Chapter: Basic Radiology : Gastrointestinal Tract

Exercise : Colonic Bleeding

EXERCISE 10-5.

COLONIC BLEEDING

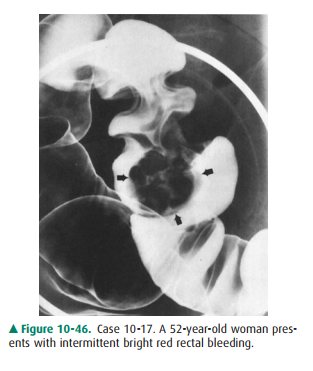

10-17. What is the most likely cause of the large polypoid

le-sion (arrows) in the sigmoid colon in Case 10-17 (Figure 10-46)?

A.

Annular carcinoma

B.

Benign lipoma

C.

Polypoid carcinoma

D.

Pedunculated benign adenoma

E.

Hyperplastic polyp

10-18. What is the etiology of the irregular, focal narrowing in

the ascending colon in Case 10-18 (Figure 10-47)?

A.

Polypoid carcinoma

B.

Annular carcinoma

C.

Inflammatory stricture

D.

Surgical anastomosis

E.

Ischemic stricture

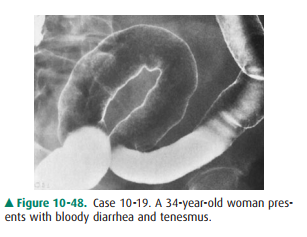

10-19. What is the most likely

explanation of the diffuse rec-tosigmoid mucosal abnormality on double-contrastbarium

enema in Case 10-19 (Figure 10-48)?

A.

Ischemic colitis

B.

Pseudomembranous colitis

C.

Lymphogranuloma venereum

D.

Crohn colitis

E.

Ulcerative colitis

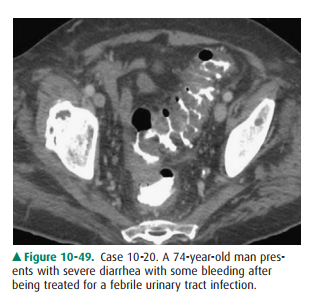

10-20 What is the least

likely cause of the diffuse wall thick-ening of the sigmoid colon seen on the

CT image inCase 10-20 (Figure 10-49)?

A.

Annular carcinoma

B.

Pseudomembranous colitis

C.

Diverticular disease

D.

Crohn colitis

E.

Radiation rectosigmoiditis

Radiologic Findings

10-17. The large, lobulated (ie, irregular surface) polypoid

mass in the sigmoid colon was a polypoid carcinoma (C is the correct answer to

Question 10-17).

10-18. The circumferential, irregular narrowing of the

as-cending colon was an annular carcinoma (B is the correct answer to Question

10-18).

10-19. The diffuse and continuous mucosal granularity seen in

the rectosigmoid colon is most consistentwith ulcerative colitis (E is the

correct answer to Question 10-19).

10-20. The diffuse wall thickening of the sigmoid colon likely

is due to an inflammatory (colitis) disorder or diverticular disease; a

pseudomembranous colitis was the cause in this patient (A is the correct answer

to Question 10-20).

Discussion

Rectal bleeding can result from a

multitude of abnormalities throughout the gastrointestinal tract. In this

exercise, the more important colonic cause of rectal bleeding are illus-trated.

Another common cause of rectal bleeding is divertic-ular disease of the colon,

which is readily shown on barium enema and CT examination. In older patients,

ischemic coli-tis and vascular malformations (eg, angiodysplasia) of the right

side of the colon are increasingly important causes. In general, contrast

studies of the gastrointestinal tract can de-tect many abnormalities that may

be a source of bleeding but cannot determine whether the lesion is bleeding

actively; cross-sectional imaging (with and without vascular contrast

material), nuclear medicine, and angiography can demon-strate active bleeding,

which can also be treated by interven-tional radiology or endoscopy.

The two most common polypoid

lesions of the colon are the hyperplastic and neoplastic polyp. Most

hyperplastic polyps are less than 5 mm in diameter, are sessile and smooth, and

may resemble small neoplastic polyps of similar size. Neoplastic polyps have a

broad pathologic spectrum, which includes: (1) benign adenomas (tubular,

tubulovillous, and villous types); (2) adenomas with focal carcinoma;

andpolypoid carcinoma. Consequently, the radiologic ap-pearances of neoplastic

colonic polyps are varied, and benign and malignant neoplasms may appear

similar. Neoplastic polyps can be sessile or pedunculated and smooth or

lobu-lated (Figure 10-50). Size is an important radiologic criterion to

estimate the risk of malignancy in a sessile colonic polyp; a polyp less than 1

cm in size has only a 1% chance of malig-nancy, with the risk increasing to 10%

for 1- to 2-cm polyps and 25% or more for polyps over 2 cm. The finding of a

pedi-cle is important because invasion of a cancer, if present, to the adjacent

colonic wall is rare. Imaging of the large bowel for colon cancer screening has

changed in recent years, with the barium enema assuming a minor role;

colonoscopy is now most often performed both for detection of neoplastic le-sions

and for their removal, which is possible in most pa-tients. CT colonography may

become more important as a screening modality, but its efficacy is under

intense investiga-tion presently.

Adenocarcinoma of the colon is

the second most com-mon malignancy that affects both sexes. About 95% of

colonic carcinomas occur in patients older than 40 years, with a peak in the

later seventh decade. As with adenocarci-nomas elsewhere in the

gastrointestinal tract, a variety of morphologic forms are seen, including

polypoid carcinoma (malignant potential discussed previously), ulcerative andinfiltrative

types, and the annular carcinoma; the last is also called the “apple-core”

lesion. In the colon of an adult pa-tient, an irregular constricting lesion

having an abrupt tran-sition with the normal colonic wall is nearly always an

adenocarcinoma (Figure 10-51). Inflammatory strictures and surgical anastomosis

typically have a smooth and often tapered appearance.

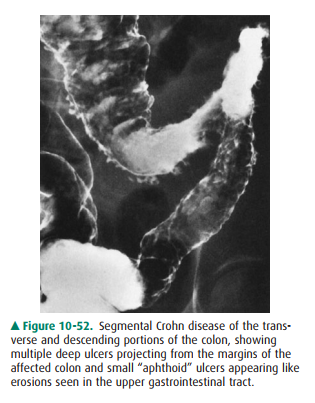

Ulcerative and Crohn colitis are

the two common idio-pathic inflammatory diseases of the colon. Other causes of

colitis include infections of various types, drug-related types (ie,

pseudomembranous colitis), radiation-induced colitis (usually proctitis),

ischemic colitis, and miscella-neous disorders. These other disorders may mimic

idio-pathic colitis, and clinical correlation and exclusion of infection are

important. Radiographic differentiation be-tween ulcerative and Crohn colitis

is usually possible in most patients; of course, cross-sectional imaging, endoscopy,

and pathologic evaluation have important roles. The features most suggestive of

ulcerative colitis are continuous disease with rectal involvement, ahaustral

shortening of the colon, and a finely ulcerated or granular mucosal surface.

The morespecific findings of Crohn colitis include discontinuous dis-ease (ie,

skip areas) with ileitis, eccentric wall involvement, discrete (ie, aphthoid

ulcers) or deep ulceration, intramural fissuring, and formation of fistula to

adjacent organs (Figure 10-52). Complications that may occur in idiopathic

colitis include toxic megacolon, carcinoma, sclerosing cholangitis, and

abnormalities of the eyes, skin, and joints. Toxic megacolon and complicating

carcinoma are more common in ulcerative colitis.

Pseudomembranous colitis has

emerged as a common in-flammatory condition of the large bowel in recent

decades, especially in hospitalized patients. Although a number of risk factors

have been identified, the vast majority of cases are as-sociated with

antibiotic exposure. These drugs alter the intes-tinal flora, resulting in an

overgrowth of Clostridium difficile,

which releases a toxin(s) that produces the inflammatory pseudomembranes and

other pathologic changes. Imaging findings, often best seen on CT examination,

include wall thickening that may be segmental or pancolonic, fold thick-ening

causing an “accordion sign,” and mucosal irregularity due to the

pseudomembranous changes; these abnormalities are often nonspecific, and other

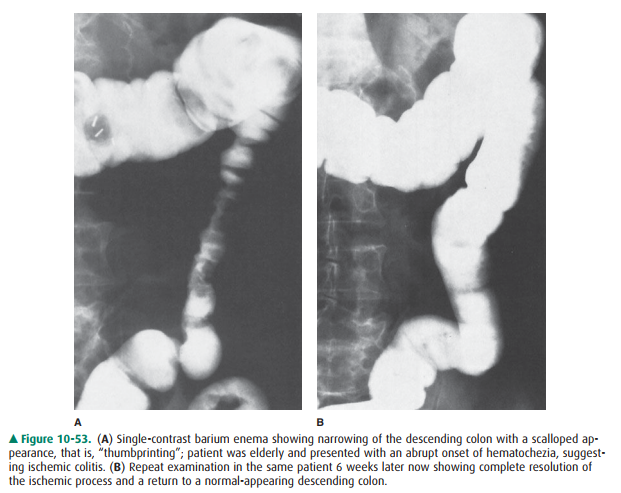

diagnostic tests (eg, sigmoi-doscopy) need to be performed. Ischemic colitis is

common in older patients and warrants further discussion. As in the small

bowel, a variety of vascular changes may cause colonic ischemia. The most

common site of involvement is in the watershed area of the main mesenteric

vessels, that is, the splenic flexure and descending colon, although other

areas and diffuse involvement of the colon may be seen. In the severest form,

colonic infarction and perforation may occur; however, the most common

appearances relate to submu-cosal hemorrhage, which causes narrowing of the

affected colon associated with irregular, smooth margins often called

“thumbprinting”; complete healing and return to normal may occur (Figure

10-53), or progression to a smooth, ta-pered stricture can result.

Related Topics