Chapter: Biotechnology Applying the Genetic Revolution: Inherited Defects

Genetic Screening and Counseling

GENETIC SCREENING AND COUNSELING

As explained earlier, close

relatives are more likely to produce malformed children because of harmful

recessive alleles coming together. It is also true that two people from

otherwise unrelated families that both have a history of the same hereditary

disease might be wise to avoid having children. Today we can do more than give

general advice. Testing of prospective parents for high-risk genetic diseases

can now be done for an increasing number of genes. The typical approach is to

use a hybridization probe or PCR analysis. This will reveal whether a mutant

copy of the gene is present in a DNA sample from the person tested. If marital

partners both test positive for a recessive defect, they will have to decide

whether or not to take the risk of having children. For a recessive defect,

where both parents are carriers, one in four children will get the disease.

The basic problem with

genetic screening is that our ability to detect genetic defects has far outrun

our ability to cure them. Thus, screening may reveal a defect about which

nothing can be done, and this may cause severe psychological distress to the

individuals concerned. For example, Huntington’s disease is an autosomal

dominant condition that results in movement disorder, dementia, and ultimately

death. The symptoms usually appear only in the 30s, although they may be

delayed as late as the 60s in some patients. Genetic screening helps those who

are afflicted decide whether or not to have children. It also provides them

with the knowledge that they will eventually develop an incurable and fatal

disease. Some cancers and coronary heart disease have a genetic component

(often multigenic). Screening may allow affected individuals to avoid factors

that tend to trigger the disease. On the other hand, especially if the

treatment is complicated and/or only partially effective, such knowledge may be

a burden.

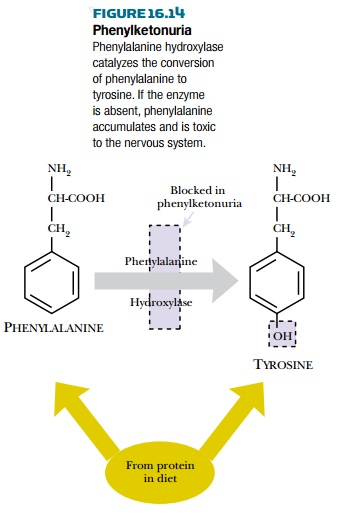

Genetic screening sometimes allows successful intervention by modifying diet or lifestyle. The classic case is phenylketonuria. The absence of the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase causes a buildup of phenylalanine and a deficiency of the product, tyrosine (Fig. 16.14). Excess phenylalanine is neurotoxic; if untreated, this condition results in severe damage to the central nervous system, and patients require permanent care for life. However, a diet low in phenylalanine avoids the buildup of this amino acid and largely alleviates the problems. Phenylketonuria occurs in 1 in 10,000 live births and is routinely screened for in developed nations using blood samples taken a week or so after birth. The diet may be relaxed somewhat later in life after development of the nervous system is largely complete.

Given that a reliable test is

available, it is generally agreed that neonatal screening is justified if the

disease is reasonably frequent (say 1 in 10,000 or more), the disease is

severely damaging, and that treatment is available that significantly improves

the condition.

It is also possible to

examine embryos during early pregnancy by drawing samples of amniotic fluid

which contain some cells from the fetus, a procedure called amniocentesis, or by examining

extraembryonic fetal tissue. These

cells may be genetically screened to see, for example, if the fetus is

homozygous for a recessive defect. Embryos doomed to grow up with hereditary

defects could then be aborted early if the parents wish to do so. It is also

now possible to screen embryos obtained by in

vitro fertilization before they are implanted. This avoids aborting of an

unwanted fetus should a serious genetic defect be discovered.

Related Topics