Chapter: Basic Radiology : Gastrointestinal Tract

Gastrointestinal Tract: Normal Imaging

NORMAL IMAGING

Upper Gastrointestinal Tract

The organs that can be examined

in the upper gastrointesti-nal tract include the pharynx, esophagus, stomach,

and duo-denum. The pharynx and esophagus may be evaluated separately or as part

of more complete examinations of these organs. Various techniques are available

to assess the func-tion and structure of the pharynx depending on the

indica-tions for the examination. Motion recording (now using mainly digital

technology) of pharyngeal function and im-aging of pharyngeal structures are

often combined for a more thorough examination. Also, materials of variable

vis-cosity can be used in patients to determine aspiration risk and dietary

needs; the latter is often called a “modifiedbarium swallow” and is done in

conjunction with a swallow-ing therapist. An alternate method of assessing

swallowing is fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), which is

also performed by a swallowing therapist with training in this technique.

Pharyngeal function is complex

and is best evaluated with motion-recording techniques that allow slow-motion

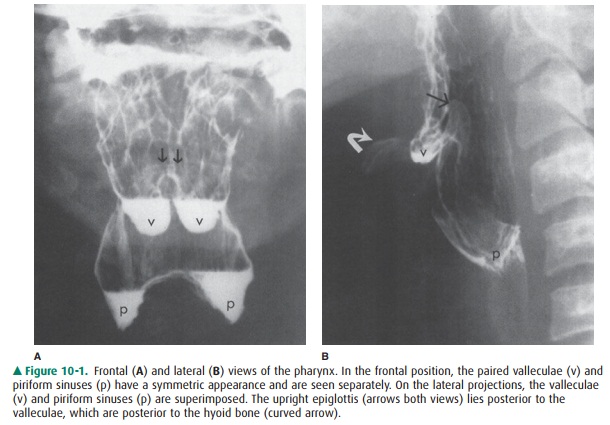

review. Imaging of the pharynx is usually done with the patient in the frontal

and lateral positions (Figure 10-1). In the frontal view, the paired valleculae

and piriform sinuses are sepa-rated. The lateral view of the pharynx

superimposes these structures, but permits better visualization of the base of

the tongue, hyoid bone, and epiglottis anteriorly, and the poste-rior

pharyngeal wall and cervical spine posteriorly.

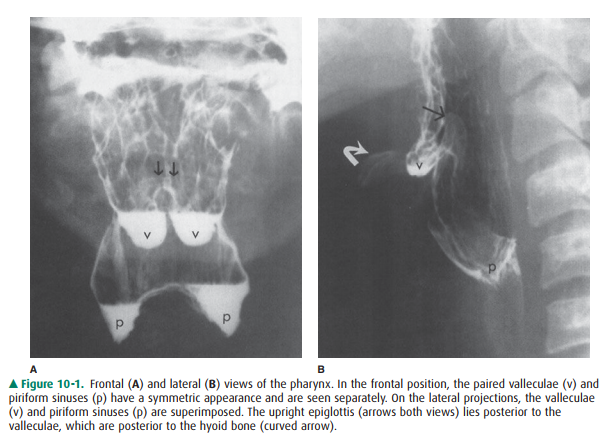

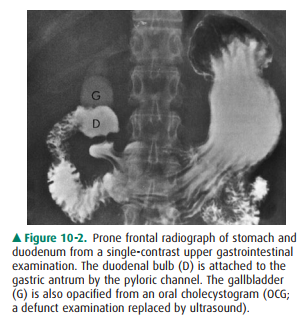

The esophagus, stomach, and

duodenum are usually ex-amined together as part of the upper gastrointestinal

series. A variety of radiographic techniques are used and usually com-bined to

optimize the upper gastrointestinal examination; techniques include observation

of esophageal motility, film-ing of the organs with varying amounts of barium

suspen-sion, gas, or air, and obtaining views of the mucosal surface (Figures

10-2, 10-3). The upper gastrointestinal tract is bestexamined by luminal

contrast studies or endoscopy because mucosal abnormalities are often the cause

of disease. CT and MR imaging can also evaluate these organs and detect focal

masses, wall thickening, and extrinsic processes, such as an invasive

pancreatic malignancy. These modalities can also contribute to the staging of

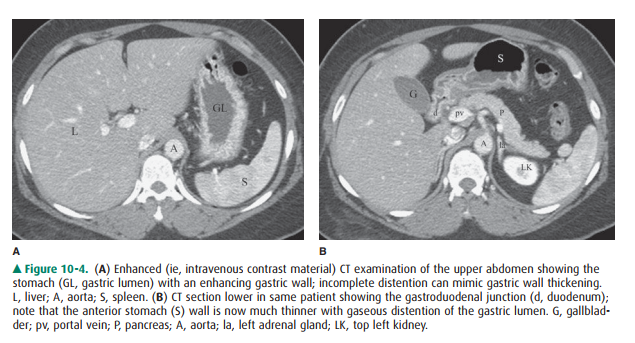

malignancies, especially in the esophagus (Figure 10-4).

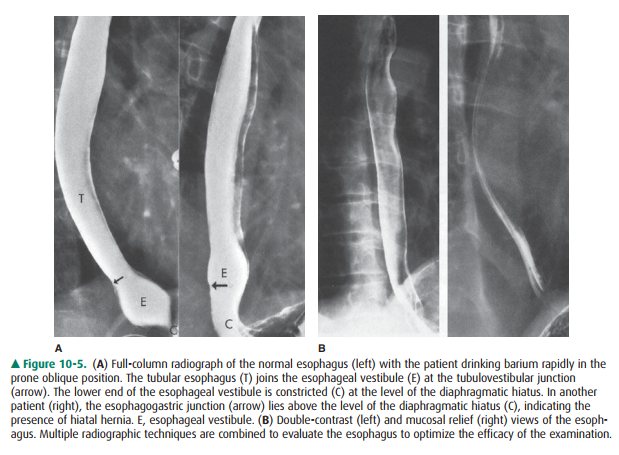

The esophagus consists mainly of

a tubular portion with a bell-shaped termination called the esophageal vestibule. The esophagogastric junction normally lies within or below the esophageal hiatus.

When the esopha-gogastric junction lies above the hiatus, hiatal hernia is

present, which is the most common structural abnormality of the upper

gastrointestinal tract (Figure 10-5 A). The esophageal mucosal surface has a

smooth appearance when distended and shows smooth, thin longitudinal folds when

collapsed (Figure 10-5 B). Esophageal peristalsis can be ob-served by having

the patient swallow single volumes of bar-ium suspension.

The stomach has a complex shape

and varies considerably depending on the degree of distention (see Figures

10-2, 10-3). When the stomach is collapsed, the rugal folds are seen

prominently and may mimic focal or diffuse gastric disor-ders, whether on

luminal contrast or CT studies. With gastric distention, the rugal folds are

flattened and the mucosal sur-face of the stomach is seen more effectively.

Barium studies of the upper gastrointestinal tract evaluate gastric function

poorly; radionuclide gastric emptying studies are more effec-tive for this

purpose.

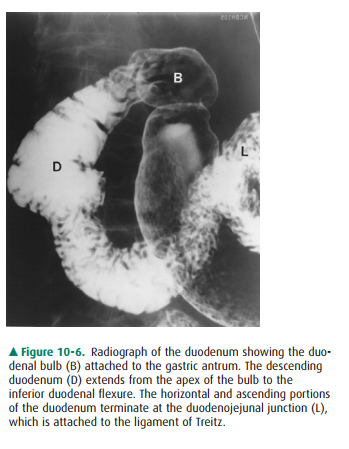

The duodenum is attached to the

stomach at the narrow pylorus and consists of the duodenal bulb and the

de-scending and ascending portions, although a horizontal segment is often added

(Figure 10-6; see Figure 10-4 B). The duodenum terminates at the duodenojejunal

junction, which is attached to the ligament of Treitz. The duodenal bulb has a

triangular or heart-shaped appearance normally tapering to the apex of the bulb

with its junction to the de-scending portion. The bulbar mucosal surface is

normally smooth. The duodenum assumes a C-shape configuration within the upper

abdomen, and the mucosal folds are sym-metric. The duodenum is surrounded by

many structures, particularly the pancreas, and is often involved secondarily

by diseases in other adjacent organs; cross-sectional CT or MR imaging is

useful in demonstrating this involvement (see Figure 10-4).

Small Intestine

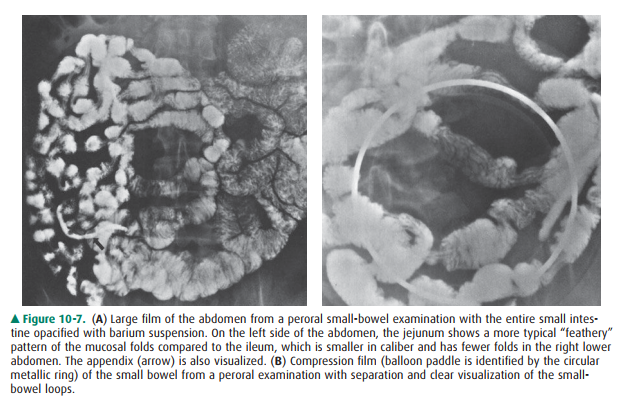

The radiographic examination of

the small bowel evaluates the mesenteric portion of the organ, which consists

of the jejunum and ileum. The following luminal contrast meth-ods can be used

to examine the small intestine: (1) peroral small-bowel series; (2)

enteroclysis; and (3) various retro-grade techniques (eg, via an ileostomy).

The peroral small-bowel series is often done immediately after an upper

gastrointestinal examination and following ingestion of additional barium

suspension. Serial images of the ab-domen are obtained, and abdominal

compression applied to better visualize the small-bowel loops, including the

terminal ileum (Figure 10-7). However, the peroral small-bowel study is

probably the least effective method of exam-ining this organ; techniques that

better distend the small bowel with higher volume are now preferred depending

on the indications. These include enteroclysis and CT or MR imaging with volume

instillation by oral ingestion or via a tube, that is, CT or MR enterography or

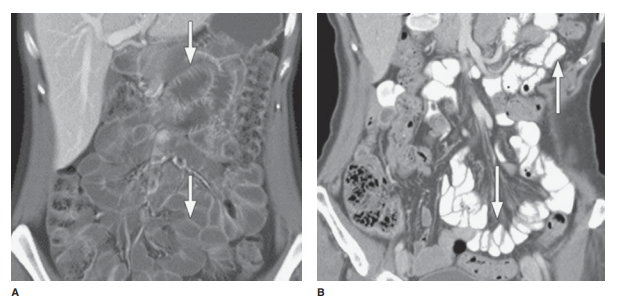

CT or MR entero-clysis (Figure 10-8).

Enteroclysis is an intubated

examination of the small in-testine and can be done by a variety of techniques

and using a number of different modalities (as discussed earlier). The small

intestine is intubated by a nasal or oral route with a small-bore enteric tube

placed with fluoroscopic guidance. A variety of luminal contrast methods exist,

but filming is done similarly to the peroral examination. The enteroclysis

tech-niques permit better control of small-bowel distention and more exact

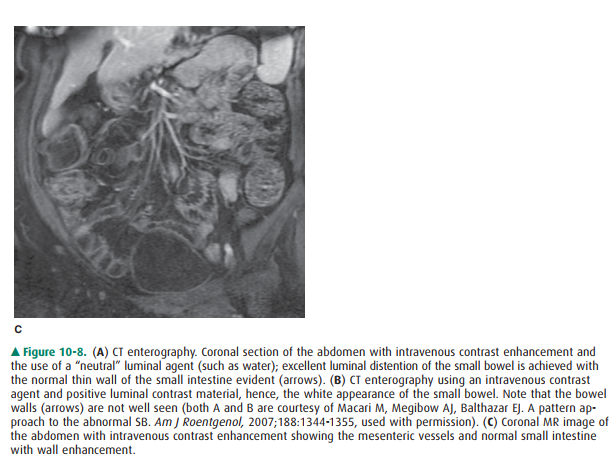

visualization of small-bowel loops (Figure 10-9).

Retrograde examination of the

small bowel involves filling of the organ from the opposite direction. Various

techniques can be used depending on the patient’s anatomy. Reflux of the small

intestine through the ileocecal valve can be done as part of a barium enema. If

the patient has an ileostomy, various devices can be introduced into the ostomy

site and a barium suspension instilled directly.

The length of the mesenteric

small bowel in adults aver-ages about 20 feet, but varies considerably among

individ-uals. The jejunum comprises just over one-third of the length and the

ileum the remainder, although no discrete transition is seen between the two

segments. The normally distended small bowel has a caliber of 2 to 3 cm, being

slightly larger more orad in the jejunum. Depending on the degree of

distention, the mucosal folds (valvulae con-niventes) may have a feathery

appearance or may be trans-versely oriented across the intestinal lumen with

more complete distention. The mucosal folds are more numerous in the jejunum

and gradually decrease in number and size in the ileum.

Large Intestine

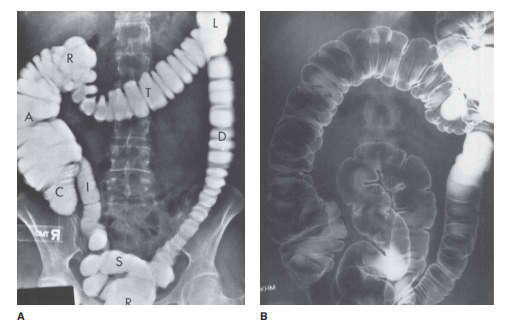

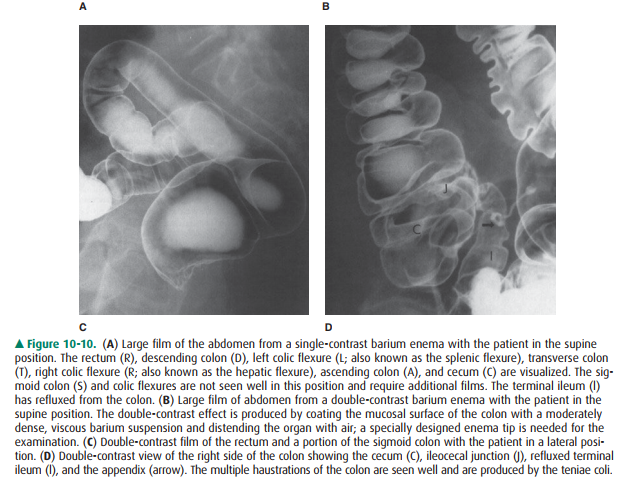

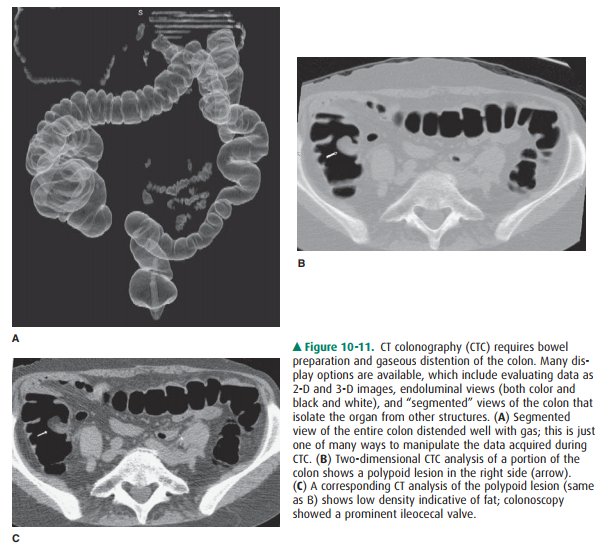

The radiographic examination of

the large bowel evaluates the entire organ from the rectum to the cecum. Reflux

of bar-ium suspension into the ileum and the appendix, if present, occurs

commonly. The colon can be evaluated by several techniques, which include

single-contrast and double-contrast barium enemas; different types of rectal

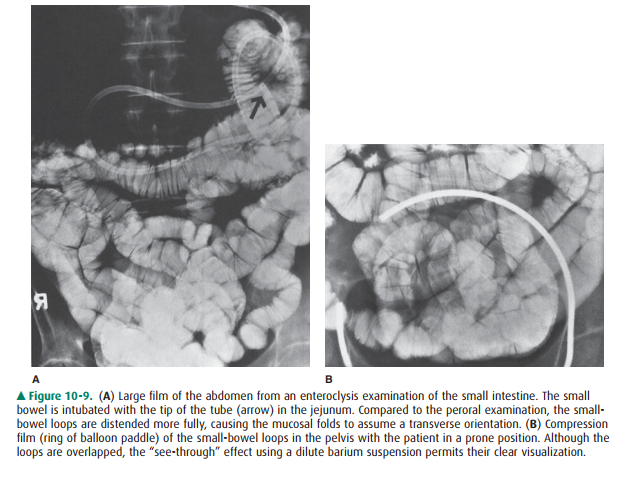

tips and barium suspensions are used for each examination (Figure 10-10). The

single-contrast method simply involves filling the colon with a dilute barium

suspension, whereas the dou-ble-contrast technique requires a denser, more

viscous bar-ium suspension and air. In both methods, large and small

compression images of all segments of the colon are ob-tained. Colonoscopy and

CTC have both had a substantial impact on the numbers of barium enemas now being

per-formed (Figure 10-11).

The large intestine consists of

the rectum, sigmoid colon, descending colon, splenic flexure, transverse colon,

hepatic flexure, ascending colon, and cecum (see Figure 10-10). The length of

the colon varies considerably, mainly because of differences in length and

redundancy of the sigmoid colon and colic flexures. The colon also varies in

caliber depending on location and luminal distention achieved. The mucosal

surface has a smooth appearance, and the colonic contour is indented by the

haustra, which are less numerous in the de-scending colon. The rectal valves of

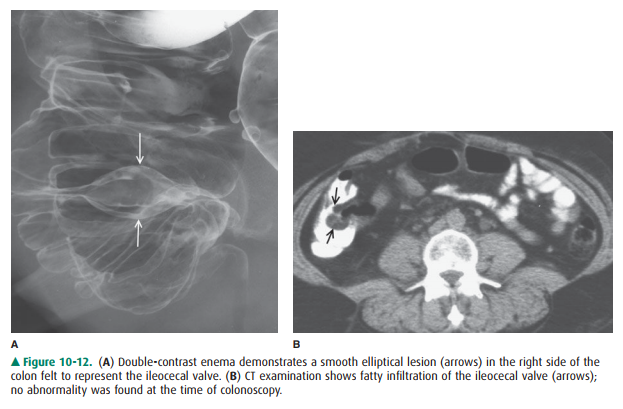

Houston are often seen, especially on double-contrast imaging. The ileocecal

valve has a variety of appearances and may be large if infiltrated by fat

(Figure 10-12).

Related Topics