Chapter: Introduction to Human Nutrition: Measuring Food Intake

Methods for measuring intake on specified days

Methods for measuring intake on specified days

Menu records

Menu records are the simplest way of recording information on food intake. They only require the respondent to write down descriptions of the food and drink consumed at each meal and snack throughout the day for the specified days without quantifying the portions. A menu record is useful when information on food patterns rather than intake is required over a longer period or when respondents have difficulty in providing quantitative information. For example, elderly people may have difficulty in reading the divi-sions on household scales or in measuring out food portions. To derive information on nutrient intake from menu records investigators also need to obtain information on portion sizes of commonly eaten foods. Information on portion sizes may be derived from existing data or collected in a preliminary study.

Menu records work well when the diet is relatively consistent and does not contain a great variety of foods. The method can be used to distinguish differ-ences in the frequency of use of specific foods over time, to determine whether quantitative short-term intake records are likely to be representative of habit-ual intake and as a way of assessing compliance with special diets.

Weighed records

Weighed records require the respondent, or a field-worker, to weigh each item of food or drink at the time it is consumed and to write down a description of this item and its weight in a booklet specially designed for this purpose (sometimes referred to as a food diary). Weighed records are usually kept for 3, 4, 5, or 7 consecutive days. To obtain accurate informa-tion it is necessary to use trained fieldworkers to collect the data or to demonstrate the procedures and to provide clear instructions to the respondents not only on how to weigh foods but also on how to describe and record foods and recipes. When respon-dents are responsible for weighing, the investigator needs to make regular visits to the respondent during the recording period to ensure that the equipment is being used correctly and that information is recorded accurately and in sufficient detail.

Weighing can be carried out in two different ways:

1 The ingredients used in the preparation of each meal or snack, as well as the individual portions of prepared food, must be weighed. Any food waste occurring during preparation and serving or food not consumed is also weighed.

2 All food and beverage items are weighed, in the form in which they are consumed, immediately before they are eaten, and any previously weighed food that is not consumed is also weighed.

The first approach is sometimes referred to as the precise weighing technique and is usually carried out by trained fieldworkers rather than the respondents themselves. It is thus very labor intensive, time-consuming, and expensive to carry out. It is most appropriate when the food composition tables avail-able contain few data on cooked and mixed dishes or if exposure to contaminants is being assessed. It should be noted, however, that the precise weighing technique does not allow for nutrient losses in cooking. To take these into account information on cooking losses for the most commonly used cooking methods must also be available.

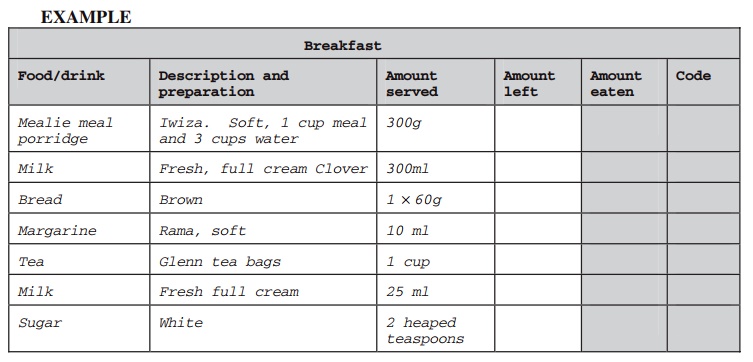

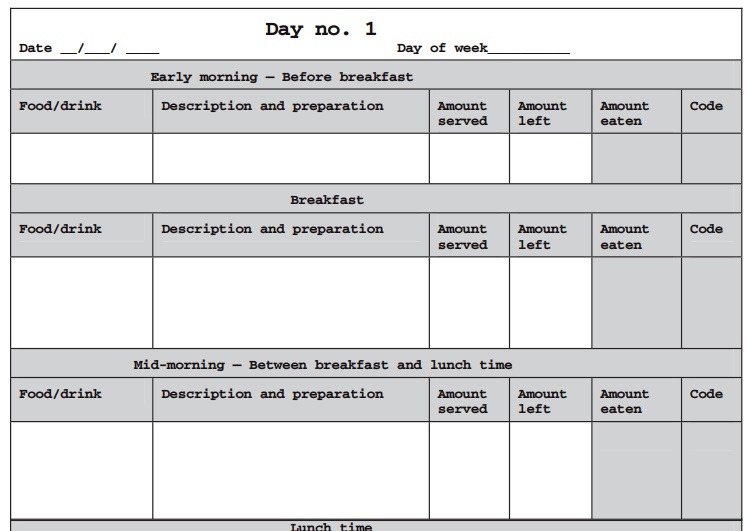

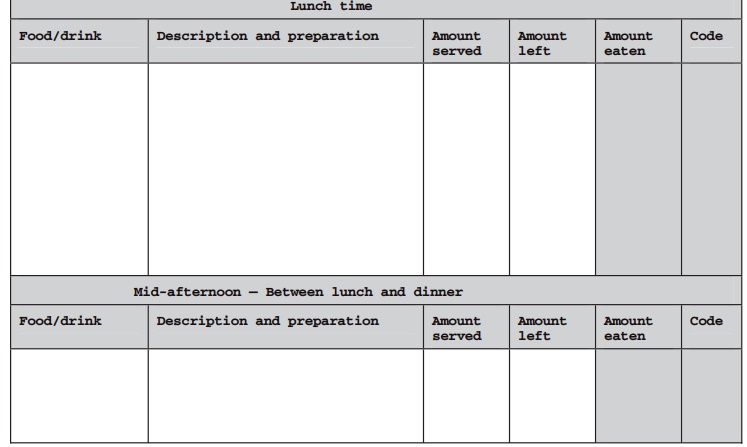

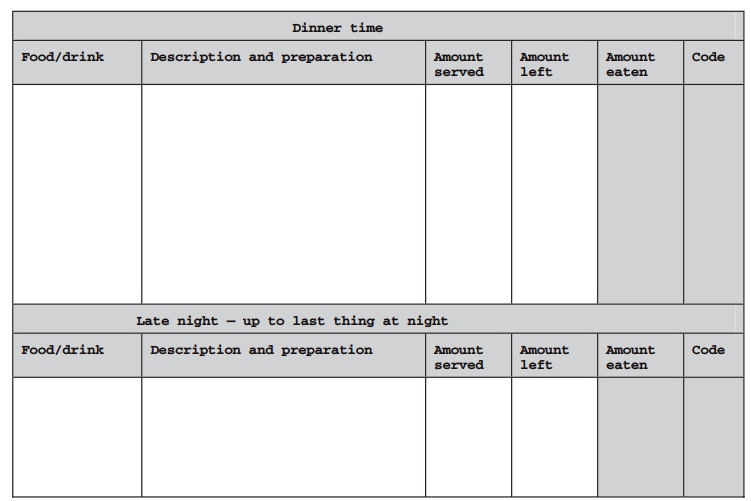

The second procedure, which is more widely used, involves weighing all food eaten in the form in which it is consumed. It is sometimes referred to as the weighed inventory method. Using this method the nutrient content of the diet can be determined either by chemical analysis of duplicate portions of indi-vidual foods or aliquots of the total food consumed or, most often, from tables of food composition. Scales used for weighing food need to be robust and able to weigh up to 2 kg, accurate to at most 5 g and preferably to 1–2 g. Digital scales are preferred as these are more accurate and easier to read than spring-balance scales. Record books must have clear instruc-tions, be easy to use, and of a convenient size. They should contain guidelines for weighing and examples illustrating the level of detail required. Figure 10.3 shows an extract from the instructions and record

Seven day food diary instructions

1. Please use this booklet to write down everything you eat or drink for the following seven days.

As you will see, each day is marked into sections, beginning with first thing in the morning and ending with bedtime. For each part of the day write down everything that you eat or drink, how much you eat or drink, and a description if necessary. If you do not eat or drink anything during that part of the day, draw a line through the section.

2. You have been provided with: a scale to weigh food, a measuring jug to measure liquids, and a set of measuring spoons to measure small amounts of foods and liquids.

3. Write down everything at the time you eat or drink it. Do not try to remember what you have eaten at the end of the day.

4. Before eating or drinking, the prepared food or drink must be weighed or measured and written in the record book. If you do not consume all the food or drink, what is left must also be weighed or measured and recorded in the book.

5. Please prepare foods and drinks as you always do. Also eat and drink in the same way as normal: eat the foods and drink in the amounts and at the times that you always eat and drink. Try not to change the way you eat and drink at all.

6. We need to know ALL the food and drink you take during these 7 days. So if you eat away from home (e.g., at work, with friends, at a cafe or restaurant) please take your measuring equipment with you so you can still measure your food. Also do not forget to measure food bought at take-aways.

7. Please write down the recipes of homemade dishes such as stews, soups, cakes, biscuits, or puddings. Also say how many people can eat from them or how many biscuits or cakes you get from the recipe.

8. On the next page is a list of popular foods and drinks. Next to each item is the sort of thing we need to know so that we can tell how it is made and how much you had. This list does not contain all foods, so if a food that you have eaten is missing, try to find a food that is similar to it. Please tell us as much about the food as you can.

9. Please tell us the amount and type of oil or fat that you use for cooking, frying, or baking.

10. Most packet and tinned foods, like Simba chips, Niknaks, corned meat, tinned pilchards, have weights printed on them. Tins, bottles, and boxes of cold drinks and alcoholic drinks also have weights printed on them. Please use these to show us how much you ate or drank. When possible, please keep the empty packets, bottles, or tins.

Please note: we need to know the amount you eat or drink. So, if you do not eat the whole packet or tin of food, or drink the whole bottle of cold drink, please measure the amount you eat or drink.

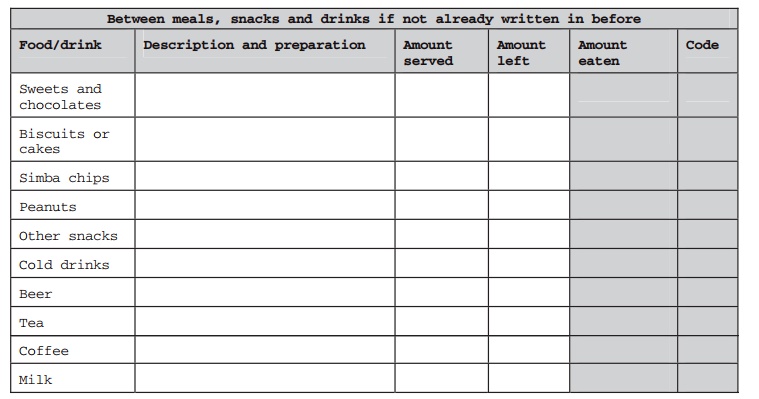

11. At the end of each day there is a list of snacks and drinks that can easily be forgotten. Please write any extra items in here if you have not already written them down in some part of the day.

12. The research assistant will visit you during the record days to help you if you have any questions or problems. She will collect the equipment and record book after the 7 days.

All the information you give us is strictly confidential. It will only be used for research purposes. Only your subject number appears on the record book. Nobody will be able to identify you from the record book.

The strengths of the weighed record are that it pro-vides the most accurate measurement of portion sizes, as food is recorded as it is consumed, it does not rely on memory, and it gives an indication of food habits such as the number and times of meals and snacks. Weighed records kept for 3 or more days and including a weekend day are usually considered to represent habitual intake.

Limitations are that weighed records are time-con-suming and require a high level of motivation and commitment from both the investigator/fieldworkers and respondents. Respondents may change their food habits to simplify measuring and recording or may not measure and record food items accurately. Samples of respondents who keep weighed records may not be representative of the population for three reasons:

1 because of the high respondent burden, respon-dents must be volunteers and thus random sampling cannot be used

2 respondents are limited to those who are literate and who are willing to participate

3 those who volunteer may have a specific interest in food intake, e.g., being very health conscious, and thus may not be representative of the population.

Metabolic studies carried out to determine absorp-tion and retention of specific nutrients from mea-surements of intake and excretion are a specialized application of the weighed food intake record. In metabolic studies all foods consumed by the respon-dents are usually either preweighed or weighed by the investigators at the time of consumption. The foods consumed are usually also analyzed for the nutrient constituents of interest or prepared from previously analyzed ingredients.

Estimated records

This method of recording food intake is essentially similar to weighed records except that the amounts of food and beverages consumed are assessed by volume rather than by weight, i.e., they are described in terms of cups, teaspoons, or other commonly used house-hold measures, dimensions, or units. Food photo-graphs, models, or household utensils may be used to assist quantification. These descriptive terms have then to be converted to weights by the investigator, using appropriate conversion data when available, or by obtaining the necessary information when not. For example, the investigator can determine the volume of the measures commonly used in a given household and then convert these to weights by weighing food portions of appropriate size or using information about the density (g/ml) of different kinds of foods. A record book for this kind of study is similar to that for a weighed record study. In some situations a precoded record form that lists the commonly eaten foods in terms of typical portion sizes may be appropriate, but an open record form is generally preferred.

Since there is no need for weighing scales to be provided the record forms can be distributed by mail rather than by interviewers. This is convenient if a large number of respondents located over a large geo-graphical area is involved. In this situation the follow-up interview, after completion of the record, could be conducted by telephone. In situations in which respondents may not be familiar with measuring foods, the investigator needs to train and provide clear instructions to the respondents and to check that respondents are performing measurements and recording correctly during the record period.

The strengths and limitations of estimated records are similar to those of the weighed record, but the method has a lower respondent burden and thus a higher degree of cooperation. Loss of accuracy may occur during the conversion of household measures to weights, especially if the investigator is not familiar with the utensils used in the household.

Weighed records are used in countries where kitchen scales are a common household item and quantities in recipes are given by weight, e.g., the UK. Estimated records are favored in countries where it is customary for recipe books to give quantities by stan-dard spoons and cups, e.g., the USA and Canada. The dietary literature frequently uses the phrase “diet record” without specifying how portions were quanti-fied. In these instances, estimated records are most likely to have been used.

Recalled intake

Information on dietary intake over a specified period can also be obtained by asking individuals to recollect the types and amounts of food they have eaten. This approach therefore does not influence the type of food actually consumed in the way that a food record may do. However, it is open to misrepresentation of the dietary pattern, with respondents either reporting a “good” dietary pattern in order to project a good self-image or reporting a “poor” dietary pattern in the hope of receiving hand-outs or other assistance. Response rates in short-term recall studies tend to range from 65% to 95% and depend largely on how, under what conditions, and from whom the infor-mation is obtained. A recall may consist of a face-to-face or telephone interview or of a self-completed questionnaire.

The 24 hour recall is probably the most widely used method of obtaining information on food intake from individuals. It is often used in national surveys because it has a relatively high response rate and can provide the detailed information required by regula-tory authorities for representative samples of differ-ent population subgroups.

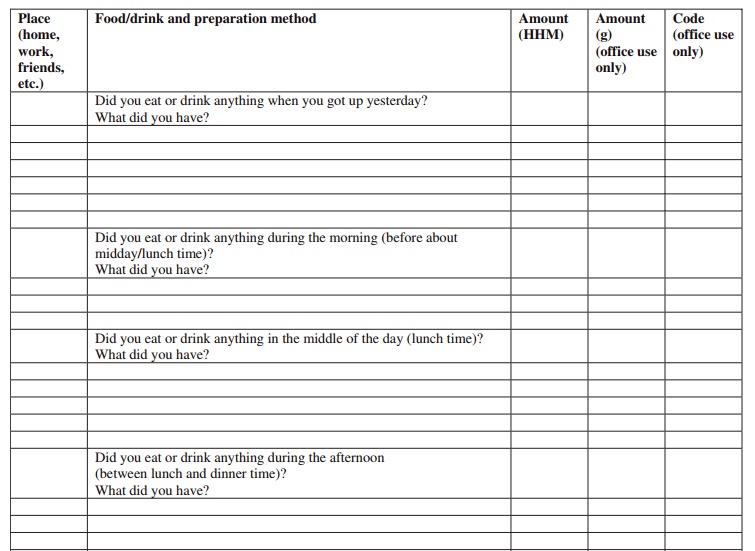

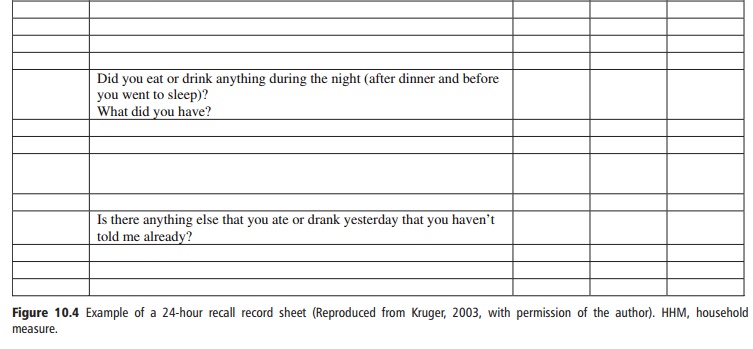

The 24 hour recall is an attempt to reconstruct quantitatively the amount of food consumed either in the previous 24 hours or on the previous day. This period is considered to provide the most reliable recall of information. With longer periods memory becomes an increasing limitation. Incomplete recalls are more likely with self-completed records unless these records are subsequently checked with the respondent by the investigator. An example of a 24 hour recall sheet is shown in Figure 10.4.

Traditionally, the food intake has been reviewed chronologically, i.e., starting from the time the respon-dent wakes up and going through the day until the following morning. Recalling daily activities often assists the respondent to remember food intakes.

Problems encountered in estimating the amounts of foods consumed are similar to those encountered with estimated records. Recalls conducted by means of a face-to-face interview often use aids such as pho-tographs, food models, and household utensils to help the respondent to describe how much food was eaten. In telephone recalls respondents may be pro-vided with pictures or other two-dimensional aids prior to the interview to help them to describe the amounts consumed. There is, however, very little information on how effective these aids are. For this type of study a standardized interview protocol, which is based on a thorough knowledge of local food habits and commonly used foods, is essential when more than one interviewer is involved.

In its simplest form, the 24 hour recall consists of foods and the amounts consumed over a 24 hour period. In order to obtain sufficient information to quantitatively analyze food intakes from a 24 hour recall, a skilled interviewer will use several “passes” or stages in questioning the respondent. This procedure has become known as the multiple-pass 24 hour recall. This is an interviewing technique consisting of three to five steps which take the respondent through the previous day’s food consumption at different levels of detail. All multiple-pass 24 hour recalls com-mence with the respondent simply listing all foods and beverages consumed during the previous 24 hours. The content and number of further steps differ from study to study. The US Department of Agricul-ture (USDA) has developed a five-step multiple pass method comprising the following passes (steps) (Conway et al., 2003).

Pass 1 Quick list: the respondent lists all food and beverages consumed during the preceding 24 hours in any order without any prompting or interrup-tions from the interviewer.

Pass 2 Forgotten foods list: the interviewer asks about categories of foods, such as snacks and sweets, which are frequently forgotten.

Pass 3 Time and occasion: the interviewer asks for details of the times and names of the eating occa-sions at which foods were consumed.

Pass 4 Detail: the interviewer asks for details, such as descriptions and preparation methods, and amounts of foods consumed.

Pass 5 Review: the interviewer goes through the information probing for any foods which may have been omitted.

A simplified version of the multiple-pass 24 hour recall consists of three steps:

Pass 1 the respondents provide a list of all foods eaten on the previous day using any recall strategy they desire, not necessarily chronological.

Pass 2 the interviewer obtains more detailed infor-mation by probing for amounts consumed, descrip-tions of mixed dishes and preparation methods, additions to foods such as cream in coffee, and giving respondents an opportunity to recall food items that were initially forgotten.

Pass 3 in a third pass the interviewer reviews the list of foods to stimulate reports of more foods and eating occasions.

The multiple-pass approach is thought to assist recall more effectively than chronological cues and thus provide more accurate and complete information. This approach, however, is more time-consuming than the traditional 24 hour recall and may irritate respondents by seemingly asking about the food intake over and over again. Irrespective of the approach used, it is essential that all interviewers are thoroughly trained, that the approach is tested in the target population prior to the study, and that the same procedure is used by all interviewers with all respon-dents throughout the study.

A major drawback of the 24 hour recall is that it provides information for only a single day and there-fore does not take account of day-to-day variation in the diet. In large cross-sectional studies in which the aim is to determine average intakes of a group of individuals, a single 24 hour recall may be sufficient. When the diets of individuals are assessed or when sample sizes are small, repeated 24 hour recalls are required. This method is known as multiple 24 hour recalls. The number of recalls depends on the aim of the study, the nutrients of interest, and the degree of precision needed. For example, when diets consist of a limited variety of foods two 24 hour recalls may be sufficient whereas four or more recalls may be required when diets are complex. Recalls may also be repeated during different seasons to take account of seasonal variations. (Note that mul-tiple 24 hour recalls must not be confused with the multiple-pass 24 hour recall technique. The multiple-pass 24 hour recall refers to an interviewing tech-nique, whereas the multiple 24 hour recall method refers to repeated 24 hour recalls conducted per respondent.)

The strengths of the 24 hour recall method are that it has a low respondent burden in comparison with food records and thus compliance is high, it does not require respondents to be literate, it does not alter usual food intake, and it is relatively quick and inex-pensive to administer and therefore is cost-effective when large numbers of respondents are involved. It is most successful in populations with limited dietary variety and when respondents are able to accurately recall and express the types and amounts of foods consumed and when interviewers are skilled in the interview technique.

As already stated a major drawback of the 24 hour recall is that it does not give an accurate reflection of habitual dietary intake if only a single 24 hour recall is conducted. This may be overcome to some extent by conducting repeated 24 hour recalls. Another dif-ficulty is that the 24 hour recall relies on the respon-dent to accurately recall and report the types and amounts of foods consumed. There is a tendency for respondents to overestimate low intakes and under-estimate high intakes. This is known as the flat slope syndrome. Respondents may omit certain foods that are considered “bad” or include foods not consumed but considered “good” (phantom foods) in order to impress the interviewer.

Of the methods so far described weighed records should contain the least error as they report all food consumed on specified days with weighed portions. Estimating the size of portions increases error and, if menu records are quantified with average portions, then the error at the individual level is further increased. If food that has already been eaten has to be recalled then poor memory can introduce an addi-tional source of error. All methods that report intake on specified days are also subject, in individuals, to the error associated with day-to-day variation in intake, but this error can be reduced by increasing the number of days studied.

Related Topics