Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Streptococci and Enterococci

Group A Strepto Coccal Infections : Clinical Aspects

GROUP A STREPTO COCCAL INFECTIONS : CLINICAL ASPECTS

MANIFESTATIONS

Streptococcal Pharyngitis

Although it may occur at any age, streptococcal pharyngitis is most frequent between the ages of 5 and 15 years. The illness is characterized by acute sore throat, malaise, fever, and headache. Infection typically involves the tonsillar pillars, uvula, and soft palate, which become red, swollen, and covered with a yellow-white exudate. The cervical lymph nodes that drain this area may also become swollen and tender. Group A strepto- coccal pharyngitis is usually self-limiting. Typically, the fever is gone by the third to fifth day, and other manifestations subside within 1 week. Occasionally the infection may spread locally to produce peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscesses, otitis media, suppu- rative cervical adenitis, and acute sinusitis. Rarely, more extensive spread occurs, produc- ing meningitis, pneumonia, or bacteremia with metastatic infection in distant organs. In the preantibiotic era, these suppurative complications were responsible for a mortality of 1 to 3% following acute streptococcal pharyngitis. Such complications are much less common now, and fatal infections are rare.

Impetigo

The primary lesion of streptococcal impetigo is a small (up to 1 cm) vesicle sur-rounded by an area of erythema. The vesicle enlarges over a period of days, becomes pustular, and eventually breaks to form a yellow crust. The lesions usually appear in 2- to 5-year-old children on exposed body surfaces, typically the face and lower extremities. Multiple lesions may coalesce to form deeper ulcerated areas. Although S.aureus produces a clinically distinct bullous form of impetigo , it canalso cause vesicular lesions resembling streptococcal impetigo. Both pathogens are isolated from some cases.

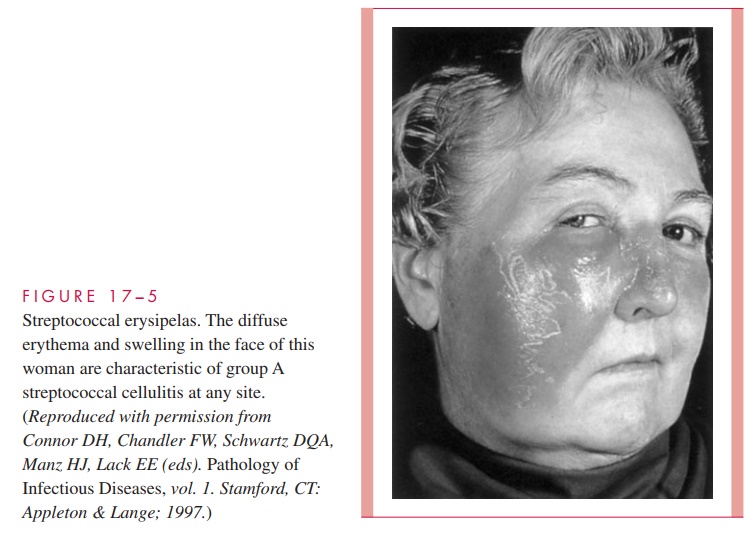

Erysipelas

Erysipelas is a distinct form of streptococcal infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissues, primarily affecting the dermis. It is characterized by a spreading area of erythema and edema with rapidly advancing, well-demarcated edges, pain, and systemic manifestations, including fever and lymphadenopathy. Infection usually occurs on the face (Fig 17 – 5), and a previous history of streptococcal sore throat is common.

Puerperal Infection

Infection of the endometrium at or near delivery is a life-threatening form of group A streptococcal infection. Fortunately, it is now relatively rare, but in the 19th century, the clinical findings of “childbed fever” were characteristic and common enough to provide the first clues to the transmission of bacterial infections in hospitals . Other organisms can cause puerperal fever, but this form is the most likely to produce a rapidly progressive infection.

Disease Associated with Streptococcal Pyrogenic Exotoxins

Scarlet Fever

Infection with strains that elaborate any of the SPEs may superimpose the signs of scarlet fever on a patient with streptococcal pharyngitis. In scarlet fever, the buccal mucosa, temples, and cheeks are deep red, except for a pale area around the mouth and nose (circumoral pallor). Punctate hemorrhages appear on the hard and soft palates, and the tongue becomes covered with a yellow-white exudate through which the red papillae are prominent (strawberry tongue). A diffuse red “sandpaper” rash appears on the second day of illness, spreading from the upper chest to the trunk and extremities. Circulating anti-body to the toxin neutralizes these effects. For unknown reasons, scarlet fever is both less frequent and less severe than early in the 20th century.

Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome (STSS)

STSS may begin at the site of any group A streptococcal infection even at the site of seem-ingly minor trauma. The systemic illness starts with vague myalgia, chills, and severe pain at the infected site. Most commonly, this is in the skin and soft tissues and leads to necro-tizing fasciitis and myonecrosis. The striking nature of this progression when it involves the extremities is the basis of the label “flesh-eating bacteria.” STSS continues with nau-sea, vomiting, and diarrhea followed by hypotension, shock, and organ failure. The out-standing laboratory findings are a lymphocytosis; impaired renal function (azotemia); and, in over half the cases, bacteremia. Some patients are in irreversible shock by the time they reach a medical facility. Many survivors have been left as multiple amputees as the result of metastatic spread of the streptococci.

Poststreptococcal Sequelae

Acute Rheumatic Fever (ARF)

ARF is a nonsuppurative inflammatory disease characterized by fever, carditis, subcu- taneous nodules, chorea, and migratory polyarthritis. Cardiac enlargement, valvular murmurs, and effusions are seen clinically and reflect endocardial, myocardial, and epicardial damage, which can lead to heart failure. Attacks typically begin 3 weeks (range, 1 to 5 weeks) after an attack of group A streptococcal pharyngitis, and in the absence of antiinflammatory therapy last 2 to 3 months. ARF also has a predilection for recurrence with subsequent streptococcal infections as new M types are encoun- tered. The first attack usually occurs between the ages of 5 and 15 years. The risk of recurrent attacks after subsequent group A streptococcal infections continues into adult life and then decreases. Repeated attacks lead to progressive damage to the endo- cardiumand heartvalves,withscarringand valvular stenosis orincompetence (rheumatic heart disease).

Acute Glomerulonephritis

Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis is primarily a disease of childhood that begins 1 to 4 weeks after streptococcal pharyngitis and 3 to 6 weeks after skin infection. It is charac-terized clinically by edema, hypertension, hematuria, proteinuria, and decreased serum complement levels. Pathologically, there are diffuse proliferative lesions of the glomeruli. The clinical course is usually benign, with spontaneous healing over weeks to months. Occasionally, a progressive course leads to renal failure and death.

DIAGNOSIS

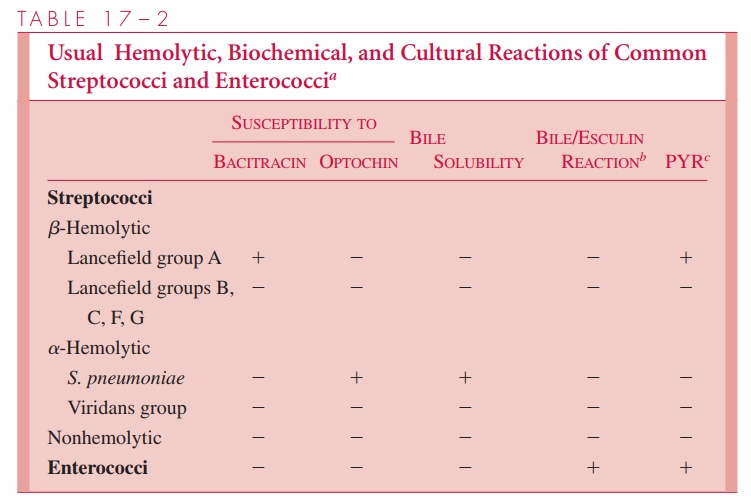

Although these clinical features of streptococcal pharyngitis are fairly typical, there is enough overlap with viral pharyngitis that a culture of the posterior pharynx and tonsils is required for diagnosis. A direct Gram-stained smear of the throat is unhelpful because of the other streptococci in the pharyngeal flora, but smears from normally sterile sites usually demonstrate streptococci. Blood agar plates incubated anaerobically give the best yield be-cause they favor the demonstration of -hemolysis (see streptolysins, above). β-hemolytic colonies are identified by Lancefield grouping using immunofluorescence or agglutination methods. In smaller laboratories, an indirect method based on the exquisite susceptibility of group A strains to bacitracin and the relative resistance of strains of other groups may be used for presumptive separation of group A strains from the others (Table 17 – 2).

Detection of group A antigen extracted directly from throat swabs is now available in a wide variety of kits marketed for use in physicians’ offices. These methods are rapid and specific, but most are only 90 to 95% sensitive compared to culture. Given the importance of the detection of group A streptococci in prevention of ARF (the reason physicians cul-ture sore throats), missing even 5% of cases is not tolerable. Until direct antigen detection methods gain a higher sensitivity, negative results must be confirmed by culture before withholding treatment. Some of the newer antigen detection procedures are approaching a sensitivity that would allow their substitution for culture.

Several serologic tests have been developed to aid in the diagnosis of poststreptococ-cal sequelae by providing evidence of a previous group A streptococcal infection. They include the ASO, anti-DNAase B, and some tests that combine multiple antigens. High titers of ASO are usually found in sera of patients with rheumatic fever, so that test is used most widely.

TREATMENT

Group A streptococci are highly susceptible to penicillin G, the antimicrobic of choice. Concentrations as low as 0.01 μg/mL have a bactericidal effect, and penicillin resistance is so far unknown. Numerous other antimicrobics are also active, including other penicillins, cephalosporins, tetracyclines, and macrolides, but not aminoglycosides.

Patients allergic to penicillin are usually treated with erythromycin if the organisms are susceptible. Impetigo is often treated with erythromycin to cover the prospect of S. aureus involvement. Adequate treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis within 10 days of onset prevents rheumatic fever by removing the antigenic stimulus; its effect on the duration of the pharyngitis is less, because of the short course of the natural infection. Treatment does not prevent the development of acute glomerulonephritis.

PREVENTION

Penicillin prophylaxis with long-acting preparations is used to prevent recurrences of ARF during the most susceptible ages (5 to 15 years). Patients with a history of rheumatic fever or known rheumatic heart disease receive antimicrobial prophylaxis while undergo-ing procedures known to cause transient bacteremia, such as dental extraction. Vaccines using epitopes of the M protein molecule, which would provide protection against acute infection without stimulating autoantibodies are in development. This is a sizable task given the large number of M protein serotypes.

Related Topics