Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Common Medical Problems in Pregnancy

Hematologic Disease: Anemia

HEMATOLOGIC DISEASE

Anemia

The plasma and cellular

composition of blood change sig-nificantly during pregnancy, with the expansion

of plasma volume proportionally greater than that of the red blood cell mass.

On average, there is a 1000-mL increase in plasma volume and a 300-mL increase

in red-cell volume (a 3:1 ratio). Because the hematocrit (Hct) reflects the

pro-portion of blood made up primarily of red blood cells, Hct demonstrates a

“physiologic” decrease during pregnancy; therefore, this decrease is not

actually an anemia.

Anemia in

pregnancy is generally defined as an Hct less than 30% or a hemoglobin of less

than 10 g/dL.

The direct fetal consequences of

anemia are minimal, although infants born to mothers with iron deficiency may

have diminished iron stores as neonates. The maternal consequences of anemia

are those associated with any adult anemia. If anemia is corrected, the woman

with an ade-quate red-cell mass enters labor and delivery better able to

respond to acute peripartum blood loss and to avoid the risks of blood or blood

product transfusion.

IRON-DEFICIENCY ANEMIA

Iron-deficiency

anemia is by far the most frequent type ofanemia seen in

pregnancy, accounting for more than 90% of cases. Because the iron content of

the standard American diet and the endogenous iron stores of many American

women are not sufficient to provide for the increased iron requirements of

pregnancy, the National Academy of Sciences recommends 27 mg of iron

supplementation (present in most prenatal vitamins) daily for pregnant women.

Most prescription prenatal vitamin/mineral prepa-rations contain 60 to 65 mg of

elemental iron.

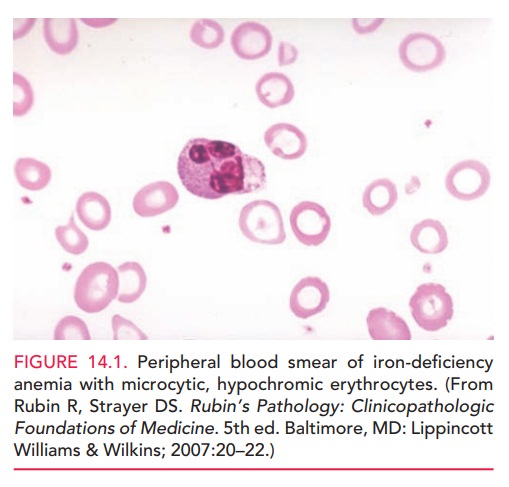

All pregnant women should be

screened for iron-deficiency anemia. Severe iron-deficiency anemia is

charac-terized by small, pale erythrocytes (Fig. 14.1) and red-cell indices

that indicate a low mean corpuscular volume and low mean corpuscular hemoglobin

concentration. Addi-tional laboratory studies usually demonstrate decreased

serum iron levels, an increased total iron-binding capacity, and a decrease in

serum ferritin levels. A recent dietary history is obviously important,

especially if pica (the con-sumption of non-nutrient substances such as starch,

ice, or dirt) exists. Such dietary compulsions may contribute to iron

deficiency by decreasing the amount of nutritious food and iron consumed.

Treatment of iron-deficiency

anemia generally requires an additional 60 to 120 mg of elemental iron per day,

in ad-dition to the iron in the prenatal vitamin/mineral prepa-ration. Iron

absorption is facilitated by or with vitamin C supplementation or ingestion

between meals or at bed-time on an empty stomach. The response to therapy is

first seen as an increase in the reticulocyte count approximately 1 week after

starting iron therapy. Because of the plasma expansion associated with

pregnancy, the Hct may not increase significantly, but rather stabilizes or

increases only slightly.

FOLATE DEFICIENCY

Adequate intake of folic acid (folate) has been found to reduce the risk of neural tube defects (NTDs) in the fetus

The first occurrence of NTDs may

be reduced by as much as 36% if women of reproductive age consume 0.4 mg of

folate daily both before conception and during the first trimester of

pregnancy. The Recommended Daily Dietary Allowance for folate for pregnant

women is 0.6 mg. Folate deficiency is especially likely in multiple gestations

or when patients are taking anticonvulsive medications. Women with a history of

a prior NTD-affected pregnancy or who are being treated with anticonvulsive

drugs may reduce the risk of NTDs by more than 80% with daily intake of 4 mg of

folate in the months in which conception is attempted and for the first

trimester of pregnancy.

Folate is found in green leafy vegetables and is now an added supplement in cereal, bread, and grain prod-ucts. These supplements are designed to enable women to easily consume 0.4 mg to 1 mg of folate daily. Prescription prenatal vitamin/mineral preparations contain 1 mg of folic acid.

OTHER ANEMIAS

The hemoglobinopathies are a heterogenous group of single-gene

disorders that includes the structural hemoglo-bin variants and the

thalassemias. Hereditary

hemolyticanemias are also rare causes of anemia in pregnancy.Some examples

are hereditary spherocytosis, an autosomal dominant defect of the erythrocyte

membrane; glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency; and pyruvate kinase

deficiency.

Related Topics