Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Principles and practice of medicine and surgery

Intravenous fluids - Fluid and electrolyte balance

Intravenous fluids

Intravenous fluids may be necessary for rapid fluid replacement, e.g. in

a shocked patient, or for maintenance in patients who are unable to eat and

drink or who are unable to maintain adequate intake in the face of large

losses, e.g. due to diarrhoea. When prescribing intravenous fluids certain

points should be remembered:

·

Are intravenous fluids the best

form of fluid replacement? If possible, oral fluids are preferable or if

swal-low is impaired consider nasogastric administration, which has the

advantage of allowing nasogastric feed to be given to provide nutrition.

·

Which intravenous fluid should be

given? Ideally this should be the one that matches any fluid and electrolyte

deficit or losses most closely. For example, blood loss should be replaced with

a blood transfusion and salt and water loss (e.g. vomiting, diarrhoea) with

normal saline. Additional potassium replacement is often needed in bowel

obstruction, but may be dangerous in renal failure.

·

In calculating the volume

required for maintenance check if is there increased insensible loss, e.g. due

to sweating in pyrexial patients, or are there other fluids being administered

which need to be taken into account? For example, some patients are on

intravenous drugs or intravenous nutritional supplements (total parenteral

nutrition).

·

Patients at risk of cardiac

failure (elderly, cardiac disease, liver or renal impairment) require special

caution as they are more prone to develop fluid overload.

There is no universally applicable fluid regimen. The choice of fluid

given and the rate of administration depend on the patient, any continued

losses and all patients must have continued assessment of their fluid balance

using fluid balance charts, observations and clinical examination as well as

monitoring of serum electrolytes by serial blood tests.

Fluid preparations: Intravenous fluid has to be isotonic to lysis of red blood cells. The

administration of water alone would lead to water moving across cell membranes

by osmosis, such that the cells would swell up and burst. Giving hypertonic

fluid is equally dangerous, as it causes water to move out of cells.

·

Most intravenous fluids used are

crystalloids (saline, dextrose, combined dextrose/saline, Hartmann’s solution).

It should be remembered that dextrose is rapidly metabolised by the liver;

hence giving dextrose solution is the equivalent of giving water to the

extra-cellular fluid compartment. If insufficient sodium is given in

conjunction, or the kidneys do not excrete the free water, hyponatraemia

results. This is a common problem, often because of inappropriate use of

dextrose or dextrosaline and because stress from trauma or surgery as well as

diseases such as cardiac failure promote antidiuretic hormone (ADH) release.

This leads to a mild form of syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone

(SIADH;) where there is water retention by the kidneys with resulting

hyponatraemia.

·

Colloids (albumin, dextran or

gelatin-based fluids) contain high-molecular-weight components that tend to be

retained in the intravascular compartment. This increases the colloid osmotic

pressure (oncotic pressure) of the circulation and draws fluid back into the

vascular compartment from the extracellular space. A smaller volume of colloid

compared to crystalloid is needed to have the same haemodynamic effect.

Theoretically they are of benefit for rapid expansion of the intravascular

compartment; however, they have anti-coagulant, antiplatelet and fibrinolytic

effects, which may be undesirable. There has been no consistent demonstrable

benefit of using colloid over crystalloid in most circumstances. In addition,

the use of albumin solution in hypoalbuminaemic patients (which seems logical)

has been associated with increased pulmonary oedema, possibly due to rapid

haemodynamic changes or capillary leakage of albumin.

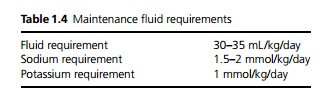

Fluid regimens: These should consist of maintenance

fluids (which covers normal urinary, stool and insensible losses) and

replacement fluids for additional losses and to correct any pre-existing

dehydration. Fluid regimens must also take into account that patients of

differing

weight have different fluid and electrolyte requirements (see Table

1.4). Potassium is added to intravenous fluids in patients who are not being

fed, although this should be done with care. Both hypokalaemia and

hyper-kalaemia are potentially

life-threatening and serum potassium must be checked daily in patients who are

given potassium replacement. Patients with acute or chronic renal failure

should not have potassium added routinely to fluid replacement (although

hypokalaemia should of course be treated). Rapid administration of potassium is

dangerous, so even in hypokalaemia no more than 10 mmol/h is recommended

(except in severe hypokalaemia within an intensive care setting) and the

potassium must be uniformly mixed in the bag.

A typical daily maintenance regime for a 70 kg man with normal cardiac

and renal function consists of 8 hourly bags of:

·

1 L of 0.9% saline with 20 mmol

KCl added,

·

1 L of 5% dextrose with 20 mmol

KCl added and

·

1 L of 5% dextrose with 20 mmol

KCl added.

In general, dextrosaline is not suitable for maintenance, as it provides

insufficient sodium and tends to cause hyponatraemia. Postoperative patients

are also more prone to hyponatraemia due to mild SIADH, so may require

proportionally more sodium, e.g. 2 L of 0.9% saline to 1 L of 5% dextrose.

Replacement fluids generally need to be 0.9% saline, as losses tend to have a

high sodium concentration, e.g. drain fluid, blood, vomitus and diarrhoea.

Fluids should not be prescribed without taking into account the

patient’s current fluid balance, continued losses and underlying coexistent

diseases. It should also be remembered that intravenous fluids do not provide

any significant nutrition.

Related Topics