Chapter: Basic Radiology : Liver, Biliary Tract, and Pancreas

Exercise: Biliary Inflammation

EXERCISE 11-4.

BILIARY INFLAMMATION

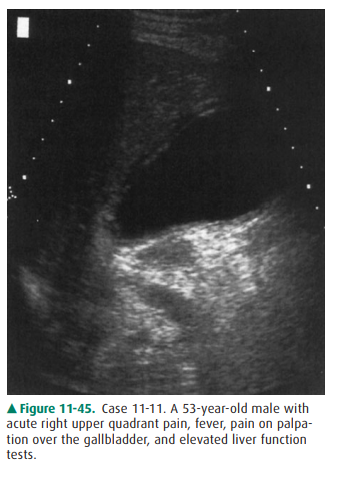

11-11. What is the most likely diagnosis in Case 11-11 (Figure

11-45)?

A.

Acute cholecystitis

B.

Uncomplicated cholelithiasis

C.

Chronic cholecystitis

D.

Porcelain gallbladder

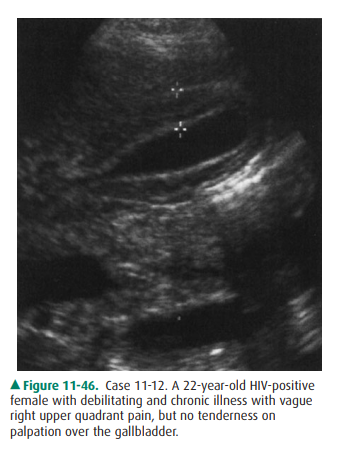

11-12. What is the most likely diagnosis in Case 11-12 (Figure

11-46)?

A.

Oriental cholangiohepatitis

B.

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-associated

cholangiopathy

C.

Choledocholithiasis

D.

Porcelain gallbladder

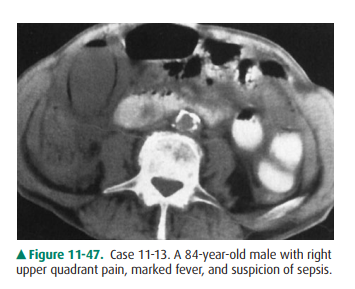

11-13. What is the most likely diagnosis in Case 11-13 (Figure

11-47)?

A.

Acute cholecystitis

B.

Emphysematous cholecystitis

C.

Porcelain gallbladder

D.

Hydrops of gallbladder

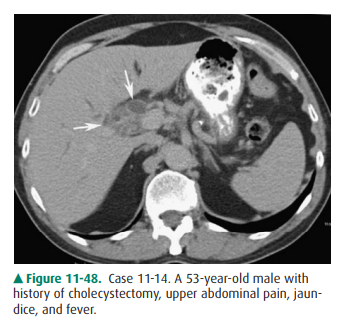

11-14. What is the most likely diagnosis in Case 11-14 (Figure

11-48)?

A.

Choledocholithiasis

B.

Ascending cholangitis

C.

Acute cholecystitis

D.

Emphysematous cholecystitis

Radiographic Findings

11-11. In this case, the gallbladder is distended and the wall

is thickened, measuring more than 5 mm, and has multiple lamina, indicating

gallbladder wall inflam-mation from acute cholecystitis (A is the correct

an-swer to Question 11-11).

11-12. In this case, the gallbladder wall is markedly

thick-ened, measuring over 1 cm, with multiple lamina, but is not tender to

palpation, findings often seen with AIDS cholangiopathy (B is the correct

answer to Question 11-12).

11-13. In this case, gas within the gallbladder wall and lumen

is the primary abnormality, indicating emphy-sematous cholecystitis (B is the

correct answer to Question 11-13).

11-14. In this case, CT demonstrates dilatation of the biliary

ducts with enhancement and thickening of the wall (arrows). In the clinical

setting of fever and jaundice, this most strongly suggests cholangitis (B is

the cor-rect answer to Question 11-14).

Discussion

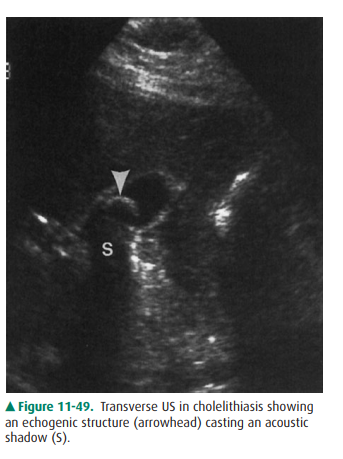

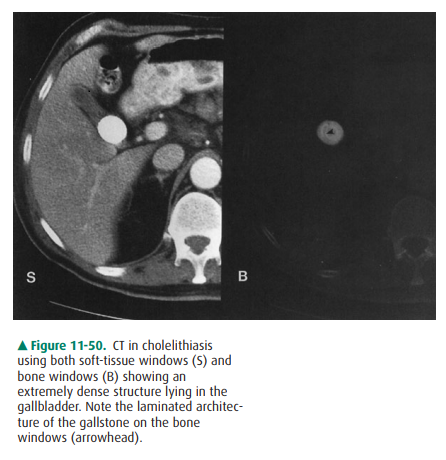

Calculi are a common problem in

the gallbladder and biliary ducts. Cholelithiasis is one of the most common

abdominal disorders overall and is the most common cause of cholecys-titis, as

well as the most common indication for abdominal surgery. Gallstones develop

when the composition of bile, which includes bile salts, lecithin, and cholesterol,

varies from normal and creates supersaturation of cholesterol, which then

precipitates. Historically, patients thought to be harbor-ing gallstones on the

basis of clinical criteria were examined by oral cholecystography, which shows

filling defects in the gallbladder lumen opacified by orally ingested iodinated

con-trast material. However, this examination has been largely re-placed by

sonography, occasionally supported by other imaging information. On US,

gallstones usually appear as mobile, intraluminal, echogenic foci that cast a

well-defined acoustic shadow (Figure 11-49). Two other possible appear-ances

are echogenic foci in the gallbladder fossa without visi-ble surrounding bile

when the gallbladder is contracted, and small, mobile, echogenic foci that do

not cast a shadow. On CT, gallstones appear as dense, well-defined,

intraluminal structures (Figure 11-50), but their density can vary from fat

density to near bone density, depending on the relative con-centration of

calcium and cholesterol. Because of their vary-ing density, they can sometimes

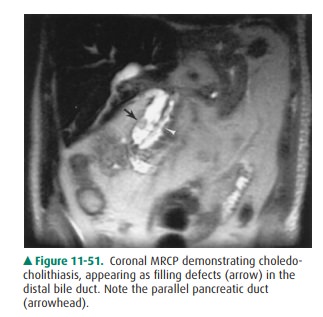

be difficult to see on CT. MR imaging of the biliary system, especially MRCP,

has become more important in biliary imaging, including the detection of

calculi of the gallbladder and biliary tree. Although US re-mains the primary

and initial means of identifying biliary calculi, MRCP can be used as a

supplementary technique, es-pecially in ductal calculi, because imaging of the

biliary treeby US may be suboptimal when obscured by bowel gas. MRCP can depict

the biliary system, filling defects within the biliary tree (Figure 11-51), and

congenital variants of the biliary ducts and is about as accurate as ERCP in

displaying a biliary “road map.” It can also be used to evaluate the biliary

ducts when ERCP is impossible to perform, such as when the patient has

undergone a Billroth procedure, interrupting the continuity of the upper

gastrointestinal tract. NM and angiography have no major role at this time in

assessment of gallstones.

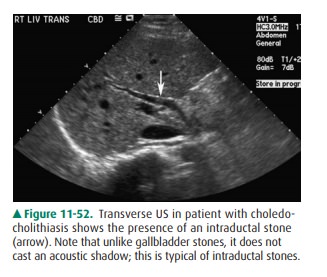

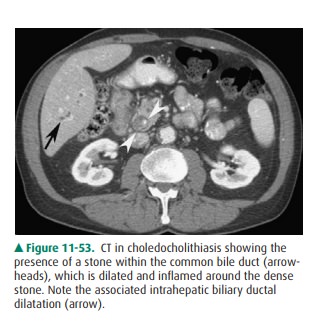

Choledocholithiasis occurs when

calculi pass from the gallbladder into the biliary ducts or when calculi

develop originally within the ductal system. Regardless of origin, they may

obstruct the biliary ducts, cause biliary colic, and lead to cholangitis.

Common duct stones can be evaluated with US, CT, and MRI, or by direct

visualization with ERCP. On US, choledocholithiasis appears as echogenic foci

within the lumen of the biliary duct. Sonographically, common duct stones are

detected less readily than gallbladder stones, and meticulous technique is

required. The entire course of the common bile duct may be technically

difficult or impossible to follow. Choledocholithiasis can cause acoustic

shadows, but for technical reasons these stones are detected less fre-quently

than cholelithiasis (Figure 11-52). On CT, choledo-cholithiasis appears as

intraluminal biliary ductal foci, which, like gallbladder stones, may vary in

density from hypodense to isodense to hyperdense to bile, depending on their

compo-sition (Figure 11-53). On MRCP, choledocholithiasis is seen as a filling

defect in the duct.

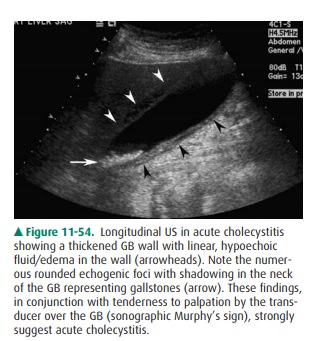

Cholecystitis is inflammation of

the gallbladder that is al-most always caused by obstruction of the cystic

duct, usually by an impacted calculus. The inflammation may be acute orchronic,

uncomplicated or complicated, calculous or acalcu-lous. As the gallbladder

continues to accumulate bile, intralu-minal pressure increases and vascular

insufficiency of the wall occurs, causing ischemia, necrosis, and often

superven-ing inflammation. The gallbladder distends, the gallbladder wall

thickens from edema, and the patient is tender to palpa-tion over the

gallbladder (positive Murphy’s sign).

Both ultrasound and hepatobiliary

NM studies are the modalities of choice to evaluate possible cholecystitis.

Sono-graphic signs of acute cholecystitis include cholelithiasis, gallbladder

wall thickening (greater than 3 mm), irregular orlinear hypoechoic structures

within the gallbladder wall, a positive sonographic Murphy’s sign, and marked

gallbladder distention (Figure 11-54). A combination of these signs is a good

positive predictor of acute cholecystitis. In marked chronic cholecystitis, US

shows persistent gallbladder wall thickening or sludge, stones, and contraction

of the gallblad-der. However, in the presence of cholelithiasis, the

gallbladder almost always shows signs of chronic inflammation histolog-ically,

even without symptoms or sonographic findings.

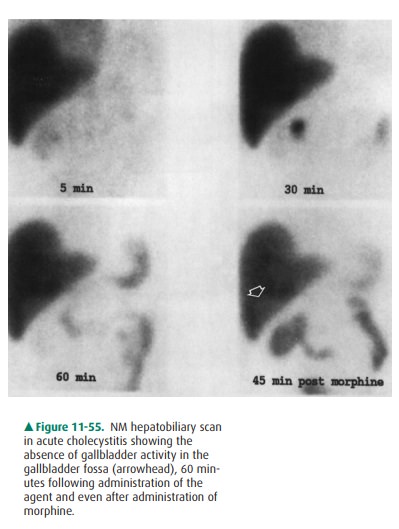

Hepatobiliary NM HIDA scans

depict acute cholecystitis as an absence of filling of the gallbladder with the

radionu-clide once it is excreted by the liver into the biliary ducts; this

absence of filling is due to the obstruction of the cystic duct lumen by

inflammatory edema of the cystic duct wall (Figure 11-55). Sufficient time must

be given to fill the gallbladder. This time interval depends upon whether or

not morphine is administered. Morphine increases the tone of the sphincter of

Oddi and increases intraluminal common bile duct pressure to overcome the

resistance to bile flow into the gallbladder in chronic cholecystitis, but not

in acute cholecystitis when a stone obstructs the duct. Acute cholecystitis is

diagnosed when absence of activity is noted either 45 minutes after morphine

augmentation or after 4 hours without morphineaugmentation. Delayed gallbladder

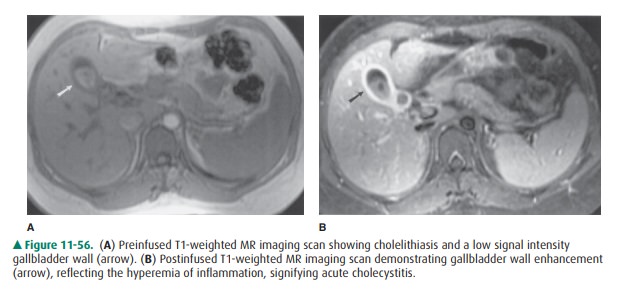

visualization after 1 hour usually reflects chronic cholecystitis. On CT, the

morphologic findings in patients with acute cholecystitis are similar to the US

findings, including gallstones and thickened and inhomo-geneous gallbladder

wall. However, CT is not as sensitive as US or NM either to the presence of

gallstones or to acute cholecystitis. MR imaging can depict the presence of

gallblad-der wall inflammation in the absence of wall thickening by

demonstrating wall enhancement following Gd infusion (Figure 11-56). The exact

role of MR imaging in cholecystitis has not yet been completely evaluated.

Angiography has no role in the diagnosis of cholecystitis.

Many potential complications and

conditions are associated with cholecystitis. These include hydrops, porcelain

gallbladder, milk-of-calcium bile, and emphysematous cholecystitis.

Hydrops refers to the marked

distention of the gallblad-der by clear, sterile mucus, usually under

conditions of chronic, complete cystic duct obstruction. On imaging stud-ies,

the primary finding is enlargement of the gallbladder (Figure 11-57).

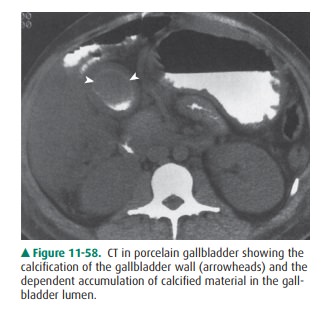

Porcelain gallbladder refers to

calcification of the gall-bladder wall, as a result of chronic inflammation

causing dystrophic calcification and often associated with recur-rent acute

cholecystitis. Gallbladder stones are usually present, and there is a higher

incidence (approximately 10% to 20%) of gallbladder carcinoma. On imaging

stud-ies, complete or incomplete circular wall calcification is present and is

seen as a curvilinear, highly echogenic wall on US or as a curvilinear,

high-attenuation wall on CT (Figure 11-58).

Milk-of-calcium bile refers to a

precipitation of calci-fied material within the lumen of the gallbladder,

usually associated with chronic cholecystitis. US shows echogenic sludgelike

material, possibly with gallstones. CT demon-strates the distinctive appearance

of a horizontal bile-calcium level.

Emphysematous cholecystitis is a

distinctive condition and should be treated as a medical/surgical emergency.

Like acute cholecystitis, it is marked by intense gallbladder wall

in-flammation, but unlike acute cholecystitis, it is not necessar-ily

associated with gallstones. It may be related to ischemia of the gallbladder

wall from small-vessel disease, and it affects an older age group than does

acute cholecystitis. The most common group affected is older diabetic men. Gas

is released by bacterial invasion and accumulates in the gallbladder wall,

lumen, or both. On US, gas is seen as an echogenic focus pro-ducing poorly

defined or “dirty” shadowing behind it. The wall is thickened, perhaps focally,

with gas. On CT, air-density gas is seen within the lumen or wall (Figure

11-47). MR imagingand angiography have no current role in evaluation of these

complications.

Like inflammation of the

gallbladder, inflammation of the biliary ducts, or cholangitis, is an important

clinical con-dition. It is less common than cholecystitis. AIDS-associated

cholangiopathy, ascending cholangitis, and oriental cholan-giohepatitis are three

important forms of cholangitis.

AIDS-associated cholangiopathy is

marked by the fre-quent isolation of opportunistic organisms, including Cryp-tosporidium and cytomegalovirus

from the bile, and by considerable

inflammation of the bile duct wall. On US or CT, the gallbladder or biliary

duct walls may be markedly thickened (greater than 4 mm) (Figure 11-46) and may

contain irregular lamina. Inflammation is present, but stones may or may not be

present. Cholangiography shows irregular stric-tures, papillary stenosis, or

both.

Ascending cholangitis is a

bacterial inflammation of both walls and lumina of the biliary system,

including the gallbladder. It is almost always due to obstruction of the

biliary tract, especially when caused by choledocholithiasis and distal

bile-duct stenosis. The presence of grossly puru-lent material within the duct

indicates suppurative cholan-gitis. Cross-sectional imaging studies are used to

define the level and cause of obstruction. Cholangiography can show the

abnormal biliary ducts directly. The purulent material of suppurative

cholangitis may be seen as echogenic mate-rial on US, high-density material on

CT, or filling defects on cholangiography.

Oriental cholangiohepatitis is a

common illness in en-demic areas of Asia and can be seen in Asian immigrants in

this country. It may be caused by bile duct wall injury from the parasitic

infestation. Ductal stones commonly form, and the ducts are dilated. A

characteristic finding is the presence of intraductal (especially intrahepatic

ductal) cal-culi. These findings are readily demonstrated with US, CT, and

cholangiography.

Related Topics