Chapter: Basic Radiology : Gastrointestinal Tract

Exercise: Dysphagia

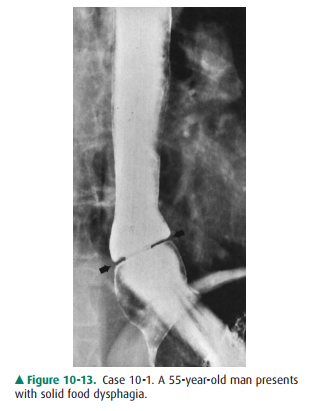

EXERCISE 10-1.

DYSPHAGIA

10-1. What is the most likely cause for the symmetric arrowingat the

lower end of the esophagus in Case 10-1 (Figure 10-13; arrows)?

A.

Carcinoma of the esophagus

B.

Peptic esophageal stricture

C.

Lower esophageal mucosal ring

D.

Achalasia of the esophagus

E.

Esophageal varices.

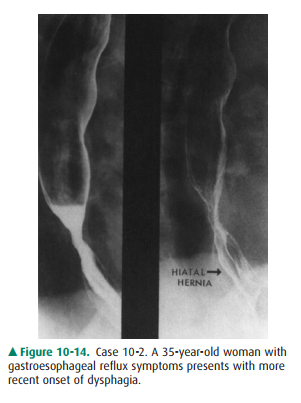

10-2. What is the most likely etiology

of the smooth, tapered narrowing above the hiatal hernia

in Case 10-2 (Figure 10-14)?

A.

Candida esophagitis

B.

Reflux esophagitis

C.

Herpetic esophagitis

D.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) esophagitis

E.

Esophageal malignancy.

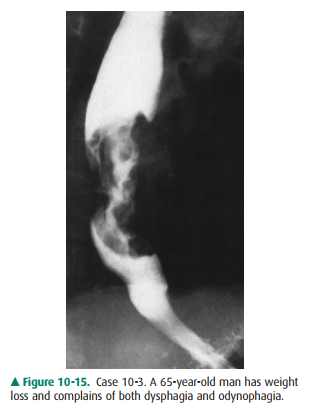

10-3. What is the most likely cause of

the focal, irregular esophageal narrowing shown in

Case 10-3 (Figure 10-15)?

squamous-cell carcinoma (A is the

correct answer to Question 10-3).

A.

Squamous-cell carcinoma

B.

Adenocarcinoma

C.

Stricture from caustic ingestion

D.

Benign peptic stricture

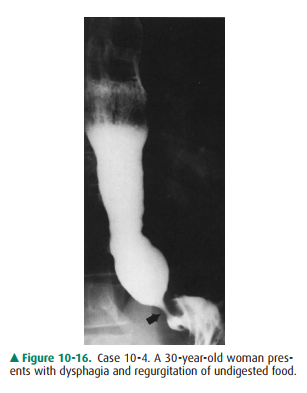

10-4. Esophageal aperistalsis, tapered narrowing at the lower end of the esophagus, and esophageal dilatation are features of

idiopathic achalasia (D is the correct an-swer to Question 10-4).

A.

Stricture from caustic ingestion

B.

Benign peptic stricture

C.

Achalasia of the esophagus

D. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.

Discussion

Dysphagia is a frequent

indication for radiographic or endo-scopic examination of the esophagus. The

most common esophageal causes of dysphagia are shown in the case presen-tations

in this exercise.

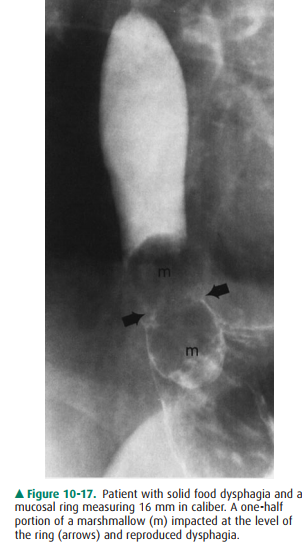

The lower esophageal mucosal ring

is an acquired thin, annular membrane of unknown cause that demarcates the

esophagogastric junction and is a sign of hiatal hernia. More importantly, the

mucosal ring is probably the most common cause of solid food dysphagia seen in

adults (the so-called steakhouse syndrome). Nearly 60 years ago, Schatzki

de-scribed the association of the mucosal ring, which often bears his name,

with dysphagia and determined that the prevalence of dysphagia related to the

caliber of the ring. Rings greater that 20 mm in diameter rarely cause

symp-toms; rings less than 14 mm in caliber are nearly alwayssymptomatic,

whereas mucosal rings 14 to 20 mm in diame-ter cause dysphagia in about half of

patients. The mucosal ring is best detected by radiographic examination, and

the use of a solid bolus, such as a portion of a marshmallow, op-timizes

evaluation of these rings and verifies the structure as a cause of dysphagia

(Figure 10-17).

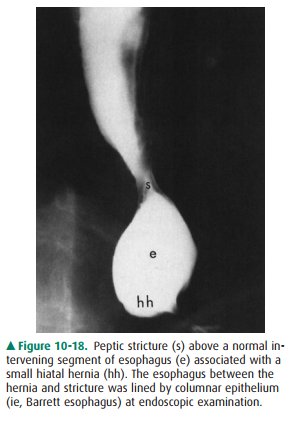

Peptic stricture of the esophagus

is a complication of re-flux esophagitis and is the second most common benign

cause of dysphagia. Reflux strictures typically occur at the esophagogastric

junction and are associated with a hiatal hernia in virtually all patients.

Peptic strictures show a variety of morphologic appearances from a smooth,

tapered nar-rowing to an annular configuration that may resemble a mu-cosal

ring. Irregularity of the stricture margin may also be seen and must be

differentiated from an esophageal malignancy. Barrett esophagus is another

complication of gastroesophageal reflux disease and is suggested when a peptic

stricture is lo-cated above the esophagogastric junction (Figure 10-18);

adenocarcinoma is the most serious complication of Barrett esophagus and has

increased dramatically in recent decades.

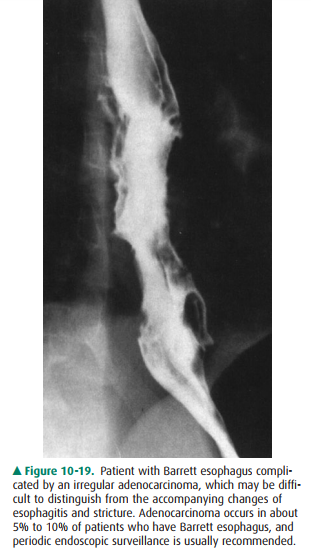

Squamous-cell carcinoma was the

predominant primary malignancy of the esophagus in past decades, but the

escalat-ing increase in adenocarcinoma of the esophagus has had a dramatic

impact on their relative prevalences. The usualappearance of squamous-cell

carcinoma is a focal, irregular narrowing with abrupt upper and lower margins,

which rarely mimics peptic stricture. This esophageal malignancy occurs in

older patients, who often have a history of tobacco and alco-hol abuse;

squamous-cell carcinomas may also be multifocal and associated with similar

lesions in the upper aerodigestive tract. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is

now seen as fre-quently as squamous-cell malignancies and is typically found in

conjunction with Barrett esophagus (Figure 10-19).

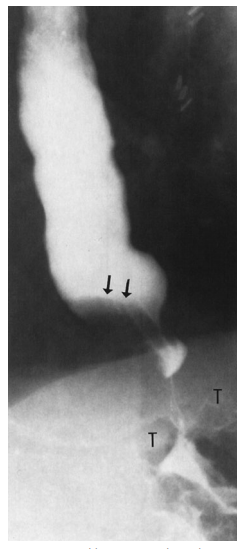

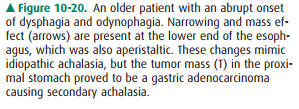

Idiopathic achalasia is a primary

motility disorder of the esophagus of unknown cause that presents with

dysphagia, regurgitation, and weight loss occasionally. The findings on

esophageal manometry include total absence of primary esophageal peristalsis

(aperistalsis), and a dysfunctional lower esophageal sphincter (ie, failure of

relaxation). The radiographic features mirror the manometric findings;

aperi-stalsis is observed and the lower end of the esophagus has a smooth,

tapered or beaklike appearance. In achalasia, hiatal hernia is an uncommon

observation, which is usually seen in patients with peptic stricture or

scleroderma of the esopha-gus. An important differential diagnosis is secondary

achala-sia due to an infiltrative gastric adenocarcinoma (Figure 10-20);

patients are usually older and have a more abrupt onset of symptoms, which

often include odynophagia.

Related Topics