Chapter: Ophthalmology: Conjunctiva

Infectious Conjunctivitis

Infectious Conjunctivitis

The normal conjunctiva contains

microorganisms. Inflammation usually occurs as a result of infection from direct contact with pathogens (such as

from a finger, towel, or swimming pool) but also from complicating factors (such as a compromised immune system or

injury). There are significant regional differences in the spectrum of

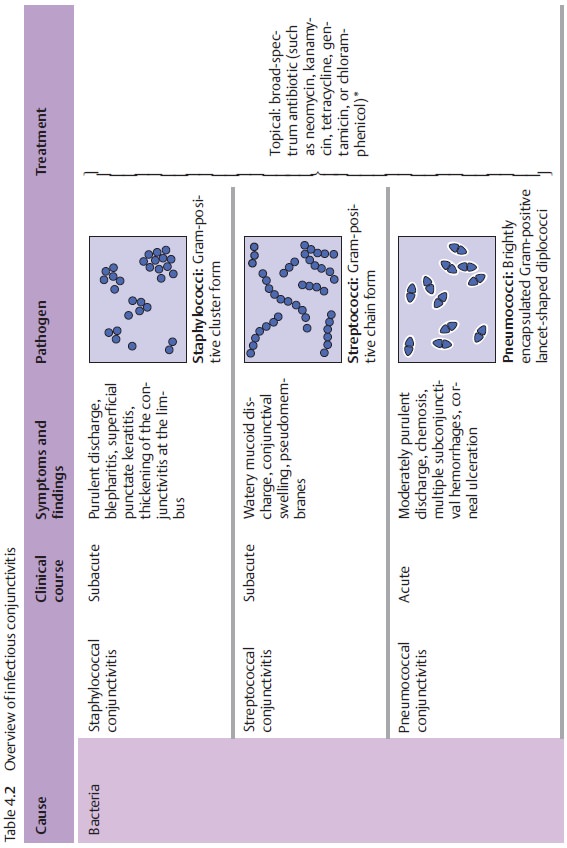

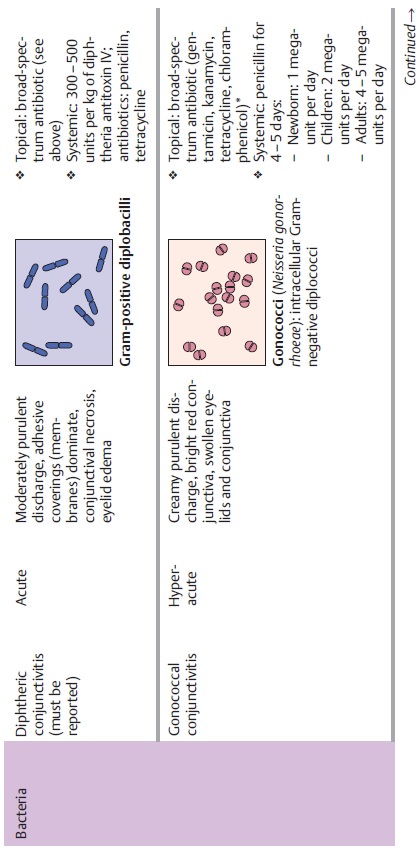

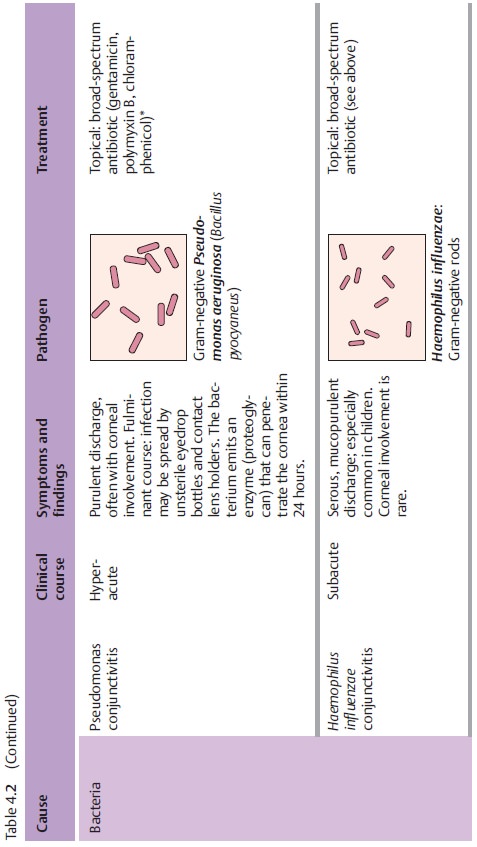

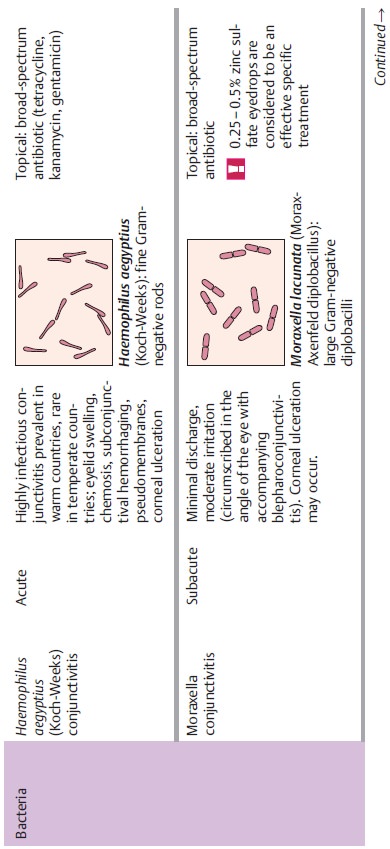

pathogens. Table 4.2 provides an overview of pathogens, symptoms, and treatments.

Bacterial Conjunctivitis

Epidemiology: Bacterial conjunctivitis is very frequently encountered.

Etiology: Staphylococcus, streptococcus, and pneumococcus infections

aremost common in temperate countries.

Symptoms: Typical symptoms include severe reddening, swelling of the

con-junctiva, and purulent discharge that leads to formation of yellowish

crusts.

Diagnostic considerations: Bacterial conjunctivitis can usually be reliablydiagnosed from

the presence of typical symptoms. Laboratory tests (conjunc-tival smear) are

usually only necessary when the conjunctivitis fails to respond to antibiotic

treatment.

Bacterial conjunctivitis is diagnosed on the

basis of clinical symptoms.

Smears are obtained only in severe, uncertain,

or persistent cases.

Treatment: Bacterial conjunctivitis usually responds very well to

antibiotictreatment. A wide range of well tolerated, highly effective antibiotic agents is available today.

Most of these are supplied as ointments (which are longer acting and suitable

for overnight therapy) and as eyedrops for topical

therapy. Substances include gentamicin, tobramycin, Aureomycin,

chloramphenicol,1 neomycin, polymyxin B in combination with bacitracin and

neomycin , Ter-ramycin, kanamycin, fusidic acid, ofloxacin, and acidamphenicol.1

Preparations that combine an antibiotic and cortisone can more rapidlyalleviate subjective symptoms

when findings are closely monitored. These include medications such as

gentamicin and dexamethasone; neomycin, polymyxin B, and dexamethasone; or

tetracycline, polymyxin B, and hydro-cortisone.

In severe, uncertain, or persistent cases

requiring microbiological exami-nation to identify the pathogen, treatment with

broad-spectrum antibiotics or topical antibiotic combination preparations that

cover the full range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens should begin

immediately. This method is necessary because microbiological identification of

the pathogen and resistance testing of the antibiotic are not always successful

and may require several days. It is not advisable to leave the conjunctivitis

untreated for this period.

In the presence of severe, uncertain, or

persistent conjunctivitis, treat-ment with broad-spectrum antibiotics or

topical antibiotic combination preparations should be initiated immediately,

even before the labora-tory results are available.

Clinical course and prognosis: Bacterial conjunctivitis usually responds wellto antibiotic

treatment and remits within a few days.

Chlamydial Conjunctivitis

Chlamydia are Gram-negative bacteria.

Inclusion Conjunctivitis

Epidemiology: Inclusion conjunctivitis isvery

frequentin temperate coun-tries. The incidence in western industrialized

countries ranges between 1.7% and 24% of all sexually active adults depending

on the specific population studied.

Etiology: Oculogenital infection (Chlamydia

trachomatisserotype D–K) isalso caused by direct contact. In the newborn

(see neonatal conjunctivitis), this occurs at birth through the cervical

secretion. In adults, it is primarily transmitted during sexual intercourse,

and rarely from infection in poorly chlorinated swimming pools.

Symptoms: The eyes are only moderately red and slightly sticky from

viscousdischarge.

Diagnostic considerations: Tarsal follicles are observed typically on theupper and lower

eyelids, and pannus will be seen to spread across the limbus of the cornea. As

this is an oculogenital infection, it is essential to determine whether the

mother has any history of vaginitis, cervicitis, or urethritis if there is

clinical suspicion of neonatal infection. Gynecologic or urologic examination

is indicated in appropriate cases. Chlamydia may be detected in conjunctival

smears, by immunofluorescence, or in tissue cultures. Typical cytologic signs

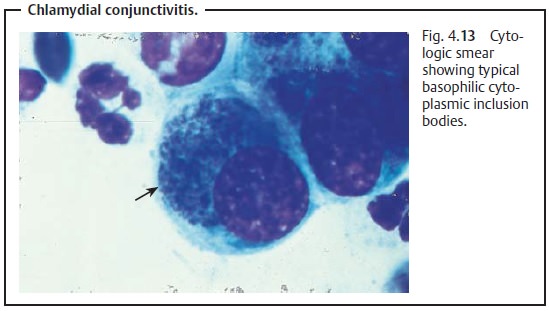

include basophilic cytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Fig. 4.13).

Treatment: In adults, the disorder is treated with tetracycline or erythromy-cin eyedrops or ointment over a period of four to six weeks. The oculogenital mode of infection entails a risk of reinfection. Therefore, patients and sexual partners of treated patients should all be treated simultaneously with oral tetracycline. Children should be treated with erythromycin instead of tetracy-cline (see the table in the Appendix for side effects of medications).

Prognosis: The prognosis is good when the sexual partner is included in

ther-apy.

Trachoma

Trachoma (Chlamydia

trachomatis serotype A–C) is rare in temperate coun-tries. In endemic

regions (warm climates, poor standard of living, and poor hygiene), it is among

the most frequent causes of blindness (see Table 4.2 for symptoms, findings, and therapy). Left

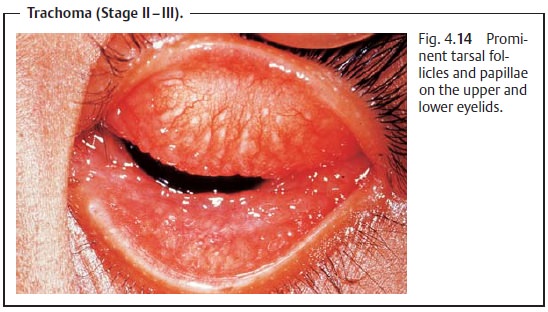

untreated, the disorder progresses through four stages (Fig. 4.14):

❖ Stage I: Hyperplasia of the lymph follicles on the

upper tarsus.

❖ Stage II: Papillary hypertrophy of the upper tarsus, subepithelial

cornealinfiltrates, pannus formation, follicles on the limbus.

❖ Stages III and IV: Increasing scarring and symptoms of keratoconjunctivi-tis

sicca. The progression is entropion, trichiasis, keratitis, superinfection,

ulceration, perforation, and finally loss of the eye.

Viral Conjunctivitis

Epidemiology: The incidence ofepidemic keratoconjunctivitisis high ingeneral, and it is by far the most frequently encountered viral conjunctivitis (see Table 4.2)

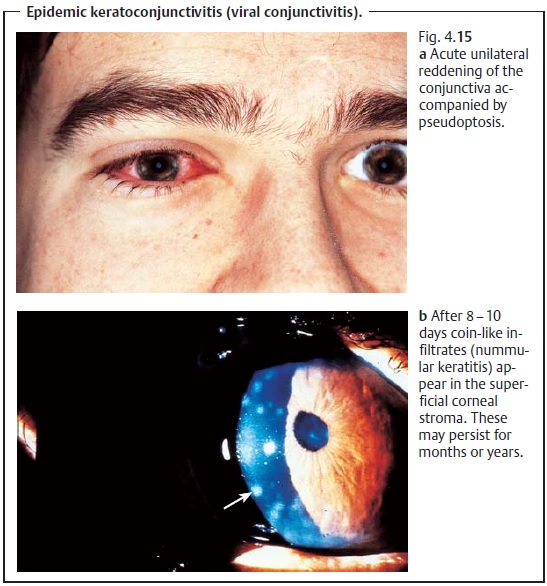

Etiology: This highly contagious conjunctivitis is usually caused by type

18 or19 adenovirus and is spread by direct contact (see also prophylaxis; Figs.

4.15a and b). The incubation period is eight to ten days.

Symptoms: Onset is usually unilateral. Typical signs include severe

illacri-mation and itching accompanied by a watery mucoid discharge. The eyelid

and often the conjunctivitis are swollen. Patients often also have a moderate

influenza infection.

Diagnostic considerations: Characteristic findings include reddening andswelling of the plica semilunaris and lacrimal caruncle and nummular ker-atitis (Fig. 4.15b) after 8 – 15 days, during the healing phase..

Differential diagnosis: The disease runs a well defined clinical course that isnearly

impossible to influence and resolves after two weeks. No specific ther-apy is

possible. Treatment with artificial tears and cool compresses helps relieve

symptoms. Cortisone eyedrops should usually be avoided as they can compromise

the immune system and prolong the clinical symptoms.

Prophylaxis: This is particularly important. Because the disease is spread bycontact,

the patient should refrain from rubbing his or her eyes despite a severe

itching sensation and avoid direct contact with other people such as shaking

hands, sharing tools, or using the same towels or wash cloths, etc.

Special hygiene precautions should be taken when examining patients with

epidemic keratoconjunctivitis in ophthalmologic care facilities and doc-tors’

offices to minimize the risk of infecting other patients. Patients with

epi-demic keratoconjunctivitis should not be seated in the same waiting room as

other patients. They should not be greeted with a handshake, and they should be

requested to refrain from touching objects where possible. Examination should

be by indirect means only, avoiding applanation tonometry, contact lens examination,

or gonioscopy. After examination, the examiner should clean his or her hands

and the work site with a surface disinfectant.

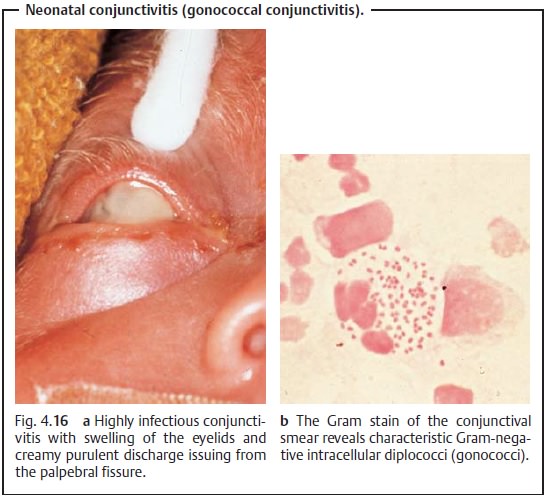

Neonatal Conjunctivitis

Epidemiology: Approximately 10% of the newborn contract conjunctivitis.

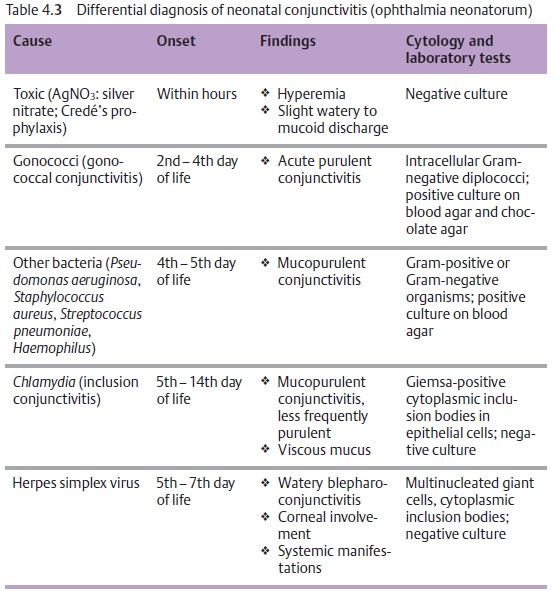

Etiology (Table 4.3): The most

frequent pathogens areChlamydia,followedby

gonococci. Neonatal conjunctivitis is less frequently attributable to otherbacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Haemophilus, Staphylococcus aureus and

Streptococcus pneumoniae, or to herpes simplex. The infectionoccurs at

birth. Chlamydia infections are particularly important because they are among

the most common undetected maternal genital diseases in Europe, affecting 5% of

all pregnant women. Neonatal conjunctivitis some-times occurs as a result of Credé’s

method of prophylaxis with silver nitrate, required by law in Europe to prevent

bacterial infection.

Symptoms: Depending on the pathogen, the inflammation will manifestitself

between the second and fourteenth day of life (Table 4.3). The spectrum ranges from mild conjunctival irritation to

life-threatening infection (especially with gonococcal infection).

Conjunctivitis as a result of Credé’s method of prophylaxis appears with hours

but only leads to mild conjunctival irritation.

Acute purulent conjunctivitis in the newborn (gonococcal conjunctivi-tis) is considered a medical emergency. The patient should be referred to an ophthalmologist for specific diagnosis.

Diagnostic considerations: The tentative clinical diagnosis is made on thebasis of the

onset of the disease (Table 4.3) and

the clinical syndrome. For example, gonococcal infections (gonococcal

conjunctivitis) are typified by particularly severe accumulations of pus (Figs.

4.16a and b). The newborn’s eyelid are tight and swollen because the pus

accumulates under them. When the baby’s eyes are opened, the pus can squirt out

under pressure and cause dangerous conjunctivitis in the examiner’s own eyes.

The examiner should always wear eye protection in the presence of sus-pected gonococcal conjunctivitis to guard against infection from pus issuing from the newborn’s eyes. Gonococci can penetrate the eye even in the absence of a corneal defect and lead to loss of the eye.

The diagnosis should be confirmed by cytologic

and microbiological studies. However, these studies often fail to yield

unequivocal results, so that treat-ment must proceed on the basis of clinical

findings.

Differential diagnosis: The onset of the disease is crucial to differential diag-nosis

(Table 4.3). Neonatal conjunctivitis

must be distinguished from neonatal dacryocystitis. This disorder differs from

the specific forms of con-junctivitis in it only becomes symptomatic two to

four weeks after birth, with reddening and swelling of the region of the

lacrimal sac and purulent dis-charge from the puncta. It can be readily

distinguished from neonatal con-junctivitis because of these symptoms.

Treatment: Toxic conjunctivitis(Credé’s method of prophylaxis): When theeye

is regularly flushed and the eyelids cleaned, symptoms will abate

spon-taneously within one or two days.

Gonococcal conjunctivitis: Topical administration of broad-spectrum anti-biotics

(gentamicin eyedrops every hour) and systemic penicillin (penicillin G IV 2

mill. IU daily) or cephalosporin in the presence of penicillinase-produc-ing

strains.

Chlamydial conjunctivitis: Systemic erythromycin and topical erythromy-cin eyedrops five

times daily. There is a risk of recurrence where the dosage or duration of

treatment is insufficient. It is essential to examine the parents and include

them in therapy.

Herpes simplex conjunctivitis: Therapy involves application of acyclovirointment to the

conjunctival sac and eyelids as herpes vesicles will usually be present there,

too. Systemic acyclovir therapy is only required in severe cases.

Prophylaxis: Credé’s method of prophylaxis(application of 1% silver nitratesolution)

prevents bacterial inflammation but not chlamydial or herpes infec-tion.

Prophylaxis of chlamydial infection consists of regular examination of the

woman during pregnancy and treatment in appropriate cases.

Parasitic and Mycotic Conjunctivitis

Parasitic and mycotic forms of conjunctivitis

(see Table 4.2) are less

important in temperate climates. They are either very rare or occur primarily as co-morbidities associated with a

primary corneal disorder, such as mycotic infections of corneal ulcers.

Related Topics