Chapter: Modern Medical Toxicology: Neurotoxic Poisons: Inebriants

Ethanol: Diagnosis - Inebriant Neurotoxic Poisons

Diagnosis

·

Bedside test—Place 1 ml of unknown solution plus

1ml of acetic acid and 1 drop of H2SO4 in a test tube and

heat gently for 1 minute. A characteristic, strong fruity odour (due to ethyl

acetate) is positive for ethanol.

·

Blood alcohol level—The blood alcohol

concentration(BAC) estimated by immunoassay or gas chromatog-raphy is the

commonest method employed by labora-tories in India. Although accurate, the

results of these tests are often delayed several hours and are not really

appropriate in the clinical scenario.

·

Determine serum electrolytes, glucose, ethanol.

Hypoglycaemia, hypokalaemia, and metabolic acidosis (lactic or ketoacidosis)

may occur.

· BUN, creatinine, liver transaminases, and CPK may be useful in identifying secondary effects, such as hepato-toxicity (chronic ethanol use), respiratory depression, or rhabdomyolysis (if seizures are present).

·

Osmolality: Serum or plasma osmolality allows

estima-tion of blood ethanol level. A blood ethanol concentra-tion of 150 mg%

(32.5 mmol/L) increases osmolality by 21.6 milliosmoles/kg water. The following

equation is said to give good correlation with blood ethanol concentration: BAL

(g/L) = osmolal gap/27

·

Qualitative determination of urinary ethanol is commonly

included in a toxicology screen. However, urinary ethanol levels may be falsely

elevated in patients with diabetes.

Chronic Poisoning (Alcoholism,

Ethanolism):

Alcoholism

is a condition in an individual who consumes large amounts of alcohol over a

long period of time. It is characterised by

––

a pathological desire for alcohol intake –– black-outs during intoxication

–– withdrawal symptoms on ceasing alcohol

intake.

Unfortunately

many patients are not diagnosed correctly as alcoholics by their doctors. A

high index of suspi-cion is important, particularly in cases where there are

repeated consultations for vague symptoms or minor accidents. If in doubt, a

drinking history should be taken in which the patient is asked to describe a

typical week’s drinking.

–– Consumption should be quantified in terms of

units of alcohol. One unit* contains approximately 8 to 10 grams of alcohol and

is the equivalent of half a pint of beer, a single measure (30 ml) of spirits,

or a glass of table wine. Current opinion suggests that drinking becomes a

problem at levels above 21 units/week for men and 14 units/week for women.

Laboratory

tests are useful in confirming alcohol abuse.

Mean

corpuscular volume (MCV) or gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (gamma GT) is raised

in approximately 50% of problem drinkers.

Medical

complications of alcoholism:

–– GIT—gastritis, periodic diarrhoea,

increased inci-dence of oropharyngeal and oesophageal cancer.

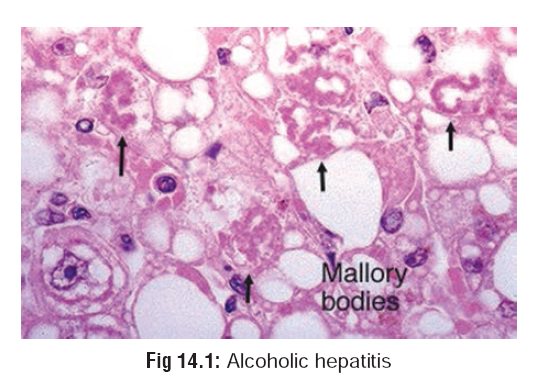

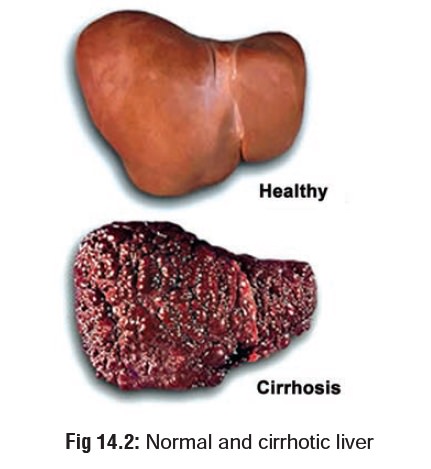

–– Liver—fatty liver with portal hypertension,

hepatitis (Fig 14.1), cirrhosis (Fig 14.2), increased incidence of

hepatic carcinoma.

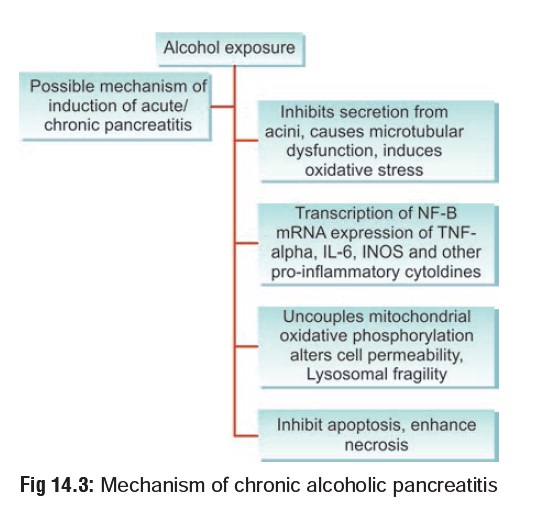

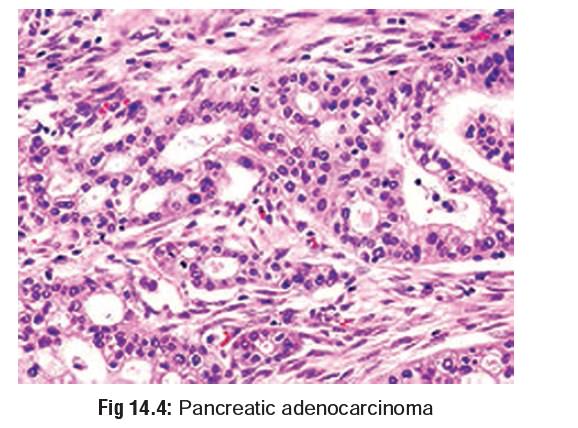

–– Pancreas—acute or chronic pancreatitis

(Fig 14.3), pancreatic cancer (Fig 14.4).

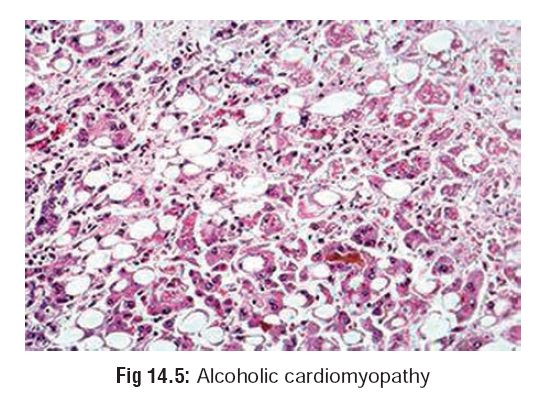

–– CVS—cardiomyopathy (Fig 14.5), dysrhythmias, hypertension.

–– CNS—polyneuropathy, cerebellar

degeneration, demyelination of corpus callosum (Marchiafava-Bignami disease),

amblyopia, stroke.

–– RS—aspiration pneumonia,

alcohol-induced asthma.

–– Endocrine—hypogonadism and

feminisation in males, amenorrhoea, menorrhagia, and infertility in females,

pseudo-Cushing syndrome.

––

Blood—anaemia, thrombocytopenia.

––

Skeletal muscle—myopathy.

–– Neuropsychiatric—memory disturbances

(amnesia, blackout), delusions, delirium tremens, Wernicke’s encephalopathy,

Korsakoff’s psychosis, dementia, alcoholic hallucinosis.

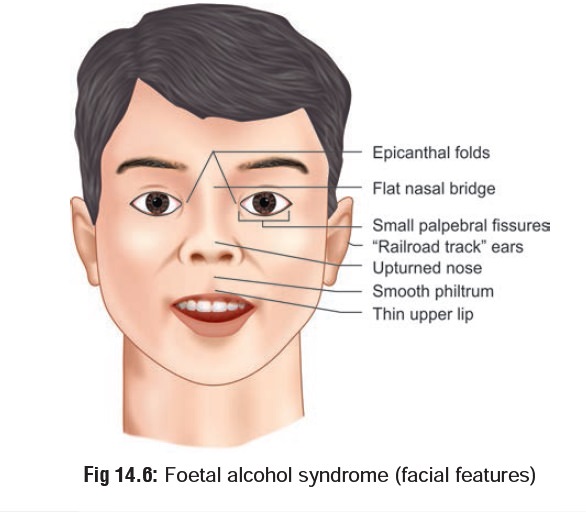

–– Teratogenecity—Foetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS)— this syndrome is characterised by facial dysmor-phias (Fig 14.6) and other congenital abnormalities, prenatal growth retardation, and neurodevelop-mental abnormalities, including developmental delay or mental retardation, in some children of mothers who abused ethanol during pregnancy.

Main abnormalities reported include cleft palate, spina bifida, ventricular and atrial septal defects, tetralogy of Fallot, pulmonary stenosis, and patent ductus arteriosus. Attention deficits, short-term memory, sequential processing deficits, and behavioural problems have been associated with FAS in school-age children.

–– Carcinogenicity—alcohol consumption

has been associated with various cancers, including liver cancer, oesophageal

cancer, breast and prostate cancer, and colorectal cancer.

--Distilled

liquors are more strongly linked with oesophageal cancers than wine or beer.

This may be due to an irritative effect of alcohol on the digestive tract.

--Studies

on the possible relationship between drinking and liver cancer have produced

mixed results: some have shown an association while others have not.

--Ethanol consumption has been

associated with a linear increase in breast cancer incidence in some studies.

--Ethanol has also been implicated

in increasing the risk of cancer of the larynx, oesophagus, mouth, and pharynx

in smokers. Ethanol should be regarded as a possible human co-carcinogen.

--Studies have also indicated a

positive asso-ciation between colorectal cancer and alcohol consumption, mainly

at high levels of alcohol consumption.

Withdrawal syndromes: Sudden

cessation of alcohol intake in a chronic alcoholic can provoke a withdrawal

reaction which may manifest as one of the following: –– Common abstinence

syndrome—

-- Onset : 6 to 8 hours after cessation of

alcohol.

--

Features: Tremor affecting hands, legs, and trunk (“the shakes”),

agitation, sweating, nausea, headache, insomnia.

–– Alcoholic hallucinosis— -- Onset : 24 to 36 hours.

--

Features: Objects appear distorted in shape, shadows seem to move, shouting

or snatches of music may be heard.

--Treatment:

Administration of phenothiazines(e.g. chlorpromazine 100 mg, 8th hourly).

––

Seizures (Rum fits)—

-- Onset : 7 to 48 hours.

--

Features: Clonic-tonic movements, with or without loss of consciousness.

–– Alcoholic ketoacidosis— -- Onset : 24 to 72 hours.

-- Features: Occurs during withdrawal as

well as after episodes of heavy drinking. In many cases there is a preceding

history of GI disturbance such as gastritis or pancreatitis which has led to

sudden diminution of alcohol intake. To compensate for the loss of

carbohydrates and depleted glycogen stores, the body mobilises fat from adipose

tissue as an alternative source of energy. There is a corresponding decrease in

insulin and an increased secretion of glucagon, catecholamines, growth hormone,

and cortisol.

Fatty acids are oxidised and the

final product, acetylcoenzyme A is converted to acetoacetate. This in turn is

converted to beta-hydroxybu-tyrate because of ethanol-induced low redox state.

Volume depletion in these patients inter-feres with the renal elimination of

acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate and contributes to the acidosis.

Paradoxically, the arterial pH may be normal due to a compensatory respiratory

alkalosis and a primary metabolic alkalosis due to vomiting. Clinical features

include drowsi-ness, confusion, tachycardia, and tachypnoea, progressing to

Kussmaul breathing pattern and coma.

-- Diagnosis:

»» Blood alcohol concentration is

typicallynot high.

»»

Blood glucose may be slightly elevated.

»» Since the nitroprusside reaction

detectsonly acetone and acetoacetate and not beta-hydroxybutyrate, the assay

for ketones is likely to be only weakly positive.

»» There is an elevated anion-gap

metabolicacidosis. Serum ketones are markedly elevated.

»» Hypokalaemia and hypochloraemia

areoften present.

-- Treatment:

»»

Correction of volume depletion—infusionof solutions of normal saline

with dextrose.

»»

Potassium supplementation may be required. »»

Thiamine (50 to 100 mg) to prevent devel-opment of Wernicke-Korsakoff

syndrome.

––

Delirium tremens (DTs)— -- Onset : 3 to 5 days.

-- Features: There is a dramatic onset of

disor-dered mental activity characterised by clouding of consciousness,

disorientation, and loss of recent memory. There are vivid hallucinations which

are usually visual, but sometimes audi-tory in nature. There is severe

agitation with restlessness and shouting, tremor, and truncal ataxia. Insomnia

is prolonged. Autonomic disturbances include sweating, fever, tachy-cardia,

hypertension, and dilated pupils. Dehydration and electrolyte disturbances are

characteristic. Blood testing shows leucocytosis and impaired liver function.

--Treatment:

»»Well lit, reassuring environment.

»»For agitation—diazepam 10 mg IV

initially, and then 5 mg every 5 minutes until full control, followed by 5 to

10 mg orally 3 times daily.

»»Thiamine in the usual dose.

»»Correction of fluid and electrolyte

imbal-ance.

–– Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome –

This is very rare as a withdrawal phenomenon, and is actually the result of

thiamine deficiency due to impoverished diet in an alcoholic.

--

Features: Wernicke’s encephalopathy is the acute form and is characterised

by drowsi-ness, disorientation, amnesia, ataxia, periph-eral neuropathy,

horizontal nystagmus, and external ocular palsies. It results from damage to

mammillary bodies, dorsomedial nuclei of thalamus, and adjacent areas of grey

matter. When recovery from Wernicke’s encephalop-athy is incomplete, a chronic

amnesic syndrome develops called Korsakoff’s psychosis which is characterised by

impairment of memory and confabulation (falsification of memory).

-- Treatment:

»» For Wernicke’s encephalopathy—

adminis-tration of thiamine 50 to 100 mg IV daily, infused slowly in 500 ml of

fluid for 5 to 7 days, and fluid replacement.

Treatment

Acute Poisoning (Intoxication,

Inebriation):

·

Airway protection, ventilatory

support.

·

Activated charcoal is NOT useful.

·

Stomach wash.

·

Thiamine 100 mg IV

·

Dextrose

–– Indications—If rapidly determined

bedside glucose level is less than 60 mg/100ml, or if rapid determi-nation is

not available.

–– Adult—25 grams (50 ml of 50% dextrose

solution) intravenously; may repeat as needed.

–– Paediatric—0.5 to 1 gram dextrose per

kg as 25% dextrose solution or 10% dextrose solution (2 to 4 ml/kg).

––

Precautions—Glucose administration should necessarily be preceded by

100 mg of thiamine IV or IM if chronic alcoholism or malnutrition is suspected,

to prevent development of Wernicke’s encephalopathy.![]()

·

Intravenous fluids.

·

A variety of drugs have been tried to hasten the elimi-nation

of ethanol or reverse its intoxicating effects, including naloxone,

physostigmine, and caffeine. None of them have been proved to be truly

effective. Recently, flumazenil (3 mg IV) has been shown to be effective (in

experimental studies) in reversing the respiratory depres-sion associated with

ethanol ingestion.

·

Haemodialysis can eliminate ethanol 3 to 4 times more

rapidly than liver metabolism. May be useful in patients with excessive blood

levels, impaired hepatic function and in those whose condition deteriorates in

spite of maximal supportive measures. However, it is unusual for dialysis to be

necessary to treat even severe ethanol intoxication.

Chronic Poisoning:

Treatment of withdrawal—apart from

the treatment measures outlined earlier (vide

supra), the following drugs have also been tried with varying degrees of

success:

–– Carbamazepine—It has been shown

to be effective in treating alcohol withdrawal, including delirium tremens.

–– Chlormethiazole—It is one of the

most popular drugs used for alcohol withdrawal abroad, and is administered in a

rapidly reducing dosage over 6 to 7 days. However it is itself associated with

a strong abuse potential.

–– Clonidine and

gamma-hydroxybutyric acid have also shown promising results in the treatment of

withdrawal symptoms. The former is given at a dose of 60 to 180 mcg/hr IV, and

the latter 50 mg/ kg, orally.

–– One of the most recent entrants

is tiapride, an atyp-ical neuroleptic agent which is a selective dopamine

D2-receptor antagonist. But it should be given only as an adjunct while

seizures, hallucinosis, etc., are being taken care of by other drugs. It is

effective in ameliorating psychologic distress associated with alcohol

abstinence. For delirium, the recommended dose is 400 to 1200 mg/day 6th

hourly, while the maintenance dose subsequently to help abstain from alcohol

should not exceed 300 mg/day.

Aversion therapy—The main aim in the

treatment of alcoholism is to gradually wean away the patient from the clutches

of ethanol, once the acute manifestations of withdrawal have been taken care

of. This process referred to quite loosely as de-addiction or detoxifi-cation,

should be undertaken only after admission to a hospital over a period of

several days, under close medical supervision. The insatiable craving for

alcohol that is often present must be tackled effectively, and![]() usually requires strongly deterrent measures. Many methods

have been tried in this connection, and one of the more succesful ways is to

administer a drug called disulfiram. It is a disulfide molecule

(tetraethylthiuram) which interferes with the oxidative metabolism of ethanol

at the acetaldehyde stage, as a result of which acetaldehyde accumulates

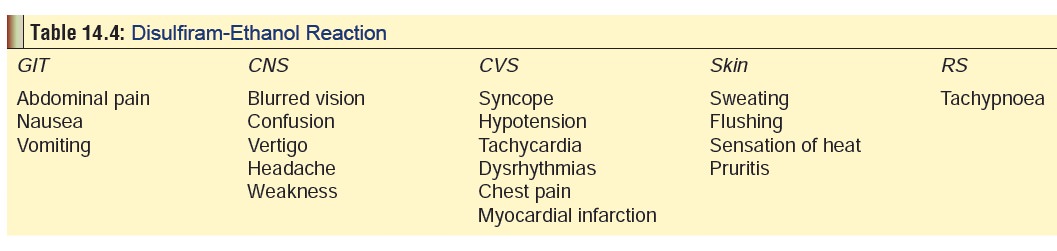

producing unpleasant symp-toms* (Table

14.4).

usually requires strongly deterrent measures. Many methods

have been tried in this connection, and one of the more succesful ways is to

administer a drug called disulfiram. It is a disulfide molecule

(tetraethylthiuram) which interferes with the oxidative metabolism of ethanol

at the acetaldehyde stage, as a result of which acetaldehyde accumulates

producing unpleasant symp-toms* (Table

14.4).

––Principles

of disulfiram therapy—

-- Ensure that the patient is off

alcohol for a minimum period of 12 hours before starting therapy.

-- Administer disulfiram only by the

oral route. -- Warn the patient explicitly that while he is on disulfiram,

alcohol must not be consumed even in small quantity since it can provoke a

severe (and sometimes fatal) reaction. He must also avoid taking medicinal

preparations containing alcohol, including topical preparations.

--The usual dose of disulfiram is

250 mg/day which may have to be taken for an indefinite period of time. Such

chronic use unfortunately often produces side effects like halitosis (rotten

egg odour due to sulfide metabolites), pruritis, headache, drowsiness,

impotence, peripheral neuropathies, depression, mania, psychosis, and

hepatotoxicity. The patient must be closely monitored and dosage reduced if

necessary.

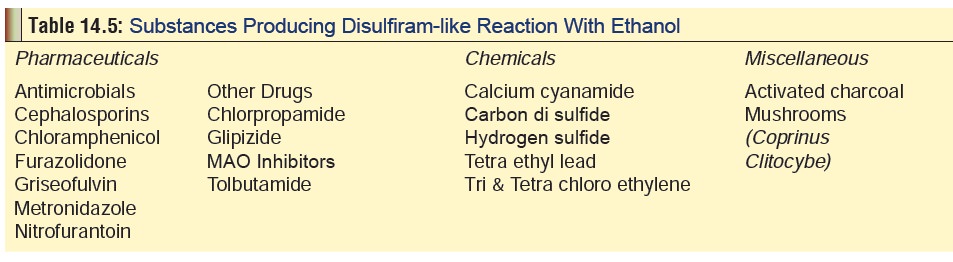

--Other than disulfiram, there are

numerous other substances which evoke a similar reaction with ethanol (Table 14.5).

Supportive psychotherapy—More than

individualised psychotherapy, it is group therapy which is effective in the

long, term management of abstinence. Groups provide an opportunity for

resocialisation and a sense of mutual commitment. Self-support organisations

such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA)

play an important role. The AA which had its origins in the USA in 1935 now has

more than 53,000 groups spread worldwide including India. The only requirement

for membership is a “desire to stop drinking”. There is no membership fee and

the organisation functions on a self-supporting basis through contributions

from the members. Local addresses of AA groups functioning in a given region

can be located in the telephone directory of that area. Meetings are generally

held once a week and are informal affairs conducted in a friendly atmosphere.

Generally two or three speakers share their experi-ences during each session

relating to their addiction and recovery.

Related Topics