Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Intrapartum Care

Normal Labor And Delivery: General Management

NORMAL LABOR AND DELIVERY

Ideally, a pregnant woman has a

principal, designated health care provider. Beginning with admission to the

labor and delivery area, the obstetric team monitors the patient’s progress.

Once the patient is in active labor, her provider should be readily available.

General Management

AMBULATION AND POSITION IN LABOR AND AT DELIVERY

Walking may be more comfortable

than being supine dur-ing early labor. Women in early labor are confined to bed

if they are too uncomfortable to move about safely or if care

Supine

labor is common in the United States. The left lateral position keeps the

uterus off the infe-rior vena cava; this obstructs venous return, thence

cardiac output, leading to hypotension (supine hypotensive syn-drome). Thedorsal

lithotomy positionis most commonly usedfor spontaneous and operative

vaginal delivery in the United “birthing chairs,” on labor balls, or in

variously configured tubs of warm water.

FLUID MANAGEMENT AND ORAL INTAKE

Because labor is associated with

decreased gastrointestinal peristalsis, there is concern about aspiration

during the administration of anesthesia. Patients in active labor should avoid

oral ingestion of anything except clear fluids (sips only), occasional ice

chips, and preparations for moisten-ing the mouth and lips.

When oral intake is not possible

or is insufficient, intravenous therapy with 1⁄2 normal saline or D5

1⁄2 normal saline is indicated. Normal saline can be used if

increased oncotic pressure is desired, but lactated fluids are gener-ally

contraindicated because of the metabolic acid deficit incurred by the lactate

administration.

EVALUATION OF FETAL WELL-BEING

Measurement of the fetal heart rate and its changes

dur-ing labor is the primary means of intrapartum assessment of fetal

well-being. This may be done by intermittent aus-cultation with a stethoscope or

hand-held Doppler, or by the use of electronic fetal monitoring. The method

chosen may depend on risk assessment at admission, the prefer-ence of the

patient and the obstetric staff, and department policy. Risk factors include

vaginal bleeding, acute abdom-inal pain, temperature >100.4°F, preterm labor or rupture of

membranes, hypertension, and nonreassuring fetal heart rate pattern.

In the absence of risk factors on

admission, the standard approach to fetal monitoring is to determine, evaluate,

and record the fetal heart rate every 30 minutes in the active phase in the

first stage of labor, and at least every 15 minutes in the second stage. In the

presence of risk factors, fetal sur-veillance should be performed using either

intermittent aus-cultation or continuous fetal monitoring. During the active

first stage of labor, auscultation should be performed every 15 minutes,

preferably before, during, and after a contrac-tion, and continuous monitoring

should be evaluated at least every 15 minutes. During the second stage of

labor, the fetal heart rate should be monitored every 5 minutes using either

the intermittent or continuous procedure. If electronic fetal monitoring is

used, an external tocodynamometer is initially used to assess uterine activity,

providing information regard-ing the frequency and duration of contractions,

but not their intensity. Electronic fetal monitoring is not necessary for a

low-risk term pregnancy.

Control of Pain

Management of discomfort and pain

during labor is an essential part of good obstetric practice. Some patients

tolerate pain by using techniques learned in childbirth preparation programs.

It is important that bedside staff be knowledgeable about these pain management

techniques and be supportive of the patient’s decisions. Unless

con-traindicated, pharmacologic analgesics to ameliorate pain of contractions

should be made available on request to women in labor.

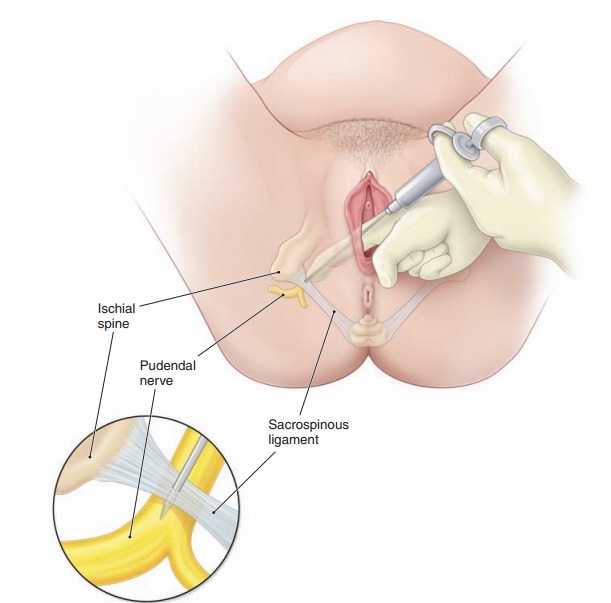

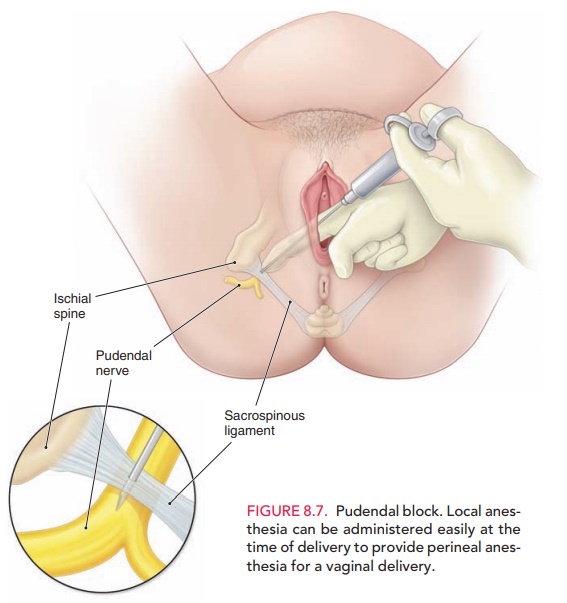

During the first stage of labor,

pain results from the contraction of the uterus and dilation of the cervix. This

pain travels along the visceral afferents, which accompany sympathetic nerves

entering the spinal cord at T-10, T-11, T-12, and L-1. As the fetal head

descends, there is also dis-tension of the lower birth canal and perineum. This

pain is transmitted along somatic afferents that comprise por-tions of the

pudendal nerves that enter the spinal cord at S-2, S-3, and S-4. To provide

relief from obstetric pain, the following methods of anesthesia and analgesia

are used.

· Epidural block: infusion

of local anesthetics or narcoticsthrough a catheter into the epidural space.

The most effective form of intrapartum pain relief in the United States, it can

be used in either vaginal or abdominal deliv-eries and in postpartum procedures

such as tubal ligation.

· Spinal anesthesia: a single

injection of anesthetic

· Combined spinal–epidural: combination

of the abovetwo techniques

· Local block: local

injection of anesthetic into theperineum or vagina. A pudendal block is a local block (Fig. 8.7).

· General anesthesia: inhaled

or intravenous administra-tion of anesthetic agents that results in a loss of

mater-nal consciousness. This technique is reserved only for cesarean

deliveries in selected cases.

To determine which method of

obstetric pain control should be used, the positive and negative aspects of

each should be considered. Of the regional modes of analgesia, epidural

anesthesia is superior to spinal anesthesia in that it can be left as a

continuous source of analgesia and anesthe-sia during both the labor and delivery

process. The advan-tage of this technique is its ability to provide analgesia

during labor as well as excellent anesthesia for delivery, yet main-tain the

patient’s sense of touch, facilitating participation in the birth process.

Spinal anesthesia provides good pain relief for procedures of limited duration,

such as cesarean delivery or vaginal delivery when labor is rapidly

progressing. Combined spinal–epidural anesthesia has advantages: the epidural

catheter to titrate medications throughout labor and the rapid onset associated

with spinal techniques. All of these types of regional anesthesia may be

associated with a postdural puncture headache. However, combined

spinal–epidural anesthesia avoids the risk of spinal headache in the mother and

reduces the risk of sympathetic blockade, which could lead to hypotension.

There is also less motor blockade than with spinal anesthesia. Local block may

pro-vide anesthesia for episiotomy and repair of vaginal and per-ineal

lacerations; however, paracervical block may result in fetal bradycardia.

General anesthesia is associated with complications such as maternal aspiration

and neonatal depression. If properly administered, it is effective for most

cesarean deliveries, but regional anesthesia is preferable.

Related Topics