Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Common Medical Problems in Pregnancy

Cardiac Disease during pregnancy

CARDIAC DISEASE

With earlier diagnoses and more

effective treatments, more women with congenital and acquired heart disease

reach adulthood and may become pregnant. Patients with rheumatic heart disease

(caused by untreated or delayed treatment of group A–hemolytic streptococcal

[GAS] ton-sillopharyngitis) and acquired infectious valvular heart dis-ease

(often associated with drug use) comprise only 50% of pregnant cardiac

patients. The remainder consists of other cardiac conditions that traditionally

have been less commonly seen in pregnancy. Because

pregnancy is itselfassociated with an increase in cardiac output of 40%, the

risks to mother and fetus are often profound for women with pre-existing

cardiac disease. Ideally, cardiac patients should havepreconceptional care

directed at maximizing cardiac func-tion. They should also be counseled about

the risks their particular heart disease poses in pregnancy.

Classification of Heart Diseases in Pregnancy

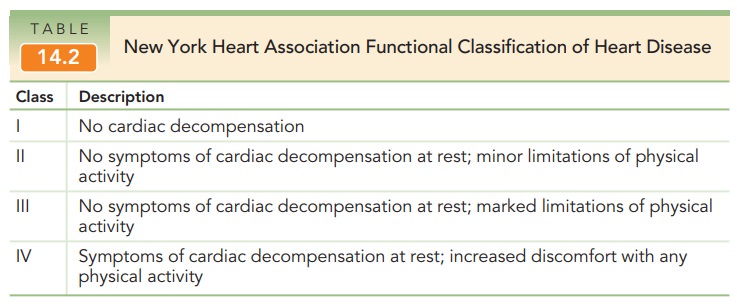

The classification of heart

disease by the New York Heart Association is useful to evaluate all types of

cardiac patients with respect to pregnancy (Table 14.2). It is a functional

classification and is independent of the type of heart dis-ease. Patients with

septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus, and mild mitral and aortic valvular

disorders often are in classes I or II and tend to do well throughout

pregnancy. Primary pulmonary

hypertension, uncorrected tetralogy of Fallot, Eisenmenger syndrome, Marfan

syndrome with significant aortic root dilation, and certain other conditions

are associated with a much worse prognosis (frequently death) through the

course of pregnancy. For this reason, patients with such disorders are strongly

advised not to become pregnant.

Management

General management of the pregnant cardiac patient con-sists of avoiding conditions that add additional stress to the workload of the heart beyond that already imposed by preg-nancy, including prevention and/or correction of anemia, prompt recognition and treatment of any infections, a de-crease in physical activity and strenuous work, and proper weight gain. Adequate rest is essential. For patients with class I or II heart disease, increased rest at home is advised; and in cases of higher class levels, hospitalization and treatment of cardiac failure may be required. Coordinated management between obstetrician, cardiologist, and anes-thesiologist is especially important for patients with sig-nificant cardiac dysfunction.

The fetuses of patients with

functionally significant cardiac disease are at increased risk for low birth

weight and prematurity. A patient with

congenital heart disease is1% to 5% more likely to have a fetus with congenital

heart disease than is someone without this condition; antepartum fetal cardiac

assessment using ultrasound is recommended.

The antepartum management of

pregnant cardiac pa-tients includes serial evaluation of maternal cardiac

status as well as fetal well-being and growth. Anticoagulation, antibiotic

prophylaxis for subacute bacterial endocarditis, invasive cardiac monitoring,

and even surgical correction of certain cardiac lesions during pregnancy can

all be ac-complished if necessary. The intrapartum and postpartum management of

pregnant cardiac patients includes consid-eration of the increased stress of

delivery and postpartum physiologic adjustment. Labor in the lateral position

to fa-cilitate cardiac function is often desirable. Every attempt is made to

facilitate vaginal delivery because of the in-creased cardiac stress of

cesarean section. Because cardiac output increases by 40% to 50% during the

second stage of labor, shortening this stage by the use of forceps or vac-uum

extractor is often advisable. Epidural anesthesia to re-duce the stress of

labor is also recommended. Even with patients who are stable at the time of

delivery, cardiac out-put increases in the postpartum period because of the

ad-ditional 500 mL added to the maternal blood volume as the uterus contracts.

Indeed, most obstetric patients who die with cardiac disease do so following

delivery.

Rheumatic

heart disease remains a common cardiacdisease in pregnancy. As the severity of the associated valvu-lar

lesion increases, the risk for thromboembolic disease, subacute bacterial

endocarditis, cardiac failure, and pulmonary edema increases. A high rate of

fetal loss also occurs in women with rheumatic heart disease. Approximately

90% of these pa-tients have mitral stenosis, whose associated mechanical

obstruction worsens as cardiac output increases during pregnancy. Women with

mitral stenosis associated with atrial fibrillation have an especially high

risk of develop-ing congestive heart failure.

Maternal

cardiac arrhythmias are occasionally en-countered

during pregnancy. Paroxysmal atrial

tachycardia is the most commonly encountered maternal arrhythmia and is usually

associated with overly strenuous exercise. Underlyingcardiac disease such

as mitral stenosis should be suspected when atrial fibrillation and flutter are

encountered.

Peripartum

cardiomyopathy is an unusual but espe-cially severe cardiac

condition identified in the last month of pregnancy or the first 6 months

following delivery. It is difficult to distinguish from other cardiomyopathies

(e.g., myocarditis) except for its association with pregnancy. In many cases,

no apparent cause can be determined. Treatment

is generally unchanged from cardiac failure un-associated with pregnancy,

except that the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors is avoided if

the patient is pregnant. Management includes bed rest, digoxin, diuretics,

and, in some cases, anticoagulation. The mortality rate is high and is related

to cardiac size 6 to 12 months later. If cardiac size returns to normal,

prognosis is improved, although it remains guarded. Sterilization counseling is

warranted for patients with cardiomyopathy.

Related Topics