Chapter: Basic Radiology : Liver, Biliary Tract, and Pancreas

Exercise: Pancreatic Neoplasm

EXERCISE 11-6.

PANCREATIC NEOPLASM

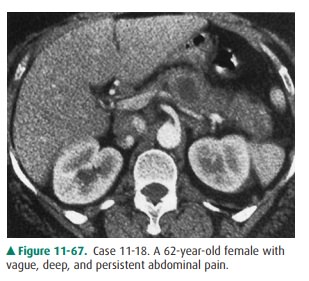

11-18. What is the most likely diagnosis in Case 11-18 (Figure

11-67)?

A.

Pancreatic cyst

B.

Ductal pancreatic carcinoma

C.

Pancreatic metastasis

D.

Peripancreatic lymphadenopathy

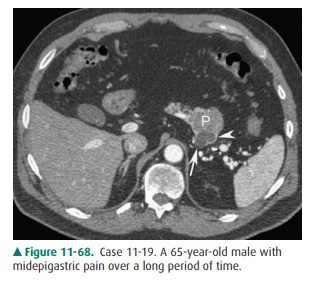

11-19. What is the most likely diagnosis in Case 11-19 (Figure

11-68)?

A.

Cholangiocarcinorna

B.

Cystic pancreatic neoplasm

C.

Ductal pancreatic carcinoma

D.

Pancreatic cyst

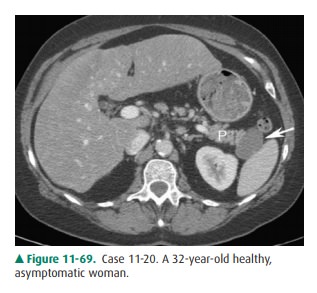

11-20. What is the most likely diagnosis in Case 11-20 (Figure

11-69)?

A.

Acute edematous pancreatitis

B.

Pancreatic pseudocyst

C.

Pancreatic cyst

D.

Cystic pancreatic neoplasm

Radiographic Findings

11-18. In this case, there is a low, but

not fluid, density lesion in the pancreatic body, expanding

the contour of thepancreas, and not associated with any inflammatory changes in

the peripancreatic fat, findings most con-sistent with a ductal adenocarcinoma

(B is the correct answer to Question 11-18).

11-19. In this case, CT demonstrates a fluid density lesion

(arrow) in the tail of the pancreas (P). There is en-hancement along the rim (arrowhead)

that is not as-sociated with surrounding inflammatory change in the

peripancreatic fat. Findings are compatible with a cystic neoplasm of the

pancreas (B is the correct an-swer to Question 11-19).

11-20. In this case, CT demonstrates a unilocular fluid

at-tenuation mass (arrow) in the tail of the pancreas (P) without enhancement

or nodularity. This is difficult to distinguish from a cystic neoplasm;

however, at surgery this was a lymphoepithelial cyst (C is the cor-rect answer

to Question 11-20).

Discussion

Pancreatic masses include tumors,

tumor-like masses such as cysts and developmental anomalies, and inflammatory

le-sions. These can overlap in appearance, as when an inflam-matory mass

simulates a neoplastic mass on imaging studies. They can be causally related,

as when a neoplastic mass sec-ondarily causes an inflammatory mass. Therefore,

differenti-ation among them is not entirely possible, either clinically or

radiographically. However, the prognostic and management implications of the lesions

that create pancreatic masses differ considerably and therefore require

extensive and often invasive investigation. Although contrast studies of the

gastrointesti-nal tract can be used to infer the presence of a mass, usually

cross-sectional imaging studies are employed to establish the diagnosis.

Tumors of the pancreas are

important clinical entities; some have an extremely poor prognosis and some

produce serious clinical symptoms. They can be classified according to origin

as epithelial tumors, endocrine tumors, and mis-cellaneous lesions. Epithelial

tumors can be solid or cystic. Solid ductal adenocarcinoma is the most common

overall and carries the worst prognosis (mean survival 4 months). Cystic tumors

can be divided into cystic lesions arising from the pancreatic parenchymal

cells, such as cystade-noma or cystadenocarcinoma, and those arising from the

pancreatic ductal cells, such as intraductal papillary muci-nous tumors.

Compared to adenocarcinoma, these tumors have a less serious prognosis. Endocrine,

or islet cell, tu-mors elaborate hormonal substances and can create clini-cally

significant symptoms. The two most common of these are insulinoma, which

releases insulin and produces hypoglycemia, and gastrinoma, which releases

gastrin and produces Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. There are many other important

kinds of hormonally active pancreatic en-docrine tumors, and each is designated

by the hormone it secretes (eg, glucagonoma, somatostatinoma). Miscellaneous

lesions arise from pancreatic parenchymal tissue (eg, metas-tases, especially

from melanoma, and lung or breast cancer) or from tissue other than pancreas

(eg, intrapancreatic cholangiocarcinoma or peripancreatic lymph node). These

miscellaneous lesions are important because they sometimes strongly simulate

true pancreatic neoplasms on imaging studies.

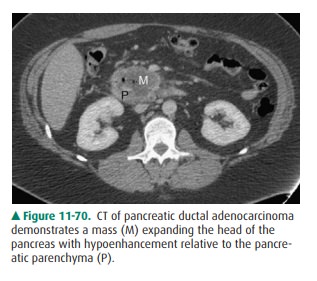

Ductal adenocarcinoma has a

variety of appearances on imaging studies. On US, it usually is seen as a

focal, hypoe-choic, irregular, solid mass. Rarely, it is isoechoic or involves

the entire gland. In some pancreatic head masses, the only finding may be that

the uncinate process is rounded. The pancreatic or biliary duct may be dilated

by the obstructing tumor. Pseudocysts, cystic collections in or around the

pan-creas, may form because of pancreatic duct dilatation and per-foration. On

CT, the tumor presents as a solid, low-density, irregular mass, perhaps with

ductal dilatation, pseudocyst for-mation, or both (Figure 11-67). It usually

enhances to a lesser extent than the surrounding pancreas (Figure 11-70).

Occa-sionally, the tumors will enhance brightly. The pancreas distal to a

ductal adenocarcinoma is often atrophic. Angiography may be used to demonstrate

the vascular anatomy and estab-lish definitively whether certain key vessels

(eg, the superior mesenteric artery or vein) are encased. If so, the lesion is

un-resectable. NM currently has no established role in evalua-tion of

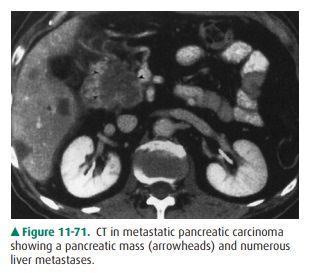

pancreatic tumors. Associated metastases in the liver establish the fact that a

pancreatic mass cannot be simply in-flammatory (Figure 11-71). General

pertinent negatives on cross-sectional imaging may help to differentiate

adenocarci-noma from other nontumorous masses. Calcification is rarely, if

ever, seen in ductal adenocarcinoma, and it is almost never hypervascular.

Ductal adenocarcinoma is

simulated by a number of other entities. These include peripancreatic

lymphadenopa-thy, intrapancreatic cholangiocarcinoma, and pancreatic

metastases.

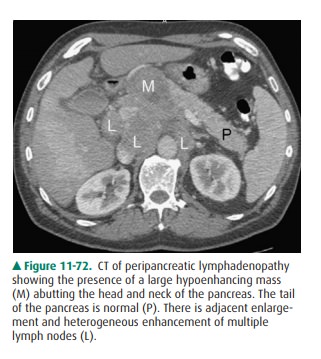

Peripancreatic lymphadenopathy

from lymphoma, leukemia, or any other primary malignancy can closely resem-ble

a pancreatic mass. On imaging studies it may appear as solid soft tissue in the

pancreatic region (Figure 11-72). Keys todifferentiating lymphadenopathy from a

primary solid mass include smooth lobulation and pseudoseptations caused by

in-complete coalescence of the lymph nodes. Also, peripancreatic

lymphadenopathy is much less likely to obstruct the pancreatic duct, although

suprapancreatic lymph nodes obstruct the bil-iary duct as it passes through the

porta hepatis.

Two uncommon neoplastic processes

that occur in the pancreas are cholangiocarcinoma and metastases.

Cholangio-carcinoma usually does not occur within the pancreas, but when it

does, it can exactly mimic a pancreatic head mass to the extent of producing

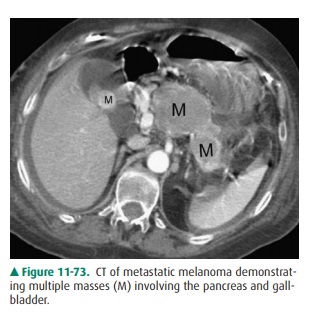

both the pancreatic and common bile duct dilatation. Metastases appear as solid

intrapancreatic le-sions, but with necrosis, they appear as fluid masses.

Because they may be completely indistinguishable from primary tu-mors, the

diagnosis may be inferred only from the clinical his-tory. Pancreatic

metastases are quite uncommon, usually arise from melanoma or lung primary

lesions, and mimic a focal mass lesion of any neoplastic origin (Figure 11-73).

Pancreatic endocrine tumors may

also simulate ductal adenocarcinoma, and in fact, no specific features

consistently distinguish the two. Occasionally, however, certain imaging

features can be helpful, especially when combined with the history. Many islet

cell tumors appear simply as solid masses within the pancreas. However, some

(especially in insuli-noma) may appear hypervascular when studied with fast

bolus or dynamic CT, and they may appear as extremely dense lesions immediately

after enhancement with intravenous con-trast material. Calcifications, which

sometimes are very dense, are more commonly seen with islet-cell tumors. MR

imaging may have a role in the evaluation of islet-cell tumors, because these

tumors have a characteristic appearance on MR studies

Islet-cell tumors and their

metastases have extremely high signal intensity on T2-weighted MR imaging,

which can be used to characterize the origin of the lesion.

Primary cystic pancreatic

malignancies and pancreatic cysts are not readily confused with typical ductal

adenocarci-noma. Currently, cystic pancreatic masses are classified accord-ing

to whether they arise from parenchymal cells or ductal cells. Cystic

malignancies arising from pancreatic parenchymaare classified as either serous

or mucinous cystic neoplasms. This classification is helpful, because the two

lesions are distin-guishable from each other and from solid lesions on imaging

studies. Serous cystadenomas are usually composed of innu-merable very small

cysts (1 mm to 2 cm). Sometimes they con-tain highly vascularized fibrous septa

and a central stellate fibrotic scar, which may calcify. They are generally

benign. Mu-cinous cystic neoplasms are composed of unilocular or multi-locular

cysts larger than 5 cm and may have large papillary excrescences. They are

considered malignant or premalignant lesions. Both serous cystadenomas and

mucinous cystic neo-plasms are cystic, but differences in the typical sizes of

the cysts can be recognized on US or CT. Cystic malignancies arising from

pancreatic ductal epithelial cells are called intraductal papillary mucinous

tumors. These tumors contain consider-able mucus and therefore exhibit complex

appearances on MR imaging. MRCP can be helpful to demonstrate communica-tion

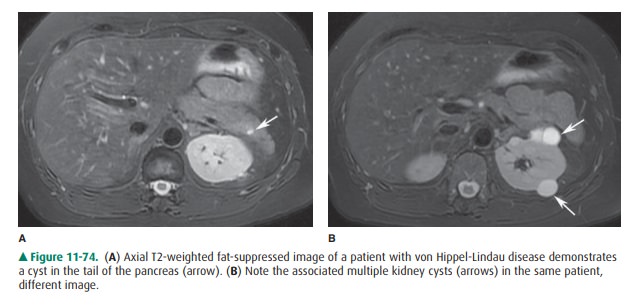

with the pancreatic duct. Pancreatic cysts can occur as iso-lated congenital

cysts or as part of a more generalized multiorgan process that includes adult

polycystic disease or von Hippel-Lindau disease (Figure 11-74). Regardless,

their appearance is similar to that of a cyst in any other organ (Figure

11-69). US and CT depict a uniloculated or multiloc ulated cyst. A pancreatic

cyst can be very difficult to differenti-ate from a mucinous cystic neoplasm.

Management is contro-versial, and they are often followed even when small.

Related Topics