Chapter: Introduction to Human Nutrition: Measuring Food Intake

Indirect measurement of food intake

Indirect measurement of food intake

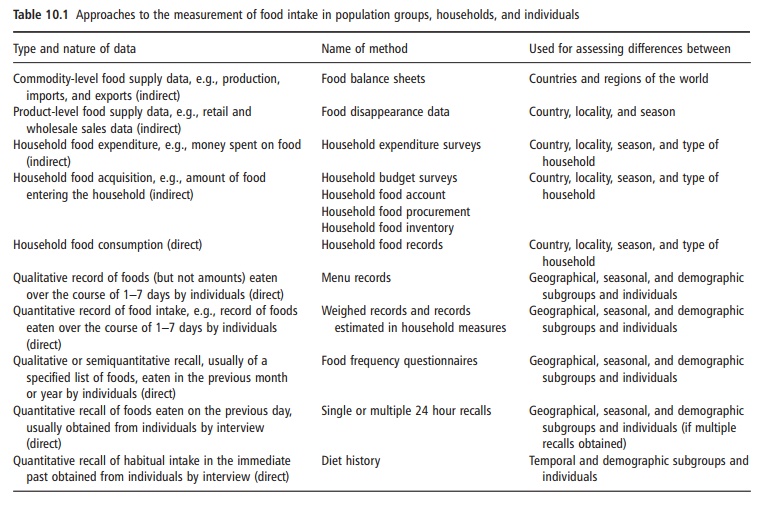

Indirect measurements of food intake make use of information on the availability of food at national, regional, or household levels to estimate food intakes, rather than using information obtained directly from individuals who consume the food. Indirect methods are most useful at the population and household levels for determining the amount and types of foods:

● available for consumption at national level (commodity-level food supply data)

● traded at wholesale or retail levels (product-level food supply data)

● purchased at household level (household-based budget/expenditure data).

Commodity level food supply data

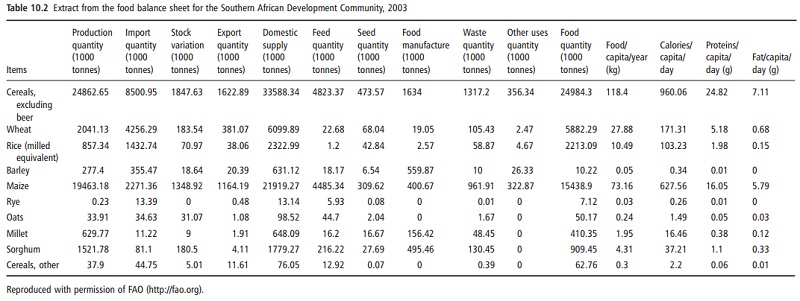

Food supply data are usually produced at national level from compilations of data from multiple sources. The primary sources of data are records of agricul-tural production and food exports and imports adjusted for changes in stocks and for agricultural and industrial use of food crops and food products. National food supply data are usually referred to as “food balance sheets” or as “apparent consumption data.” Food balance sheets give the total production and utilization of reported food items and show the sources (production, stocks, and imports) and utiliza-tion (exports, industrial use, wastage, and human consumption) of food items available for human con-sumption in a country for a given reference period. The amount of each food item is usually expressed per caput (per person) in grams or kilograms per year by dividing the total amount of food available for human consumption by relevant population statis-tics. An analysis of the energy, protein, and fat pro-vided by the food item may also be given.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has compiled and published food balance sheet data for most countries in the world since 1949. Regularly updated food balance sheet data are available online at www.fao.org for most countries for about 100 primary crop, livestock, and fishery commodities and some products such as sugar, oils, and fats derived from them. Table 10.2 shows an extract from the food balance sheet for the Southern African Development Community for 2003.

The accuracy of food balance sheets and apparent consumption data depends on the reliability of the basic statistics used to derive them, i.e., population, supply, utilization, and food composition data. These can vary markedly between countries not only in terms of coverage but also in terms of accuracy.

Several internal and external consistency checks are built into the preparation of the FAO food balance sheets, but users still need to evaluate the data for themselves in the context of the purpose for which they are being used. One of the crucial factors in using the data appropriately is to understand the terminol-ogy used.

Food balance sheets provide important data on food supply and availability in a country and show whether the food supply of the country as a whole is adequate for the nutritional needs of its population.

Over a period of years, food balance sheets show trends in national food supply and food consumption patterns. They may be used for population compari-sons such as comparing population estimates of fat intake with cardiovascular disease rates.

In practice, the data needed to compile food balance sheets are not always available and imputations or estimates may have to be used at each stage in the calculation of per caput food and nutrient availability. In most industrialized countries reliable data are usually available on primary commodities, but this is not necessarily the case for the major processed products. For example, data may be available on flour but not on products such as bread and other cereal products made from flour that may have quite differ-ent nutrient characteristics. The overall impact of incomplete data will vary from country to country, but it has been suggested that in general underestima-tion of per caput availability of nutrients is more likely in less developed countries and overestimation in countries where most of the food supply is con-sumed in the form of processed products.

It is also very important to keep in mind that food balance sheets show only data on foods available for consumption, not the actual consumption of foods; nor do they show the distribution of foods within the population, for example among different regions or among different socioeconomic, age, and gender groups within the population. Food balance sheets also do not provide information on seasonal varia-tions in food supply.

Product-level food supply data

In some countries (e.g., Canada and the USA) data on per caput food availability are prepared from information on raw and processed foods available at the retail or wholesale level. Such data are derived mainly from food industry organizations and firms engaged in food production and marketing such supermarkets. Errors arise mainly from inappropriate conversion factors for processing, the absence of data for some processed products, and the lack of data on food obtained from noncommercial sources such as home gardens, fishing, and hunting.

Commercial databases such as those produced by the AC Neilsen Company and the electronic stock-control records from individual supermarkets, from which they are compiled, have the potential for moni-toring national-, regional-, and local-level trends in the food supply, at a product-specific level. Their principal disadvantage at present lies in the costs associated with processing or otherwise accessing, on a regular basis, the very large amounts of data that are involved.

FAO food balance sheets and similar sources of information are primarily useful for formulating agricultural and health policy, for monitoring changes in national food supplies over time, and as a basis for forecasting food consumption patterns. They can also be used to make intercountry comparisons of food and nutrient supplies, provided that potential differ-ences in data coverage and accuracy are taken into account.

Household-based surveys

Household-based surveys determine the foods and beverages available for consumption at family, house-hold, or institutional levels. Some surveys such as household expenditure or household budget surveys determine the amount of money spent on food for a given period, while others, such as the food account, food inventory, and food record methods, attempt to describe the food available and/or consumed by a household or institution.

Household food expenditure surveys

Household food expenditure surveys determine the amount of money spent on food by a household over a given period. Household food expenditure data can provide useful information for nutritionists on food expenditure patterns of different types of households, but without quantitative information this cannot be translated into nutrient patterns.

Household budget surveys (HBSs) are conducted at regular intervals in many European countries and many also collect data on food quantities as well as cost. HBSs have several advantages:

●they are usually conducted at regular intervals of between 1 and 5 years

●they are conducted on representative samples of households

●the food supply information collected can be classified by sociodemographic characteristics, geographical location, and season.

The large amount of nutrition-related information collected by these surveys offers the potential to assess the nutritional patterns of different population groups, to identify high-risk groups for nutrition-related conditions, to monitor trends in food patterns over time, and for developing nutrition policy. A modification of the HBS, known as the list recall method, includes quantities of items purchased, which strengthens the information. The information available from HBSs, however, also needs to be con-sidered in the context of their limitations.

● Information provided by HBSs differs from country to country both in the number of food items recorded and in the type of information collected.

● Most surveys do not include expenditure informa-tion on food consumed outside the home.

● Most surveys do not collect information on foods acquired by means other than purchase. For example, food obtained as gifts, produced by the household itself, or harvested from the wild.

● Most surveys do not collect information on domes-tic wastage, i.e., food given to pets, spoiled food and plate waste, or food provided for guests.

● It is often difficult to estimate the nutrient content of the food available to the household because data are reported only at food group and not individual food level.

● Differences in food coding systems between coun-tries make it difficult to compare data between countries.

Three conclusions emerge from this list. First, the data obtained from HBSs are not necessarily compa-rable between countries. Second, most HBSs do not collect all of the information needed to provide an accurate assessment of the total food supply available at household level. Third, provided that the HBS methodology remains consistent, HBSs can provide a great deal of valuable information about food pat-terns over time, in different sociodemographic groups, and in different parts of the country, and how these relate to social, economic, and technological changes in the food supply.

Household food account method

In the food account method, the household member responsible for the household’s food keeps a record of the types and amounts of all food entering the household including purchases, gifts, foods produced by the household itself such as from vegetable and fruit gardens, foods obtained from the wild, or from other sources. Amounts are usually recorded in retail units (if applicable) or in household measures. Information may also be collected on brand names and costs. The recording period is usually 1 week but may be as long as 4 weeks.

This method is used to obtain food selection pat-terns from populations or subgroups within a popu-lation. It has the advantage of being fairly cost-effective and is particularly useful for collecting data from large samples. It may also be repeated at different times of the year to identify seasonal variations in food procurement.

The food account method does not measure food consumption, wastage, or other uses, nor does it account for foods consumed outside the home. It assumes that household food stocks stay constant throughout the recording period, which may not nec-essarily be the case. For example, food purchases may be done once a month and therefore stocks may be depleted in the days preceding the purchase. It also does not reflect the distribution of food within the household and therefore cannot be used to determine food consumption by individuals within the house-hold. Since the method relies on the respondents being literate and cooperative, bias may be introduced in populations with high levels of illiteracy. The fact of having to record the acquisition may lead to respondents changing their procurement patterns either to simplify recording or to impress the investigator.

Household food procurement questionnaire/interview

A food procurement questionnaire or interview may be used as an alternative method to the food account method. In this method, the respondent indicates, from a list of foods, which are used, where these are obtained, the frequency of purchase, and the quanti-ties acquired for a given period. The uses of the food procurement method are similar to those of the food account: to describe food acquisition patterns of populations or subpopulations. In contrast to the food account method, it does not require the respon-dent to be literate as it may be administered as an interview and it does not influence purchasing or other procurement patterns.

The food procurement questionnaire/interview does not provide information on actual food con-sumption or distribution within the household. As the method relies on recalled information, errors may be introduced by inaccurate memory or expression of answers.

Household food inventory method

The food inventory method uses direct observation to describe all foods in the household on the day of the survey. The investigator records the types and amounts of foods present in a household, whether raw, processed, or cooked, at the time of the study. Information may also be collected on how and where food is stored.

A food inventory may be combined with the food account to determine the changes of food stocks during the survey period. It may also be used together with a food procurement questionnaire to describe the acquisition of foods in the household. This method is time-consuming for the investigator and very intrusive for the respondent, but is useful when foods are procured by means other than purchase and when levels of food security in vulnerable households need to be assessed.

Household food record

All foods available for consumption by the household are weighed or estimated by household measures prior to serving. Detailed information such as brand names, ingredients, and preparation methods are also recorded over a specific period, usually 1 week. This method provides detailed information on the food consumption patterns of the household, but it is very time-consuming and intrusive and relies heavily on the cooperation of the household. As for the other household methods, it does not provide information on distribution of food within the house-hold or on individual consumption. When details of the household composition are given, estimates of individual intakes may be calculated. The method also does not determine foods eaten away from the home nor does it take into account food eaten by guests to the home.

Related Topics