Chapter: Modern Medical Toxicology: Neurotoxic Poisons: Inebriants

Methanol - Inebriant Neurotoxic Poisons

Methanol

Synonyms

Methyl

alcohol; Methyl hydroxide; Monohydroxymethane; Colonial spirit; Columbian

spirit; Pyroxylic spirit; Wood alcohol; Wood naphtha; Wood spirit

Physical Appearance

Methanol

is the simplest of the primary alcohols and is a colourless, highly polar,

flammable liquid. Pure methanol has a faintly sweet odour at ambient tempera-

tures; crude methanol may have a repulsive, pungent odour. It has a bitter

taste.

Uses and Sources

·

Antifreeze (10 to 50%)

·

Carburettor cleaner (20%)

·

Denatured spirit (5 to 10%): While denatured spirit most

often is a mixture of ethanol (90 to 95%) with methanol (5 to 10%),

occasionally other substances may be used instead of the latter, e.g. acetone,

aniline dyes, benzene, cadmium, camphor, castor oil, diethyl phthalate, ether,

petrol, isopro-panol, kerosene, nicotine, pyridine bases, sulfuric acid, or

terpineol.

·

Embalming fluid (20%)

·

Leather dyes (30%)

·

Paint remover

·

Varnish and shellac (5%)

·

Windshield washing fluid (35 to 95%).

Usual Fatal Dose

·

About 70 to 100 ml (range: 15 to 250

ml).

·

Serious toxicity may occur from

ingestion of 0.25 ml/kg of 100% methanol, and fatalities might occur from

ingestion of 0.5 ml/kg of 100% methanol.

Mode of Action

■■ Methanol is rapidly

absorbed through the skin, respira-tory tract and gastrointestinal tract. Peak

plasma levels are usually reached within 30 to 60 minutes following inges-tion,

although a long latent period (roughly 18 to 24 hours) usually is seen before

toxic symptoms develop.

■■ In the liver,

methanol is metabolised to formaldehyde (by alcohol dehydrogenase) and then to

formic acid (by aldehyde dehydrogenase) which is responsible for retinal

toxicity as well as metabolic acidosis.

■■ There are two pathways

for metabolism of formic acid, oxidation via the catalase-peroxidase system, or

metabo-lism by the tetrahydrofolic acid-dependant one-carbon pool which is

catalysed by 10 -formyl-tetrahydrofolate synthetase. Since metabolism is slow,

significant levels of methanol can be found in the body for up to seven days

after ingestion.

Clinical Features

· Symptoms may be delayed for 12 to 24

hours (Range: 1 to 72 hours). The earliest manifestations include vertigo,

headache with stiff neck (meningismus),

nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.

·

Later there is ocular toxicity characterised by blurred or

dimmed vision (“flashes” or “snowstorm”), and photo-phobia. Constricted visual

fields, spots before the eyes, sharply reduced visual acuity, optic atrophy,

blindness, and nystagmus have all been described. Ophthalmologic exami-nation

usually reveals dilated pupils with sluggish light reaction. Fixed dilated

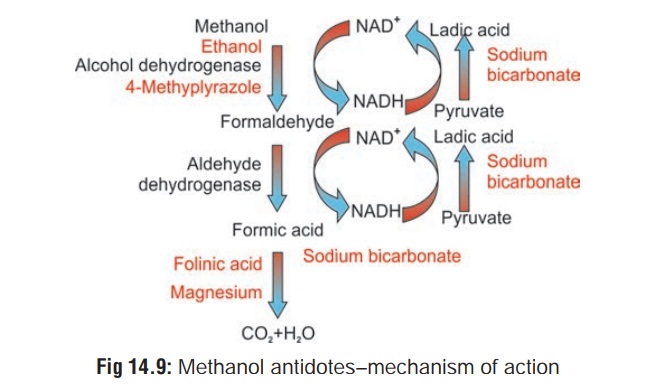

pupils suggest severe poisoning. Fundoscopy (Fig 14.8) reveals hyperaemia of optic disc followed by retinal

oedema. Irreversible sequelae include optic atrophy and visual field

impairment.

· Metabolic acidosis (high anion gap)

is usually severe. A pH of less than 7.0 and bicarbonate less than 10 mEq/L are

not uncommon following significant intoxication. The onset of acidosis may be

delayed up to 18 to 48 hours, especially if ethanol has also been ingested.

Therefore, the absence of acidosis does not rule out a significant methanol

ingestion.

· Other features include tachycardia,

hypotension, and hypo-thermia. Convulsions are a late feature and may be

followed by coma.

· Hypomagnesaemia, hypokalaemia, and

hypophosphataemia have been reported.

· Occasionally a patient develops

transient Fanconi syndrome (hypouricaemia, hypophosphataemia, glycosuria, and

hyperchloraemic metabolic acidosis).

· Acute necrotising pancreatitis may

result from severe methanol poisoning.

· Cause of death is usually

respiratory failure, which may precede the cessation of heart beat by several

minutes. In fatal methanol poisoning cases, marked sinus bradycardia may

develop with widening of the pulse pressure. Further, severe hypotension,

requiring fluid and vasopressor therapy, occurs terminally in severe methanol

intoxications.

· The most common permanent sequelae following recovery from severe poisoning are optic neuropathy, blindness, Parkinsonism, toxic encephalopathy, and polyneuropathy.

·

Permanent ocular abnormalities may include pallor of the optic disc,

attenuation and sheathing of retinal arterioles, a diminished pupillary light

reaction, reduced visual acuity, central scotomata, and defects of optic nerve

fibre bundles.![]()

Diagnosis

·

Obtain CBC, electrolytes,

urinalysis, and arterial blood gases in symptomatic patients or those with a

history of significant exposure. Measure serum pH and electrolytes.

·

High anion gap acidosis.

·

Elevated osmolal gap.

·

Hypophosphataemia.

·

Elevated creatine phosphokinase.

·

Elevated amylase.

·

Blood methanol level: more than 50

mg/100 ml indicates serious poisoning. A detectable formic acid level may be

consistent with methanol poisoning, as methanol is metabo-lised to formic acid.

·

CT Scan/MRI—Symmetrical areas of

necrosis in the putamen of the brain are a classic finding in cases of acute

lethal methanol toxicity. However, these findings are also present in other

conditions, such as Wilson’s disease and Leigh’s disease, and are not

pathognomonic for methanol poisoning.

Treatment

·

Patients with abnormal vital signs, visual disturbances,

pulmo-nary oedema, evidence of renal dysfunction, high methanol levels,

significant acidosis, or coma should be admitted to an intensive care unit.

· Stomach wash with sodium

bicarbonate.

· Ipecac-induced emesis is not

recommended because of the potential for CNS depression.

· Activated charcoal does not adsorb

significant amounts of methanol. Its use in the face of ingestion may be

indicated to prevent absorption of co-ingested substances.

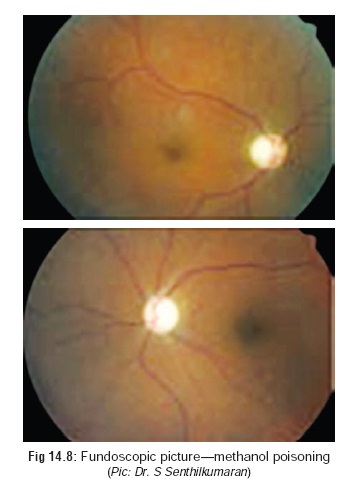

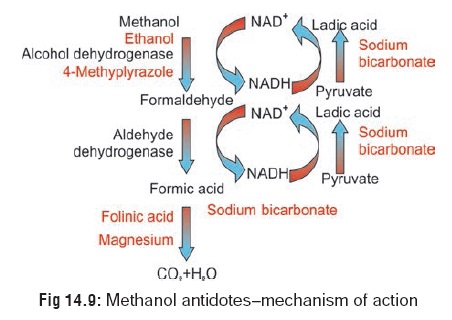

Antidotes (Fig 14.9):

· Ethanol is the specific antidote since it preferentiallycompetes for the same enzyme (alcohol dehydrogenase) and prevents the metabolism of methanol which is then excreted unchanged in the urine. Ethanol has about 20 times the affinity for alcohol dehydrogenase compared to methanol.

This competitive effect of ethanol gains more time for excretion of unchanged methanol from the body, and it also inhibits the formation of methanol metabolites that produce severe acidosis. Formic acid is metabolised to carbon dioxide and water via a folate dependant system.

–– Mode of administration:

--10% ethanol at a dose of 10 ml/kg

administered IV over 30 minutes, followed by 1.5 ml/kg/hr, so as to produce and

maintain a blood ethanol level of 100 mg/100 ml. Blood ethanol levels should be

maintained at 100 to 130 mg/100 ml (21.7 to 28.2 mmol/L). It is safer to

maintain a blood ethanol concentration greater than 130 mg/100 ml than to have

it fall below 100 mg/100 ml.

»»Preparation from absolute ethanol: If single use vials of pyrogen free absolute ethanol are not available, tax-free bulk ethanol can be used, but it is not pyrogen free. A 0.22 micron filter should be used to minimise particulate matter. A 10% (V/V) solution can be prepared by any of the following methods:

⌂⌂ Remove 50 ml from 1 litre of 5%

ethanol solution and replace with 50 ml of abso-lute alcohol.

⌂⌂ Replace 100 ml of fluid from one

litre of dextrose 5% in water with 100 ml of absolute ethanol.

⌂⌂ Add 59 ml of absolute ethanol to

one litre of 5% ethanol solution.

⌂⌂ Add 112 ml of absolute ethanol to

one litre of dextrose 5% in water.

⌂⌂ Adding 59 ml of 95% ethanol

solution to one litre of 5% ethanol solution (if absolute alcohol is not

available).

⌂⌂ 59 ml of 95% ethanol provides 56

ml of ethanol (0.95 × 59 ml = 56 ml).

⌂⌂ One litre of 5% ethanol solution

provides 50 ml of ethanol (0.05 × 1000 ml = 50 ml).

⌂⌂ 56 + 50 = 106 ml of ethanol

divided by a total volume of 1059 ml = 10% (V/V).

»» Alternatively, 1 ml/kg of 95%

ethanol in fruit juice (180 ml) can be given orally over 30 minutes. For

maintenance, administer 0.17 to 0.28 ml/kg/hr as 50% ethanol in fruit juice.

»» If neither of these is

practicable, give 125 ml of a distilled alcoholic beverage (gin, vodka, whisky,

or rum) orally, diluted in glucose solution or juice, and repeat as required

cautiously.

–– Ethanol therapy should be

continued until the following criteria are met:

-- Methanol blood concentration,

measured by a reliable technique, is less than 10 mg/100 ml.

-- Formate blood concentration is

less than 1.2 mg/100 ml.

--Methanol-induced acidosis (pH,

blood gases), clinical findings (CNS), electrolyte abnormali-ties

(bicarbonate), serum amylase, and osmolal gap have resolved.

–– Patients who concurrently

ingested ethanol and methanol may have a normal acid-base profile despite a

dangerously elevated blood methanol level. Consider implementing the ethanol

treatment regimen in these patients until a methanol level can be determined.

Determine blood ethanol level before beginning ethanol therapy and modify the

loading dose accordingly.

In Western countries, a new antidote

has been intro-duced viz., 4 methyl

pyrazole (4MP), or fomepizole which does not cause CNS

depression (unlike ethanol). Upto 20 mg/kg of 4MP in divided doses have been

given for 5 days without any demonstrable toxicity. The usual dose is 15 mg/kg,

followed 12 hours later by 10 mg/kg 12th hourly for 4 doses, and then increased

to 15 mg/kg 12th hourly for as long as necessary. Fomepizole is easier to use

clinically, requires less monitoring, does not cause CNS depression or

hypoglycaemia, and may obviate the need for dialysis in some patients.

Sodium bicarbonate IV : 500 to 800 ml of 7.5%

solu-tion, slowly.

Folinic acid IV: 1 to 2 mg/kg, 6th hourly. It hastens theelimination of

formic acid. Folinic acid (5-formyltet-rahydrofolic acid, i.e. 5-FTHF), or

leucovorin or citrovorum factor is a biologically active form of folic acid

(pteroylglutamic acid) which is an essential water soluble vitamin.

For convulsions: Attempt initial

control with a benzodiaz-epine (diazepam or lorazepam). If seizures persist or

recur administer phenobarbitone.

Haemodialysis is very effective in

removing methanol, formaldehyde, and formic acid. While ethanol treatment is

also quite effective, it is extremely difficult to main-tain therapeutic

ethanol levels for long periods of time. Haemodialysis is strongly recommended

in patients with acidosis or serum methanol levels of greater than 25 to 50

mg/100 ml. Haemoperfusion is not effective. Peritoneal dialysis and continuous

venovenous haemofiltration are less effective.

Autopsy Features

· Cyanosis is very prominent,

especially in the upper parts of the body.

· Liver and kidneys show toxic damage.

· Lungs may reveal oedema,

emphysematous changes, and desquammation of alveolar epithelium.

· Eyes show evidence of retinal

oedema.

· Viscera must be preserved in

saturated solution of sodium chloride and not rectified spirit, as in the case

of all alcohols.

·

In addition to the routine viscera, it is advisable to

preserve one cerebral hemisphere.

Forensic Issues

Most

of the cases of methanol poisoning are accidental arising out of either an

alcoholic (deprived of ethanol for any reason) consuming methanol containing

products, or because of inten-tional adulteration of ethanol (especially

arrack) resulting in mass deaths. The latter are referred to quaintly as

“liquor trag-edies” and are reported in Indian newspapers at depressingly

regular intervals from all parts of the country.

Related Topics