Chapter: The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology: Zoogeography

Major ecological divisions - Marine fishes

Major ecological divisions

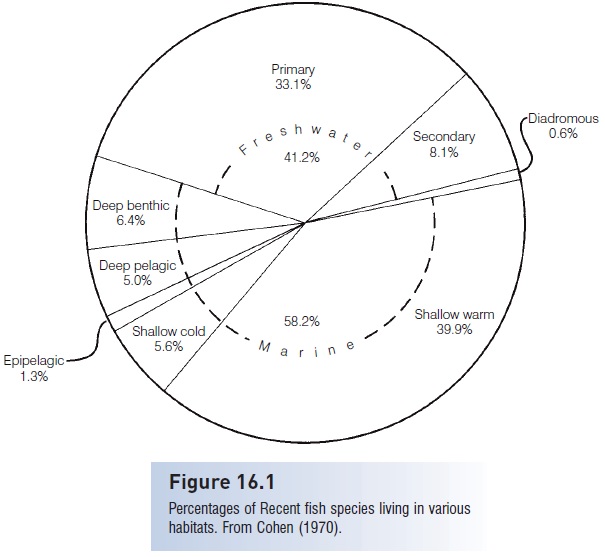

Four main ecological divisions are recognized among the 16,000+species of marine fishes:

1 Epipelagic fishes, which dwell from the surface down to 200 m, make up 1.3% of the total, or about 360 species.

2 Deep pelagic fishes include about 1400 species, or about 5% of the total. These water column dwelling fishes can be further subdivided into mesopelagic fishes, which live between 200 and 1000 m, and deeper dwelling bathypelagic fishes.

3 Deep benthic fishes comprise about 1800 species, or 6.4% of the total.

4 Littoral or continental shelf species are shallowdwelling fishes that inhabit the shore and shelf above 200 m. They are the largest group, constituting 45% of the total, or about 12,600 species.

Epipelagic fishes

The diversity and adaptations of surface-dwelling fishes are treated (The open sea), so attention here will focus on their zoogeography. Many epipelagic species are worldwide in distribution. However, many inshore epipelagic species have more restricted distributions. One member of a family may be confined to one side of an ocean and be represented by another, allopatric species (a closely

Figure 16.1

Percentages of Recent fish species living in various habitats. From Cohen (1970).

As examples, consider the distribution patterns of some tunas (Scombridae), halfbeaks (Hemiramphidae), and needlefishes (Belonidae). Most species of tunas of the genusThunnus are widespread offshore. Several species, including Albacore (T. alalunga), Yellowfin (T. albacares), and Bigeye (T. obesus) have continuous distributions, indicating that genetic interchange occurs among populations in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans. Little tunas of the genus Euthynnus have a different distribution pattern, more closely associated with the shore. One species occurs in the Atlantic (E. alletteratus), one in the Indo-West Pacific (E. affinis), and one in the eastern Pacific (E. lineatus). Among Spanish mackerels, Scomberomorus, distributions of species are even more shore associated, with allopatric species in the Atlantic, Indo-West Pacific, and eastern Pacific (Collette & Russo 1985b).

Turning to halfbeaks (Hemiramphidae), species of the genus Hemiramphus are more widespread than species of the more inshore genus Hyporhamphus. For example, two species of Hemiramphus are found on both sides of the Atlantic, and one species (He. far) is widespread throughout the Indo-West Pacific (and has even invaded the eastern Mediterranean Sea through the Suez Canal). In contrast, all species of Hyporhamphus in the western Atlantic differ from those in the eastern Atlantic, Indo-West Pacific, and eastern Pacific.

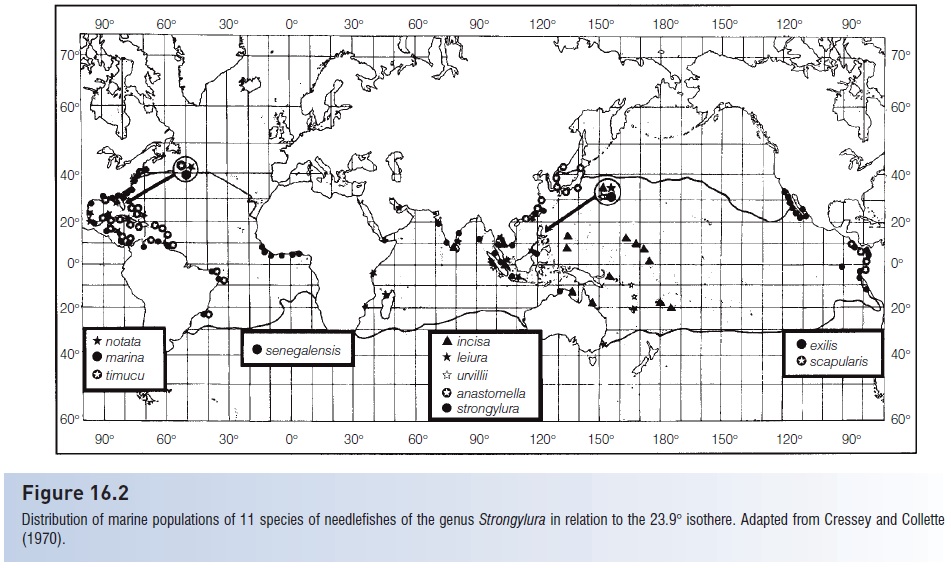

Similarly, needlefishes (Belonidae) of the genera Ablennes and Tylosurus are much more widespread than species of the genus Strongylura (Cressey & Collette 1970).Ablennes is worldwide, and two species of Tylosurus (T. acus and T. crocodilus) are nearly worldwide, with different subspecies recognized in parts of their ranges. Species of Strongylura are more numerous and have more restricted distributions, like species of Hyporhamphus.

Distributions of epipelagic inshore fishes may be limited by temperature, either directly or indirectly. For example, for needlefishes (Fig. 16.2), a clear relationship exists between temperature and the northernmost and southernmost distribution records of species of Strongylura.

Deepwater fishes

Many species of deep water fishes (see The deep sea) are also widespread. In looking at their distributions, we cannot rely on surface maps, because ocean basins may have underwater sills, ridges that act as barriers to the distribution of deep water fishes. Sills act as barriers because they physically inhibit the movement of fishes and they also restrict the mixing of waters. For example, the Mediterranean Sea is continuous with the Atlantic Ocean at the surface via the 12.9 km wide Straits of Gibraltar. However, at 1200 m, the Mediterranean Sea is 14°C, whereas the adjacent Atlantic Ocean is 2.5°C at the same depth and these depths are interrupted by a 286 m deep sill. Another sill at 350 m separates the western from the eastern Mediterranean at the Strait of Sicily (Patarnello et al. 2007). Similarly, the Red Sea is 23°C at 125 m, whereas the Indian Ocean is 2.5°C at the same depth, but the two areas are separated by a shallow sill. Deep water fishes adapted to the cool temperatures of the Atlantic and Indian oceans may not be able to penetrate the Mediterranean and Red seas because they cannot tolerate the warm temperatures at the sill that separates the ocean from the adjacent sea.

Figure 16.2

Distribution of marine populations of 11 species of needlefishes of the genus Strongylura in relation to the 23.9° isothere. Adapted from Cressey and Collette (1970).

Littoral fishes

Temperature is also a major limiting factor for the distribution of shallow water fishes. The greatest diversity of marine fish species is in tropical waters. Part of this great biodiversity is associated with the coral reefs that provide habitat for the fishes and their prey. Reef-building corals are restricted to depths above 100 m in clear waters warmer than 18°C; corals reach their maximum extent at 23–25°C. Common groups of coral reef fishes include moray eels (Muraenidae); squirrelfishes (Holocentridae); several families of percoids such as seabasses (Serranidae), grunts (Pomadasyidae and Haemulidae), snappers (Lutjanidae), cardinalfishes (Apogonidae), and butterfl yfishes (Chaetodontidae); and some more advanced families such as damselfishes (Pomacentridae), wrasses (Labridae), parrotfishes (Scaridae), gobies (Gobioidei), blennies (Blennioidei), surgeonfishes (Acanthuridae), triggerfishes (Balistidae), and boxfishes (Ostraciidae).

Related Topics