Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Intrapartum Care

Management of Labor

Management of Labor

FIRST STAGE

Evaluation of the progress of labor is accomplished by means of a series of pelvic examinations. At the time of each vaginal examination, a sterile lubricant is used.

Each examination should identify cervical dilation,

effacement, station, position of the presenting part, and the status of the

membranes. These findings should be noted graphi-cally on the hospital record,

so that abnormalities of labor may be identified. During the latter portions of the first stageof labor, patients may

report the urge to push. This may indicatesignificant descent of the fetal

head with pressure on the per-ineum. More frequent vaginal examinations during

this time may be necessary. Similarly, if there are significant fetal heart

rate decelerations, more frequent examinations may be necessary to determine

whether the umbilical cord is pro-lapsed or if delivery is imminent.

In addition to rupturing the

membranes to insert an intrauterine pressure catheter or a fetal scalp monitor,

if needed, artificial rupture of

membranes many be bene-ficial in other ways. The presence or absence of meco-nium (fetal stool) can be identified.

However, rupture ofthe membranes does carry some risk, because the inci-dence

of infection may be increased if labor is prolonged, or umbilical cord prolapse

may occur if rupture of the membranes is undertaken before engagement of the

pre-senting fetal part. Spontaneous rupture of membranes has similar risks. The

fluid should be observed for meconium and blood. Fetal heart tones should be

assessed after mem-branes spontaneously rupture.

SECOND STAGE

Once the second stage of labor has been reached (i.e., com-plete cervical

dilation to 10 cm), voluntary maternal effort (pushing) can be added to the involuntary contractileforces of the

uterus to facilitate delivery of the fetus. With the onset of each contraction,

the mother is encouraged to inhale, hold her breath, and perform an extended

Valsalva maneuver. This increase in intra-abdominal pressure aids in fetal

descent through the birth canal.

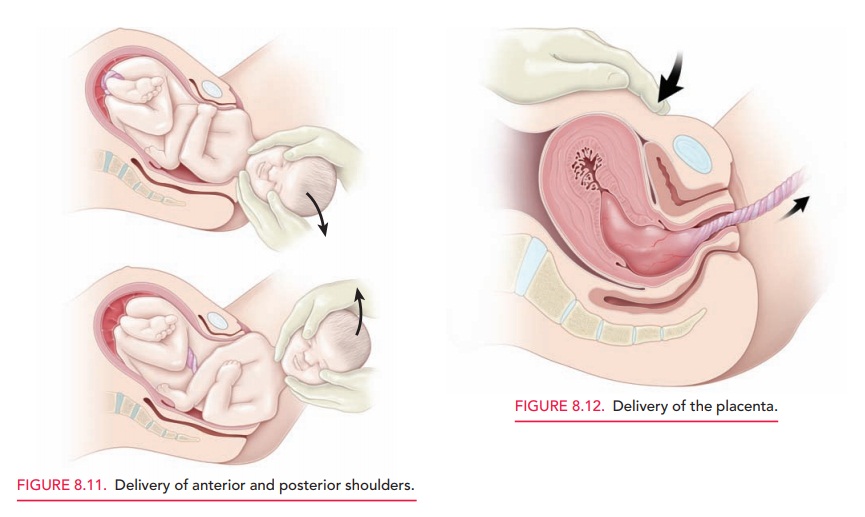

It is during the second stage of labor that the fetal head may undergo further alterations. Molding is an alteration in the relation of the fetal cranial bones, even resulting in par-tial bone overlap (Fig. 8.8). Some minor degree of molding is common as the fetal head adjusts to the bony pelvis. The greater the disparity between the fetal head and the bony pelvis, the greater the amount of molding. Caput succeda-neum is the edema of the fetal scalp caused by pressure onthe fetal head by the cervix. Molding and caput succedaneumare the two most common causes of overestimation of the amount of descent, that is, of station. When there is a large amount ofspace “between the back of the fetal head and the curve of the sacrum,” the physician is alerted to the possibility that the biparietal diameter of the fetal head is higher than might be thought based upon the physical level to which the presenting part’s farthest dimension has reached.

An extended second stage may last as

long as 2 to 3 hours, and the prolonged resistance encountered by the fetal

vertex may prevent appropriate identification of fontanels and sutures. Both

caput and molding resolve in the first few days of life. If identified before

the second stage of labor, these changes should be noted on the pelvic

examination and may indicate a potential problem in negotiation of the birth

canal.

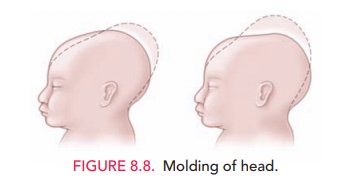

An episiotomy facilitates delivery by enlarging the vaginal outlet and

may be indicated in cases of instrumen-tal delivery and/or protracted or

arrested descent. With progressive labor and control of the fetal head and body

at delivery, the risk of obstetric laceration with a normal-sized infant is

low, so that the need for episiotomy is mini-mal. If an episiotomy is needed,

it should be performed only after the perineum has been thinned considerably by

the descending fetal head, and the incision should be somewhat longer on the

mucosal as compared to the perineal surface of the incision (Fig. 8.9).

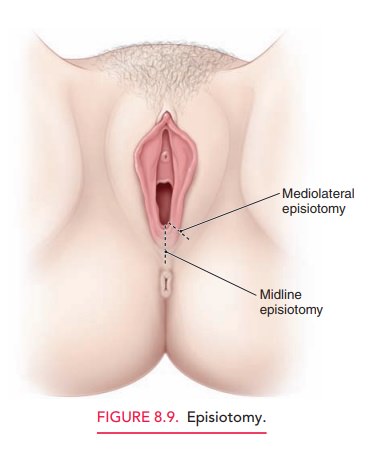

As the fetal head crowns (i.e., distends the vaginal opening), it is

delivered by extension to allow the smallest diameter of the fetal head to pass

over the perineum. This natural mechanism decreases the likelihood of

laceration or extension of an episiotomy. To support the perineal

This maneu-ver involves placing one hand over the vertex

while the other hand exerts pressure through the perineum onto the fetal chin.

A sterile towel is used to avoid contamination of this hand by contact with the

anus. The chin can then be delivered slowly, with control applied by both

hands.

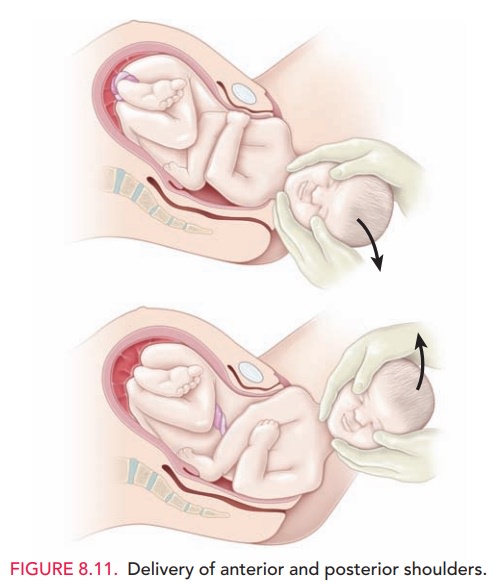

After delivery of the head, the

shoulders descend and rotate to a position in the anteroposterior diameter of

the pelvis. The attendant’s hands are placed on the chin and vertex, applying

gentle downward pressure, thus deliver-ing the anterior shoulder. To avoid

injury to the brachial plexus, care is taken not to put excessive force on the

neck. The posterior shoulder is then delivered by upward traction on the fetal

head (Fig. 8.11). Delivery of the body now occurs easily in most cases.

Immediately after delivery, the uterus significantly decreases in size.

Third Stage

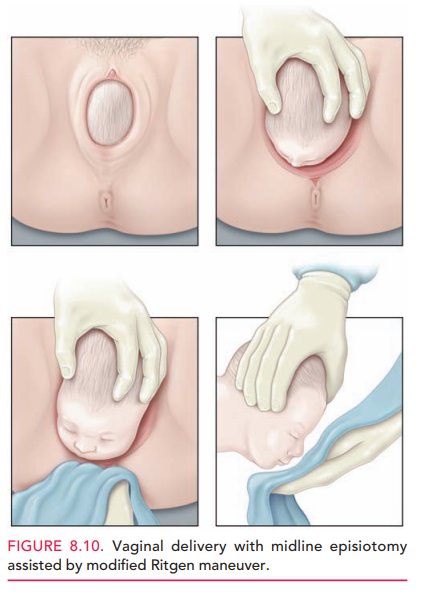

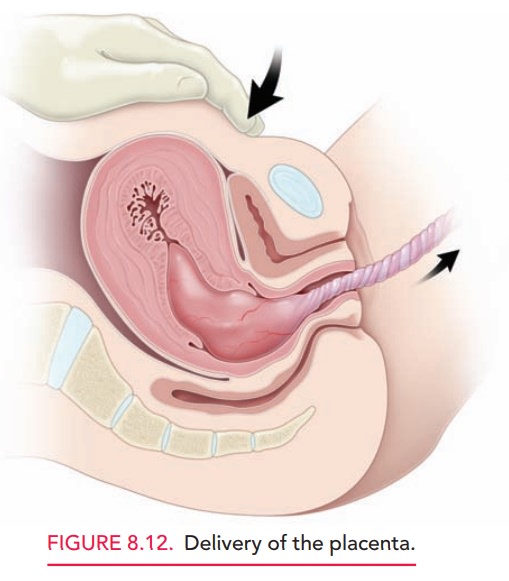

Delivery of the placenta is

imminent when the uterus rises in the abdomen, becoming globular in

configuration, indi-cating that the placenta has separated and has entered the

lower uterine segment; a gush of blood and/or “lengthen-ing” of the umbilical

cord also occur. These are the three classic signs of placental separation.

Pulling the placenta

Inappropriate application of force may

result in inversion of the uterus, an obstetric emergency associated with

profound blood loss and shock. Instead, it is appropri-ate to wait for spontaneous

extrusion of the placenta, some-times up to 30 minutes. As the placenta passes

into the lower uterine segment, gentle downward pressure is applied to the

fundus of the uterus, and the placenta is guided by very gen-tle traction on

the umbilical cord (Fig. 8.12). If necessary, the placenta may be removed

manually. This is accomplished by passing a hand into the uterine cavity and

using the side of the hand to develop a cleavage plane between the placenta and

the uterine wall. Anesthesia may be required. The umbilical cord should be

evaluated for the presence of the expected two umbilical arteries and one

umbilical vein.

After the

placenta has been removed, the uterus should be palpated to ensure that it has

reduced in size and become firmly contracted. Excessive

blood loss at this or any subsequent timeshould suggest the possibility of

uterine atony. The use of uterine massage as well as oxytocic agents such as

oxytocin, methylergonovine maleate (Methergine), or prostaglandins (carboprost

or misoprostol) may be used routinely in the circumstance of excessive

postpartum blood loss.

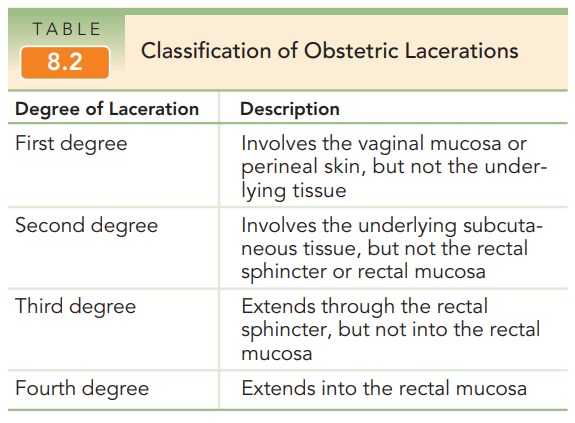

Inspection of the birth canal should be performed in a sys-tematic fashion. The introitus, vagina, perineum, and thevulvar area, including the periurethral area, should be evaluated for lacerations. Ring forceps are commonly used to hold and evaluate the cervix. Lacerations, if present, are most commonly found at the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions of the cervix. Repair is accomplished with an absorbable suture. Obstetric lacerations are clas-sified in Table 8.2.

Fourth Stage

For the first hour after delivery, the likelihood of serious post-partum complications is at its greatest. Postpartum uterine hem-orrhage occurs in approximately 1% of patients. It is more likely to occur in cases of rapid labor, protracted labor, uter-ine enlargement (large fetus, polyhydramnios, multiple ges-tation), or intrapartum chorioamnionitis. Immediately after the delivery of the placenta, the uterus is palpated to deter-mine that it is firm. Uterine palpation is done in this period to ascertain uterine tone. Perineal pads are applied and the amount of blood on these pads as well as pulse and blood pressure are monitored closely for the first several hours after delivery to identify excessive blood loss.

Related Topics