; rather, it allows for a detailed de-scription

of all health care preferences, including full use of all available medical

interventions. The health care proxy has the au-thority to interpret the

patient’s wishes on the basis of the medical circumstances of the situation and

is not restricted to deciding only whether life-sustaining treatment can be

withdrawn or withheld.

In 1990, the Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA), a fed-erally

mandated law, was enacted to require patient education about advance directives

at the time of hospital admission, along with documentation of this education.

The PSDA is also man-dated in nursing homes to enhance resident autonomy by

in-creasing involvement in health care decision making. A growing body of

research indicates that nursing homes implement the PSDA more vigorously than

hospitals do. In both settings, how-ever, the documentation and placement of

advance directives in the medical record varies considerably from facility to

facility, as does the education of patients about advance directives. Processes

for fulfilling the requirements of the law are continuously being revised in

many facilities to promote compliance. The PSDA pro-vides no guidelines

regarding how often the advance directives of nursing home residents should be

reviewed. Continuing quality improvement programs that establish guidelines for

review are more likely to exist in nursing homes in which ethics committees are

present. The nurse can play a vital role in advocating for the patient when the

patient or a family member is unable to do so.

NURSING CARE OF OLDER ADULTS

Geriatrics, the study of old age, includes the physiology, pathol-ogy, diagnosis,

and management of the diseases of older adults. The broader field of gerontology, or the study of the aging

pro-cess, draws from the biologic, psychological, and sociologic sci-ences.

Because hospitalized patients are being discharged to home “quicker and sicker”

than ever before, nurses in all settings, in-cluding hospital, home care,

rehabilitation, and outpatient set-tings, need to be knowledgeable about

geriatric nursing principles and skilled in meeting the needs of elderly

patients.

Gerontologic or geriatric nursing is the

field of nursing thatspecializes in the care of the elderly. The Standards and Scope ofGerontological Nursing

Practice were originally developed in 1969by the American Nurses

Association; they were revised in 1976 and again in 1987. The nurse

gerontologist can be either a specialist or a generalist offering comprehensive

nursing care to older persons by combining the basic nursing process of

assessment, diagnosis, plan-ning, implementation, and evaluation with a

specialized knowledge of aging. Currently, nurses from all nursing programs,

including vocational programs (LPN/LVN), traditional hospital programs, and

college degree programs (ADN/BSN), as well as master’s pre-pared advanced

practice nurses (clinical nurse specialists, nurse practitioners, and nurse

anesthetists), care for older adults.

Gerontologic nursing is provided in acute care, skilled and as-sisted

living, community, and home settings. Its goals include promoting and

maintaining functional status and helping older adults to identify and use

their strengths to achieve optimal independence. The nurse helps the older

person to maintain dig-nity and maximum autonomy despite physical, social, and

psy-chological losses. The nurse who becomes certified in gerontologic nursing

has specialized knowledge in the acute and chronic changes specific to older

people. The use of advanced practice nurses (APNs) in long-term care has proved

to be very effective: when APNs using current scientific knowledge about

clinical problems interface with nursing home staff, significantly less

de-terioration in affect and overall health issues has been demon-strated

(Ryden et al., 2000).

Because old age is a normal occurrence that encompasses all experiences

of life, care and concern for the elderly cannot be lim-ited to one discipline,

but is best provided through a cooperative effort. An interdisciplinary team,

through comprehensive geri-atric assessment, can combine expertise and

resources to provide insight into all aspects of the aging process. Nurses

collaborate with the interdisciplinary team to obtain non-nursing services and

provide a holistic approach to care.

Related Topics